When the world’s eyes turn to Maracanã Stadium on Friday, the International Olympic Committee hopes the opening ceremony will launch a redemption story. But even if the Rio Games defy the skeptics, their troubles are already driving calls for changes to the Olympics’ site-selection process.

For the second consecutive Olympics, a city’s basic capacity to deliver the multibillion-dollar festival is in doubt. The Olympics’ brand has been dragged down by the drumbeat of economic, political and security calamities.

Sponsors, teams and organizers have been consumed by crisis management instead of promoting sport — like the Australian team’s sudden shift to a hotel when it discovered unfinished plumbing and exposed wires in the Olympic Village last week.

|

Work continued last week on Olympic Park.

Photo by: Getty Images |

“You should now have to prove financial wherewithal,” said Rich Bender, executive director of USA Wrestling and chairman of the U.S. National Governing Body Council. “These Games have grown to the size and scale where you can’t just assume that once you give them the Olympics it’s all going to get figured out.”

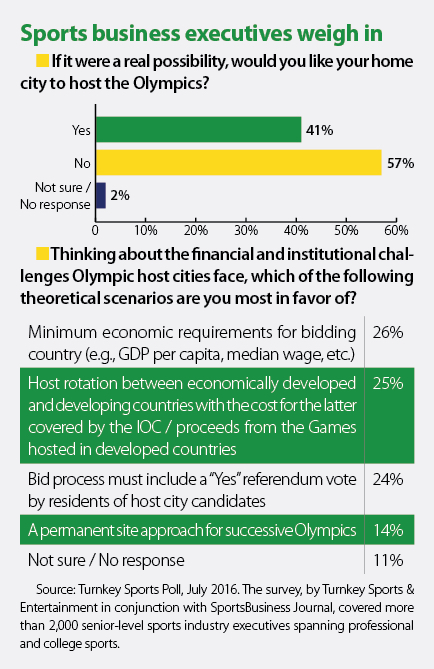

Some in the Olympic movement hope Rio marks the tipping point toward a fundamental recalculation of how hosts are chosen, believing it’s crucial to emphasize risk reduction and predictability over idealism and globalism. Others even raise the prospect of a strategic rotation among the small group of proven, willing hosts such as London, Los Angeles and Beijing.

Such a radical change would run into powerful headwinds among Olympic traditionalists, who believe the Games must serve a truly worldwide constituency and not just wealthy, developed nations. It also would undercut individual IOC members’ power and influence, though it could give sponsors a new measure of certainty.

IOC members say they already changed the bid process to emphasize prudence and sustainability in the Agenda 2020 reform packages pushed by President Thomas Bach shortly after his 2013 election. But leaders of sports groups say Rio’s problems make it clear that high costs and high uncertainty are hurting the movement.

“I believe it is important that when choosing future Olympic cities, the IOC needs to ensure that the infrastructure necessary to host the largest event in the world is assured,” said USA Gymnastics President Steve Penny. “And that all of the stakeholders have a good chance of participating with a high degree of confidence and stability.”

Capabilities questioned

For decades, cities have pursued the Olympics as a way of proving themselves worthy of the world stage. The IOC encourages that perspective to build demand and gain leverage to dictate terms. Indeed, Rio beat out Chicago, Madrid and Tokyo in 2009 because IOC voters thought it was important to bring the Games to South America for the first time, not because it was the safest choice.

Since then, the Russian government spent $50 billion to create a winter sports resort from scratch at Sochi, delivered hotels late and now has white elephant facilities. Then, the bottom fell out of the Brazilian economy after oil prices plummeted, stressing the public sector and Rio 2016’s budget to the point of breaking.

The Games will go on, but the city’s water pollution won’t be cleaned up as promised,

favelas won’t be improved as promised, and only a last-gasp, costly push will keep the $2.8 billion subway expansion opening as promised. All in all, Rio looks to be on the hook for about a 50 percent cost overrun compared to its original plans, even after its organizing committee cut its own budget by 30 percent.

The federal Brazil government had to deliver nearly $900 million in emergency aid to the state of Rio de Janeiro to cover its final costs while police, firefighters and hospitals clamor for money themselves. Brazilians have soured on the Games, according to recent polls, undercutting even the theory that host cities enjoy a boost to civic pride.

All of this raises an unpleasant question for the Olympics: At a time of increasing political and economic instability, how many places in the world are really up to the task of hosting, much less willing? And when the scale of the Games requires a vote seven years in advance, how many places can promise bankable stability? The growing concerns over terrorism further raise the stakes.

“The scale of the Games right now is at a point where the security requirements may be outstripping the capabilities of all but a handful of nations,” said Dave Mingey, founding partner of GlideSlope, a firm that advises Olympic sponsors such as Procter & Gamble, McDonald’s and Citi on global sports sponsorships.

But there’s virtue in taking the Olympics to new places like Rio, said Angela Ruggiero, an American IOC member.

“The IOC selected Rio for an opportunity to go to a part of the world that has never seen an Olympic Games on its soil,” she said. “We shouldn’t forget that, because the Games will now have an opportunity to reach a larger audience in a part of the world that’s never had them before.”

Business likes new markets, too. Brazil, China and Russia were the darlings of the world economy at one time, and therefore especially desirable to Olympic partners.

Patrick Baumann, a Swiss IOC member and secretary general of the International Basketball Federation, rejects the notion that only certain places should have the Games. “At some point, it is absolutely correct and fair for the Olympic movements to have the Games in Africa,” he said. “The Olympics is about the whole world, and it’s not just about some countries and some cities only.”

However, Ruggiero acknowledges there’s a cost-benefit analysis that must be conducted in places like Rio, balancing the upside of the first South American Games with the costly challenges. “There are struggles embedded in every Games, but hopefully, the long-term benefits will be worth the result,” she said. (Academic researchers such as Smith College’s Andrew Zimbalist have found no lasting economic benefits to host cities, and only a fleeting morale boost.)

Changes already made

Bach’s signature Agenda 2020 reform package approved in December 2014 does a few things to encourage affordability and risk reductions.

Now, the IOC involves experienced staff in the early phases of bidding, permitting a consultative relationship between IOC staff and candidate cities instead of the RFP-style bidding of the past. Cities are encouraged to re-use existing venues and consider “sustainability” in all phases of their bids.

|

Crews were also finishing last-minute work at the Olympic Village.

Photo by: Getty Images |

The cities vying for the 2024 Summer Games clearly see risk reduction as a major selling point. Los Angeles, Paris, Budapest and Rome all try to paint their bids as less reliant on new infrastructure or uncertain political outcomes.

Gene Sykes, a Goldman Sachs partner and CEO of LA 2024, said it will be good for the Olympic movement if future Games can be hosted with less struggle, and Los Angeles is eager to show the way. Earlier this year, with guidance from the IOC, L.A. scrapped plans for a multibillion-dollar mixed-use real estate development as an athletes village in favor of using UCLA residence halls slated for upgrades.

“If we can make it a great Olympic Games with our own resources, without having to invest in everything new, and without having to take the risk of development with something like that, it will be a great step for the Olympic Games, and we’re very consistent with that direction,” Sykes said.

But Agenda 2020 has its limits. It directs IOC staff and its subsidiary bodies, but it imposes no particular requirements on the roughly 100 voting IOC members who actually decide, in secret ballots, where the Games go.

“I hope they begin to look at it more strategically as opposed to letting members vote on it, but it’s kind of a birthright for those members,” said a senior U.S. official with a history of bidding for the Games. “What the IOC would do if it were a private organization is go to Paris and L.A., and say, ‘We need you both. L.A., why don’t you take ’24 because you’re a little closer to ready, and Paris, take ’28,’ and then submit it to members.”

Skeptics were not encouraged in July 2015, when the body narrowly awarded the 2022 Winter Games to snowless

|

Students walk home from school in a favela overlooking Maracanã Stadium.

Photo by: Getty Images |

Beijing — which will require a $1 billion train line to connect the crowded city to a mountain resort and historic amounts of manufactured snow — over Almaty, Kazakhstan, an admittedly remote but bona fide winter sports resort.

Speaking privately at the time, skeptics said it was proof that the old ways of rewarding friends won out over the technically superior, prudent choice.

The membership universally supported the reforms, Ruggiero said, a strong indication that membership will keep those efforts in mind when they vote. But speaking privately, other members say Agenda 2020 is sufficiently broad to lead a member to any decision he or she wants. Ruggiero admits not everyone values risk reduction the same way.

“Some might see it that way, others might see the universality principle — that it’s a risk worth taking again to deliver the Games somewhere that otherwise might not have the opportunity,” she said.

It would require an overhaul of the Olympic charter to create a rotation.

The cost of risk and crisis

It’s true that some of what appears from afar to be a crisis in Rio is just media sensationalism. It’s also true that the Games have a way of working out. But threats, uncertainty and risk have real costs to sponsors and participants.

The USOC has had to call in medical experts, answer questions from politicians, and reassure athletes and teams that they’re on top of security and health worries. Last week, many Olympic teams arrived to find their accommodations at the Olympic Village incomplete.

Sponsors have had to assess risks, reconsider activation plans and, in some cases, add security as conditions deteriorate in Rio.

Olympic partners tend to be sophisticated corporations that are mostly taking the Rio challenges in stride,

GlideSlope’s Mingey said, but they won’t be so sanguine if the challenges of Rio become regular parts of the Olympic business.

“I think much of the discussion isn’t about Rio 2016 but more about the broader Olympic movement and what we can all do to try to ensure these types of situations remain firmly in the past [after Rio],” Mingey said.

The next two Olympic hosts, Pyeongchang, South Korea, and Tokyo, are showing some warning signs. Their respective national economies appear more or less sound, but Pyeongchang recently asked the IOC and the South Korean government for more money to cover skyrocketing costs, and Tokyo had to cut $1 billion from its original stadium design amid public outcry.

Mingey said a British Open-style rotation might not be as controversial as it would seem, and a fixed entity might even sell better with sponsors, weary after Rio.

“My guess is, I don’t think history would reveal the world to be that upset if a handful of cities rotated through a cycle for both the summer and winter Games,” Mingey said.

Much of what’s plagued Rio isn’t necessarily the fault of the Rio organizing committee or the IOC. The core problems facing Rio tie back to the profound recession, which was hard to imagine in 2009, when Brazil was flying high on oil prices and bounced back rapidly from the worldwide recession.

“The economic crisis, you simply can’t predict,” said Baumann, the Swiss IOC member. He defended the Rio choice as “absolutely” the right decision. “It’s seven years ahead. It’s very hard to use these elements to be fully secure in whatever you’re going to do,” he said.

That long run-up to the Games is necessary because of the sheer scope of the event, but only adds to the dilemma. Places that are rich and stable enough to entertain a bid now, and also are able to guarantee they’ll remain so nearly a decade later, are few and far between.

Longtime American IOC member Anita DeFrantz believes in the system and disputes the notion that Sochi or Rio were mistakes. She expects the Rio Games to go off without many problems, and thinks the IOC staff and future host cities will continue to learn how to work together to deliver the product under Agenda 2020’s reforms.

“Let me put it this way: We haven’t made a mistake yet,” she said, “and I don’t think we will.”