|

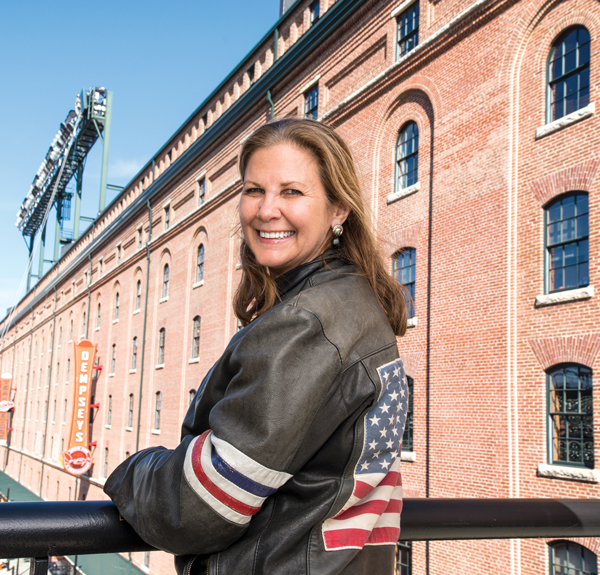

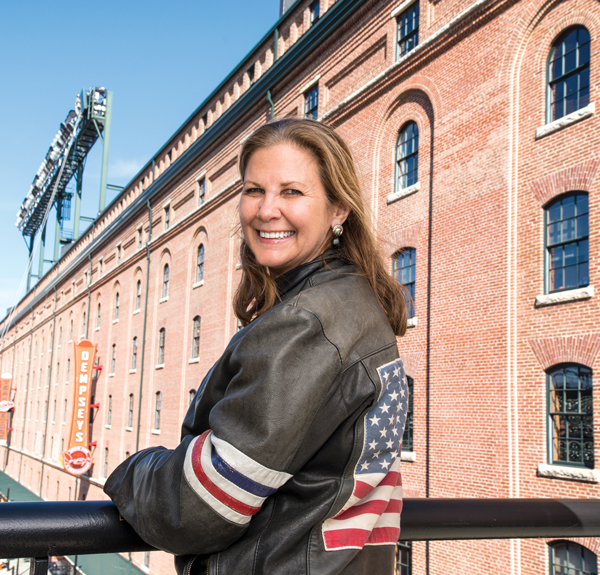

Janet Marie Smith stands in front of the B&O Warehouse overlooking Eutaw Street at Baltimore’s Camden Yards, the first of several of her projects that have shaped the modern-day sports facility.

Photo by: HARRY CONNOLLY

|

Visiting an old friend’s office in the converted warehouse beyond the right-field fence at Camden Yards, Janet Marie Smith tapped the screen of her phone, opening a menu of photos as she showed off her latest project.

“Looks like I’ve got 1,083 pictures,” said Smith, the architect and urban planner who launched her sports career working on the revolutionary, and now iconic, Baltimore ballpark. “How much time do you have?”

His arm in a sling after shoulder surgery, sports banker John Moag tried to contain a belly laugh. As Smith flipped through shots of the Dominican Republic training academy that she overhauled for the Los Angeles Dodgers, for whom she now serves as senior vice president of planning and development, Moag glanced up over his reading glasses.

THE CHAMPIONS

This is the fourth installment in the series of profiles of the 2017 class of The Champions: Pioneers & Innovators in Sports Business. This year’s honorees and the issues in which they were featured are:

■ Feb. 6: Larry Levy

■ Feb. 20: DeLoss Dodds

■ March 6: Ed Goren

■ March 20: Janet Marie Smith

■ March 27: George Raveling

■ April 3: Bill Giles

“This is like me with my grandchildren,” chuckled Moag, the former chair of the Maryland Stadium authority.

“Well,” Smith replied, “these are my babies.”

The Campo Las Palmas project, which modernized and vastly expanded the facility in which the Dodgers train, house, educate and assimilate teenage players from across Latin America, is the latest in Smith’s sports facility brood. Before that came a $100 million renovation of Dodger Stadium, which included a field-level excavation and the construction of seven buildings that added badly needed concessions and shops. Before that, she saw the Orioles through a $21 million update of Camden Yards and $31 million makeover of the Orioles’ spring training complex in Sarasota.

All of those were preceded by three projects that each changed sports architecture in its own way:

■ The against-all-odds renovation of Fenway Park, given up for dead by its previous owners.

■ The conversion of Centennial Olympic Stadium into Turner Field, followed by the construction of Philips Arena, both in downtown Atlanta.

■ The dawning of Camden Yards, which Smith shepherded from conception through completion, a project that altered both what teams built and where they built it.

That she came to sports at all was a happy accident, the well-timed meeting of a just-hit-30 architect drawn to the complexities of large, heavily used spaces and a headstrong baseball executive who wanted to reverse the course of the previous three decades of sports facilities by building an old-timey ballpark downtown.

“I like to think I was able to recognize her energy and talent and zeal and passion, even though she had a very untraditional baseball background,” said Larry Lucchino, who hired Smith as vice president of planning when he was president of the Orioles, and then again when he led the Red Sox. “But what I thought I saw early on proved to be true in spades. Her artistic sensibilities, but also her energy and interpersonal skills and the passion she brought to her work — those all set her apart.

“She loved the buildings she worked on. This is a woman who loved Camden Yards. She loved Fenway Park. Really loved them. And she was not afraid to articulate those feelings for these brick-and-mortar creations.”

■ ■ ■ ■

Over lunch at a brew pub created during the latest Camden Yards renovations, Smith thought back to her first visit to the spot. It was 1989, and the B&O Warehouse was just that, a 1,116-foot-long, eight-story-high stretch of brick and glass that stood vacant, a reminder of an industrial Baltimore that had shipped out.

There was intense debate over whether the structure would be incorporated into the publicly funded ballpark that the Orioles were building on the site. Some suggested a portion of it might be saved. The most ardent opponents wanted to bulldoze it entirely.

The daughter of a Jackson, Miss., architect who took his family to visit old post offices while on vacation, Smith typically preferred preservation to demolition. She badly wanted to incorporate the warehouse — and as more than a decorative prop.

In search of a solution, Smith asked a developer friend who rehabbed a string of Baltimore mill buildings to show them how he had used exposed duct work to cope with the low ceilings, a practice rarely seen at the time. Doing so would allow them to use all eight floors of the building. Smith then convinced concessionaire Aramark to move its main kitchen and service level from the ground floor, giving it over to a restaurant, a team store and ticket offices.

And so, with the block-long warehouse creating a pedestrian thoroughfare that could be gated off during games, the now famed Eutaw Street was born.

“The thing about the warehouse: It’s real,” Smith said, extending both hands to make the point. “That’s one thing I love about having it here. It gave us a reference point that dictated virtually everything else — from the field dimension to the vertical scale of the building to the brick and the steel palate and the seat colors. … The warehouse, more than anything, was like our clue of what to do.”

|

Smith speaks during a 2004 news conference with Boston Red Sox President and CEO Larry Lucchino (right) and Fenway Park groundskeeper Dave Mallor.

Photo by: AP IMAGES

|

Those who know the story best like to refer to the ballpark’s origin as the perfect convergence of people, circumstance and time. There was Lucchino, the team president, who wanted an old-style baseball park with modern amenities. There was Maryland governor and former Baltimore mayor William Donald Schaefer, who wanted to attract visitors and development to the city’s blighted inner harbor. There was a city and a fan base that had lost its NFL team, and thus was more willing than most to break the mold and fund a stadium that would host only one tenant.

And there was Smith, hired to oversee the project on behalf of the Orioles even though she’d never worked in sports.

The stage for Smith’s unlikely veer into baseball was set not long after she entered the work force. After graduating from Mississippi State with her architecture degree, she set off for New York, attracted by the fervor of a large city. Her first job was a plum, a coordinator’s role on the vast Battery Park City project in lower Manhattan. Raised around architecture, she knew that she didn’t want to spend her career designing one house or building at a time. So she enrolled in graduate school at CCNY, where she studied urban planning.

“You know how in fifth-grade science class you dissect a frog? Well, in graduate school you dissect a city,” Smith said. “I picked Baltimore as my city.”

Smith was in her next job as planner of another large urban project, Pershing Square in Los Angeles, when she learned that the Orioles intended to leave Memorial Stadium for a downtown site. At first, she was disappointed. She had visited Memorial while studying Baltimore and thought it a “great, old-shoe ballpark.” About six weeks later, she changed her mind.

“It was Thanksgiving Day and I was sitting in Mississippi at my mother’s dining room table and I just got this eureka moment,” Smith said. “I thought, that could be cool. If they approach it as part of the urban renaissance, that could be pretty cool.”

The Orioles were considering hiring an in-house architect to represent them during design and construction, so Smith sent a résumé. It got no farther than the team’s longtime HR director who, seeing a 30-year-old urban planner with no experience in sports or obvious connection to Baltimore, dropped it into his “kiss-off” file, along with the many others sent along by dreamers who presented no clear qualifications.

Fortunately for Smith, Lucchino insisted on reviewing the “kiss-off” file before rejection letters were sent. When he came upon Smith’s résumé, he rescued it.

“This is a woman who is an architect with a master’s degree in urban planning,” Lucchino told the HR director. “Don’t you think that’s the sort of person we ought to be talking to?”

|

Incorporating the warehouse as a guiding point helped determine everything from Camden’s field dimension, vertical scale and even its color palate.

Photo by: HARRY CONNOLLY

|

Lucchino was intrigued, but not yet sold. When Smith interviewed, he began with a question that sounded more like a challenge.

“Which league has the designated hitter?” Lucchino asked, stone faced.

“I’m offended by the question,” Smith said.

“Oh, good,” Lucchino said. “Sit down. Let’s talk.”

As they got to know each other, Lucchino was struck by Smith’s mix of charm and spunk, as well as her knowledge of baseball. They quickly built a rapport. Lucchino laid out a master plan for development around Camden Yards as well as a set of early ballpark plans by HOK. He asked her what she thought of them.

“They hadn’t yet jibed,” Smith said, recalling the preliminary drawings that seemed to miss Lucchino’s vision of an asymmetrical, old-style ballpark that took cues from its surroundings. “The master plan spoke directly to what he wanted. We needed to spend time on the architecture to fit the goals outlined in the master plan.

“Larry’s questions to me during that interview gave me a chance to react to what he had in front of him. So we both had a chance to see if it was a fit. I’d never worked on any sports things. So if what they wanted was someone who could draw the traditional sports conclusion, it wouldn’t have been the right fit.”

Smith brought Lucchino and Orioles owner Eli Jacobs what they needed — not another hand to draw lines, but an eye to interpret their vision and a voice to convey it.

“There’s an old Mies van der Rohe line: God is in the detail,” Lucchino said, quoting the pioneering architect of the mid 20th century. “That’s one of the things she brought. She took a general concept — maybe the one and only original idea I’ve ever had about ballparks, a traditional old-fashioned park with modern amenities — and she gave life and meaning to that concept in 100 different ways.”

■ ■ ■ ■

While catching up with Moag, Smith was in Baltimore on a Monday in February — the busy season for those who build and overhaul baseball parks — as she typically has been on Mondays and Fridays throughout her sports career, even while holding senior positions with franchises in Atlanta, Boston and now L.A.

It’s a work style she adopted late in her stint in Baltimore, when Camden Yards was up and running and the Atlanta Braves were planning the complicated conversion of the Olympic track and field stadium into a workable major league ballpark. Stan Kasten, then president of the Braves and Atlanta Hawks, approached his friend Lucchino about tapping into Smith’s expertise. They worked out a deal that had her split her time between the two organizations.

When the demands of the Braves far outstripped those of the Orioles, Smith moved to a full-time role with Atlanta in 1994, but only under the condition that she keep Baltimore as her home. Each Tuesday, she was on the 5:40 a.m. flight to Atlanta, where she would plow through three busy days before returning to Baltimore to spend the next four with husband Bart Harvey and their three children, who were born in her first six years in Atlanta.

When Smith and Lucchino reunited with the Red Sox in 2002, she commuted to Boston from Baltimore. She does it now with the Dodgers, albeit with some adjustment because of the cross-country flights.

“It became apparent to me that it didn’t matter where she was on any given day, she was working her tail off,” said Kasten, who pointed out that Smith was working at the time she went into labor with two of her three children. “That is just who she is. So if this works better for her and it gives me access to her abilities by making it easier for her — I’m all in on that. It was the price we paid to get her talents and I was happy to pay it.”

Smith’s initial job in Atlanta was to tackle the design of an Olympic stadium that would be converted into a baseball stadium, a process executed only once before, in Montreal, with one of the cookie-cutter retractable-roof stadiums of the ’70s and ’80s.

The solution was a traditionally shaped ballpark, with four tiers, which bled into a two-tiered seating area in what later would be space beyond the outfield. Eliminating those tiers dropped capacity from 85,000 down to about 50,000 for baseball, but it also created a design problem: What to do with the vast open space created beyond center field, which led to even more open space dedicated to parking.

Thinking back to the success of Eutaw Street, Smith proposed a plaza, rimmed by ticket windows and a team store. Over time, it became overrun by inflatables, sponsor areas and stages, but when it opened Smith was pleased.

“In its early years it was a beautiful space,” she said. “I thought it got junked up a bit in the later years.

“You hate to be so proprietary about your work that you don’t like to see it evolve, because I think nothing is richer than the patina of time. If you had total control, it could become a really boring space. But there’s a fine balance between giving it another layer and mucking it up.”

Smith thought she’d be done with the Atlanta commute not long after Turner Field opened in 1997. But then Kasten “cooked up” the idea for Philips Arena. While Smith is not nearly as passionate about basketball or hockey as she is baseball, she was jazzed to put her urban planning skills to work on an arena that would connect to mass transit and the CNN Center.

With the arena open and not much sports development work left to be done, Smith moved her work life back to Baltimore in 2000, taking a job with Bill Struever, the developer who helped her convince the city to save the Camden Yards warehouse.

She’d been back at work in Baltimore for almost two years when she got a call from Lucchino, who was part of a John Henry-led group bidding for the Boston Red Sox. Lucchino said he was optimistic about them landing the team. He also said they hoped to keep Fenway Park rather than chase the new stadium that the previous owners sought.

“We’ve developed some plans and I just don’t know if we’re crazy or not,” Lucchino said. “Would you be willing to look at them?”

Smith agreed. A month later, she began a new commute to Boston.

It wasn’t clear at the start how much work there would be, or how long it would last. The Red Sox had not committed to saving Fenway, just improving it. While they had a wish list to work from, the projects would be presented for funding by the ownership group one at a time. Along the way, they would find out whether they threw off enough revenue to make the park viable in today’s MLB.

And so they came: Yawkey Way. Green Monster seats. The Big Concourse. Pockets of new seats — many of them premium — here and there and everywhere, often in overlooked or under-appreciated spots. Over the course of a decade they spent $285 million resurrecting a baseball landmark that had been given up for dead.

|

Smith’s home has remained in Baltimore throughout her years with the Braves, Red Sox and Dodgers. “It was the price we paid to get her talents and I was happy to pay it,” says Stan Kasten, who hired her for both Atlanta and Los Angeles.

Photo by: HARRY CONNOLLY

|

“That was a fun project for me because it felt like we were pulling Fenway from the brink of disaster,” Smith said. “That’s the way it felt, pretty much every day. It was like having a life preserver and standing on the edge of raging waters, and then being successful in pulling your victim out.”

The thing about working on stadium development for a team: Eventually, it runs dry of projects. Fortunately, as the last of the construction dust settled in Boston, Orioles owner Peter Angelos was talking about renovations for Camden Yards, closing in on two decades at the time.

Who better to finish Camden than the person who started it?

Leading a tour of today’s Camden Yards, Smith climbed a set of stairs from Eutaw Street to one of the few areas that was under utilized in the original ballpark design, the space beyond center field. Now, there is a roof deck, with a covered bar and space to mill around, similar to the Chop House concept that was popular at Turner Field and caught on elsewhere.

On one side, the deck overlooks the field. Another has a view of the skyline. Down below is the Orioles’ take on what the Yankees call Monument Park, only rather than plaques on a wall there are 7-foot-tall bronze statues of Frank Robinson, Jim Palmer, Brooks Robinson, Cal Ripken Jr., Eddie Murray and Earl Weaver, spread throughout a courtyard picnic area.

Those were two of the more obvious additions. Some were more subtle, but no less important to Smith.

When she worked with HOK on the original design, they did all they could to restore the warehouse. They cleaned the exterior without buffing out its imperfection, so the color of the brick changes subtly on the way up. They left the letters that marked the loading dock as they were, rather than scrubbing or repainting them. One thing they couldn’t fit into the budget or timeline was a true restoration of the building’s awning, which stretched the length of the structure.

This time, they redid it.

“I got to do when we came back for the 25th anniversary what we didn’t get to do originally,” Smith said. “One of them is this awning. It’s got this beautiful wood underneath it. This awning is an exact replica of the original awning on the building. When it went up in ’92, it was a facsimile. So when it had to be redone we got the original drawings and took the time to do it exactly right.

“I had some fun with my second set of things.”

■ ■ ■ ■

Behind the weathered brick of an old Baltimore row house, the offices of graphic designer David Ashton reveal the creative space of a man who is fond of history, art and the firm angles of the letter “A,” cut from varied woods and metals. Ashton had never worked on a sports project when he met Smith, who was working on her first.

They first encountered each other when she hired him to design a ticket sales brochure for the new Camden Yards. Smith was impressed and suggested he compete for the contract to produce the many “signature signs” that the Orioles planned for their new, historically inspired building, the “jewelry that wants to be on it,” as Smith called it.

Ashton won the job over several larger, more established firms, including the one that produced the graphic identity package for the 1984 Olympics. Smith chose the winner along with Maryland Stadium Authority head Bruce Hoffman. When she had all the proposals, she took them to his office and placed them on his desk, covers closed.

“Without opening one of these, pick the one you want to work with,” she said.

He chose Ashton’s. She agreed.

“It just looked like it belonged,” Smith said, examining the cover again 30 years later in Ashton’s offices. “I thought the other proposals addressed the project, but they were talking about themselves. Their firm’s identity. David just got it. He saw what we saw.”

|

Having worked with Smith in Atlanta, Stan Kasten (right) hired her to oversee planning and development for the Dodgers.

Photo by: AP IMAGES

|

It was Ashton whose hand was behind many of the elements that set Camden apart. It’s not just the architecture that was shape-shifting. It’s the watch-like face of the clock above the scoreboard. And the ornithologically correct, Oriole-shaped weather vanes that flank it. They’re the sort of touches that Smith has interspersed throughout each of the projects, a logo here, a photo there, signs that serve a purpose and add feel to the park at the same time. Working with a core of Baltimore-based artists and designers such as Ashton, Smith has made detail a priority, championing the sort of items that could just as easily have gotten lost.

“She is a very elegant woman,” Ashton said when asked to describe Smith, who sat a few arms’ lengths away. “Very sure of herself. And one of the hardest-working people I know on this earth.

“When do you sleep? Do you sleep? We get emails at 2 in the morning sometimes.”

Smith ducked her head, smiled sheepishly, then looked back up.

“Email is a bad thing for me because it gives away your bad work habits,” she said. “In the old days you could be up all night and people didn’t know what you did. Maybe you were just fast.”

At the offices of another Baltimore-based graphic design house, two creatives who have collaborated with Smith on all her ballpark projects since the mid ’90s chuckled and nodded when told that her secret was out.

“If I were 25 years old again I don’t think I could keep up with Janet and her energy level,” said Susan Perrin, an art consultant who worked with Smith on the Orioles, Red Sox and Dodgers projects and also has done work for the Chicago Cubs and San Diego Padres. “We all talk about it. It’s 10:30 and we’re going home in the van like zombies. And she rests for a minute and then says, ‘Let’s think about this again.’ And we’re on to trying something new. She’s extraordinary that way.”

Ronnie Younts met Smith not long after Camden opened, when he was working for Ashton’s firm. Their extraordinary results led him to roles on more than a dozen other stadiums and arenas, most of which were for other clients.

“When you’re on one of her projects, you’ve got someone steering the ship,” Younts said. “With other stadium projects I’m on, there doesn’t seem to be somebody who cares about what everybody is doing and is linking it all together. There isn’t a captain. There are people that care about this or this or this, but there’s not one person who cares about it all. You’re working with the concessions person over here and operations over there and the team over here. They all have their own ideas, and a lot of those may be great ideas, but there’s not anybody corralling those cats.

“I’ve worked on 20 different stadiums around the country. Her projects are like no other.”

In Campo Las Palmas, the Dodgers wanted to pay tribute to the success of their Dominican Winter League team by prominently featuring its many championship trophies. Some were on display in a trophy case, but termites had destroyed many of the bases.

Unwilling to abandon the idea, Smith found a carpenter who spent three days working to repair and restore them.

“One of the things we love about working with Janet is that she is forever cherishing those artifacts and the history,” Perrin said. “More than once somebody has said — Oh, those old things? Those trophies are useless. You’ll never get them restored. And Janet will say, ‘Oh no. We have to do that.’”

It has been that way going back to Smith’s first days in sports, when she took on Lucchino’s challenge to resurrect a style of ballpark that had survived in but a handful of cities. At the time, only a few books showed off the architectural details of the fabled stadiums that inspired Lucchino’s idea. So to acquire more, they hired a consultant, John Pastier, who had hundreds of photos, many of them taken from postcards.

Among the details that struck them were the decorative touches on the end seat of each aisle. The Polo Grounds had the interlocking “NY” of the Giants logo. Tigers Stadium had the olde English “D.”

Smith wanted seats that looked like those, which were wood, with slatted backs. She knew that, as a practical matter, they would have to go with molded plastic, but was pleasantly surprised to learn they could be made to look like they had slats. When she approached the manufacturer with the request to create a decorative end seat, she fully expected the custom work to be prohibitively expensive.

Turned out that since the mass-produced seats were open at the end, all they had to do was create a cast-iron insert. Rather than any of the four versions of Oriole that the club used in its logo from its hatching in 1954 to the opening of Camden, they went with a pair of script Bs, as used by the Orioles’ precursor, the Baltimore Baseball Club of the 1890s.

|

Smith oversaw the $100 million renovation of Dodger Stadium.

Photo by: JON SOOHOO

|

It was yet another example of Smith not only seeing a creative option where others had not, but also getting cooperation where she needed it, similarly to the way she did with Aramark when the Orioles wanted the concessionaire to move its service level out of the ground floor of the warehouse.

“There’s a big difference between just saying you want to do something and explaining why you want to do it,” Smith said. “At the start, it may not seem ideal to someone. But you’ll often find they’re not so dug in. It may be that they’ve just never been asked to think about it any differently.”

Lucchino said he and Smith worked so well together because they knew that, even though they might do battle while balancing artistic input with budgetary constraints, they shared many of the same values. Kasten, who is known as a prickly negotiator, joked that the elaborate plaza bars that were part of the Dodger Stadium renovations stemmed from his request for a drink cart with an umbrella.

“She has a great way about her,” Kasten said. “She’s very insistent and demanding on good design when she wants it. But she has a quality of dealing with people that makes it far smoother than if, say, I rode in with my bull-in-a-china-shop act.

“She is truly the iron fist and the velvet glove.”