Fox Sports President David Hill loved hockey the moment he saw it at the 1988 Calgary Olympics. “It’s fighting on ice,” he said recently. “I love it.”

The NHL, though, was not a big television draw, and Hill believed he knew why — in standard definition, it was impossible to see the puck on TV.

As Fox agreed to a heavily hyped five-year deal for NHL rights in 1994 that cost an average of about $31 million a year, he had an idea. “The only way to make this work would be to make the puck glow,” he said.

That led to FoxTrax, a technology that essentially put a “big blue fuzz ball over the puck, with a red rocket trail that had sparkles on it,” said the glowing puck’s inventor, Stan Honey.

The hype around the puck was breathless. Fox Sports billed it as “the greatest technological breakthrough in the history of sports” before its 1996 launch. It was a description that made Honey uneasy. “I mean, what about the wheel?” he asked.

The innovation immediately was panned by hockey fans, especially hard-core fans in Canada. A Toronto Sun columnist complained in 1996 that the glowing puck “pandered to the parts of the American audience that don’t know a hip check from a hippo.”

But the team of people who worked on the puck still love it and believe the increased TV ratings during that stretch prove that the technology drew casual fans. The glowing puck’s supporters continue to see it as a technology ahead of its time, and one that led to many sports TV innovations, like the virtual yellow first-down line on football telecasts.

“The term hadn’t been coined then, but the current term for what we did is augmented reality,” Honey said.

The people most closely involved with the glowing puck project — identified below with what their job titles were in 1996 — talked about the idea, development and presentation of a concept that lasted for just two NHL seasons but still stirs strong feelings today.

IN THE BEGINNING

■ DAVID HILL, President, Fox Sports: When we were building Fox Sports, hockey became available. But the sport’s ratings sucked. We didn’t pay a fortune for it. But when you buy a property, you figure that you can get the ratings up and make some money on it. I thought one way to do this would be to make the puck glow because nobody could see the puck on television. The idea of making the puck glow had been talked about forever, and people told me that it would never work.

|

Fox’s David Hill heard the criticism but said the experiment paid off with higher ratings.

Photo by: WILLIAM HAUSER / FOX SPORTS 1

|

■ STAN HONEY, Executive VP of Technology, News Corp.: I founded a company called Etak that pioneered vehicle navigation. Rupert Murdoch acquired it in 1989, and I became the chief executive of an operating division of News Corp. I found myself in a job I never wanted, which is a staff job of what was a $10 billion media company at the time. I was going crazy because all I was doing was flying around and going to meetings. So I was looking for projects where I could actually build stuff because that’s what I enjoy doing.

■ GARY BETTMAN, Commissioner, NHL: I’ll start with the caveat that this was more than 20 years ago. The best that I can remember is being with David Hill, and he told me about it. With Fox having just acquired the NHL’s rights, he was looking for a way to enhance what existing fans were seeing and find a way to introduce the fastest game on earth to people who might not have been hockey fans. I actually thought it had potential.

■ HONEY: Hilly [Hill’s nickname] had asked me to meet with him every week or so when I was in L.A. and brief him on technologies that could potentially impact the broadcast of sports. At one of those lunches in 1994, I described a technology that was just barely possible to create fake billboards during games, what is now called augmented reality. Those kinds of conversations with Hilly were invariably constructive. I would tell him something that was possible and he would tell me that it was the stupidest thing he’s ever heard. But then he’d say, “If that’s possible, could you do this other thing?” When I told him about the fake billboards, he asked if it would be possible to track and highlight the hockey puck. I told him that I thought it probably was.

■ JERRY GEPNER, Senior VP of Field Operations and Engineering, Fox Broadcasting: To an engineer, anything is possible. It’s just a matter of time and resources. David is a creative genius of the highest order. When a creative guy like David heard that the glowing puck had a non-zero possibility, in his mind it became a 100 percent certainty.

■ HILL: I really thought going into this, as genius as Stan is, that we would never make the puck glow. I figured that if it works or doesn’t, at least it would pop the ratings so that when we went on air, we had a story to tell the advertisers.

■ HONEY: After a week, I sent Hilly an email saying it would cost $2 million and would take two years. Probably 20 minutes after I sent Hilly that email, I got a call from Rupert, who said, “Hilly tells me that you can track and highlight the puck on live TV for $2 million in two years. Do it.”

■ GEPNER: Stan shows up in my office, and we sit down on the couch. Literally on pads of paper and napkins, we started drawing pictures of how this might work. It was a pure spitballing/brainstorming session. We didn’t come out of it with any clear idea, but we had confidence that two or three things might work. Within about 72 hours, we had a meeting set up in L.A. with Mr. Murdoch, David Hill, Chase Carey, Gary Bettman and Dave Defoe, who was the CFO for News Corp. The meeting was in a bungalow on the Fox lot to show them a demonstration of a glowing puck.

Stan and his engineers mocked up a puck that had a non-visible light (pulsating LEDs or something like that) in it. In order to see it, you had to put on these special glasses, sort of like the cardboard 3-D glasses you get at the movie theater. Lo and behold, it glowed, and everyone thought it was great. Stan and I knew that it bore no relationship whatsoever to what we might eventually build. Hasbro could have made it.

■ HILL: Early on, Stan calls me up and says, “I’ve got an idea. Plutonium.” He wanted to put plutonium in the pucks to make them glow! I said, you’re mad. The last thing I want to hear about is that there was a small nuclear explosion.

■ HONEY: There’s one story from David that isn’t true. David will tell you that I first suggested we do it by making the puck radioactive. Of course, that’s nonsense. That was never an approach that we considered. The guy who actually suggested that was Andy Setos, who was then the head of engineering at Fox. Andy’s a smart guy. I think Andy was joking.

■ HILL: It’s not a lie! He called me up late at night. It was plutonium. Just because he’s now regarded in yachting as a God [Honey is a member of the U.S. National Sailing Hall of Fame], these youthful indiscretions — like thinking of using plutonium to make the puck glow — he’s now trying to put this behind him. I can’t make this up. I’m not that smart.

■ GEPNER: I can perfectly believe that Stan said that in jest. At the same time, I can perfectly believe that David would have taken it seriously. That to me is a disconnect that I could believe would happen any day of the week. Stan has a very wry sense of humor.

THE TESTING

■ HONEY: We started a radio tracking system, where we put a radar transponder in the puck and we built radars around the side of the rink to measure distance to it. Then we did an optical system where the puck would emit infrared pulses and we would track it optically. We got them both to work. But the radar pucks were too expensive.

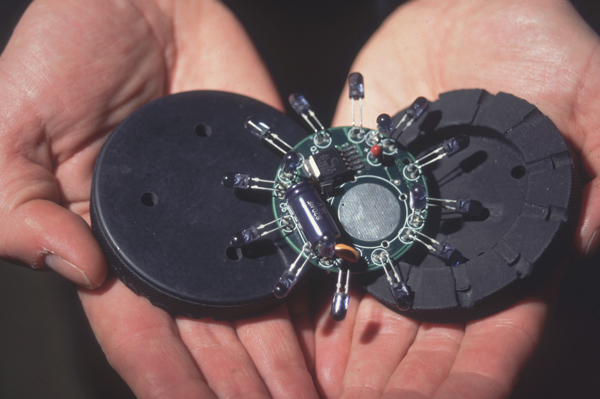

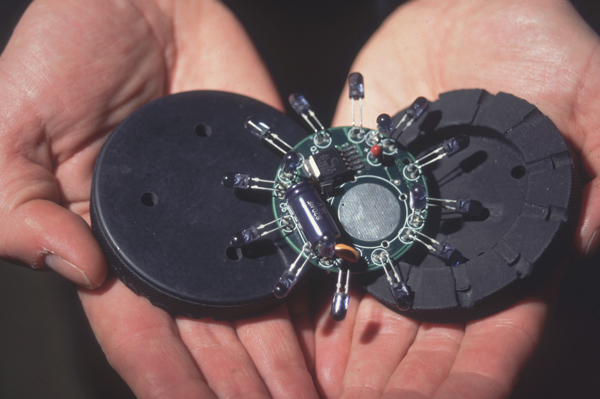

■ BRIAN BURKE, Senior VP of Hockey Operations, NHL: Gary came to me and asked if we could put these transmitters in a puck. I said, “Gary, I’m a hockey player and a lawyer. I don’t know anything about pucks or transmitters.” I flew to St. Jerome, Quebec, to visit the company that made our pucks, In Glas Co. They said they would have to take all the pucks, hacksaw them, and put the transmitters in and glue the tops back on. I’m like, “Glue the top back on?” I could imagine them splitting open on every slap shot. They said they would use an epoxy that’s like concrete. We used the prototypes in preseason games. These pucks cost $400 each.

■ GEPNER: The place that we did most of our testing was at what was called Brendan Byrne Arena, which is where the New Jersey Devils played. We tested it a bunch. A certain number of pucks every game get shot into the stands. We would go to the person who caught the puck and try to trade a new official puck for the glowing one because they were so expensive. In one test game, a rookie goalie won his first game. He was keeping the puck. We went and talked to him. He said, “This was my first win in the NHL. I don’t care if it’s worth more than a Fabergé egg to you. You can’t have it.”

|

Engineers came up with the idea of placing transmitters inside the pucks.

Photo by: GETTY IMAGES

|

■ BURKE: I remember one of the first tests was in Boston. One of these pucks went into the crowd, we had to race over to them with some volunteer and say, “Here, we’ll give you another puck, and we’ll give you a T-shirt.” The first two or three guys were like, “F--- you. I’m keeping this puck.” I think we lost $1,200 in that first game. But the pucks worked. And most importantly, they didn’t come apart when they were slapped or hit the boards or goalpost. An average puck back then might have cost $1 to $2. The glowing pucks dropped to $14 to $15 per puck eventually.

■ BILL SQUADRON, Senior VP of Strategic Planning, News Corp.: Because of the battery power requirement for the puck and because it was emitting infrared signals, it had to be hit by a stick every once in a while to activate it. What that meant was that if a puck went into the stands, we had to hope that someone wouldn’t bounce the puck on the floor because then suddenly you’d have two pucks being activated in the arena, and that would throw off all the sensors.

■ GEPNER: We had to put up something like 30 infrared cameras above each ice rink to track the puck. We bought a collection of several dozen — probably close to 100 — infrared cameras, made by a company called Polnik. We came up with a grid pattern where we had to deploy these cameras in the catwalk and the lighting grid of every arena. We had to install these things and take them out after every game. The arenas did not have cables running to these locations, so every installation required 15,000 to 25,000 feet of cable. You had to get power to each one of them.

If somebody told me today that I had to do that, I’d laugh at them. Part of this is that we were too young and ambitious to have any idea that we shouldn’t really be doing this. This is like somebody giving you a set of Lincoln Logs and saying go build a house I can live in.

■ ERIC SHANKS, Broadcast Associate, Fox Sports: Its big debut was the All-Star Game in 1996. We go into the Fleet Center [in Boston] and the thing just doesn’t work in the days before the game. It doesn’t work at all. This is a problem. It turns out that because it was infrared, the lights in Fleet Center work at a certain frequency that made the puck invisible. We started out trying to make the puck glow, and it actually made the puck invisible. Stan said there were a couple of options. We could switch out all the lights in Fleet Center. That’s not going to work. At the end of the day, they ended up coming up with a different infrared frequency or filter to make it work.

■ HONEY: Hilly came by our production truck at one point just before the introductory game and asked how it was going. I said, “No problem.” Meanwhile, the system was in one of its states where it wasn’t working. My engineers looked at me aghast as soon as Hilly left the truck and said, “Why did you tell him that?” I said, “I’m banking on the fact that we’ll figure out what the problem is. The last thing we need is for Hilly to be scared shitless like the rest of us.”

THE GAME

■ HILL: I funneled the money out of the marketing budget, which [Fox Sports marketing executive] Tracy Dolgin got pissed off about. It suddenly disappeared from his budget, and it went to Stan. If we can make the puck glow, it sells itself. There’s going to be haters, and everyone’s going to write about it. So we go to Boston to launch it at the All-Star Game. Suddenly, hockey’s hot. There’s journalists everywhere. I thought to myself, this has paid off. I don’t care if it doesn’t work because at least the audience that we’re going to get for the first game will stay with it because it’s so much fun. And it worked! Although, it didn’t work very well, to be honest. It had too much of a delay.

■ VINCE WLADIKA, Senior VP of Media Relations, Fox Sports: In one day, we actually had three separate stories in three different sections of USA Today. The Boston Globe — a broadsheet — devoted an entire page for a diagram showing how the puck actually worked. We definitely overdelivered in terms of the PR, which offset whatever marketing David said that was cut back.

■ LOU D’ERMILIO, VP of Media Relations, Fox Sports: There was a ton of publicity. It was on “World News Tonight” and Popular Mechanics. Letterman did a skit on it. I’ve never been contacted by Popular Mechanics before or since. It was so innovative and different. It was one of those situations where a lot of the press coverage came to us.

■ WLADIKA: Two days before the All-Star Game, we had an event at the Fleet Center. We brought in the Bruins minor league hockey team from Providence and had them do an on-ice demonstration. We had Doc Emrick host it. We had both TVs set up in front of the media, as well as the big video board over the ice. Somebody flipped a switch. The first thing I remember was hearing [New York Post columnist] Phil Mushnick go, “Wow!” At that point I said, alright. That’s good because there was Mr. Grumpy going, Wow! He actually wrote a column: “This puck’s for you.”

■ JERRY STEINBERG, Technical Manager, Fox Sports: Some writer asked Sandy Grossman, who was the director at the time, what are the traditional hockey fans in Canada going to say about the glowing puck? And Sandy said, “F--- them.”

■ BETTMAN: I remember Doc Emrick’s words. It was like launching a spaceship. “Now we’re going to engage the puck.” There was a moment in time where it was clear that they were throwing a switch and activating it. The All-Star Game did a big number for an All-Star Game in those days because people wanted to see what this was going to be like. And I think it was people beyond hockey fans. [The game drew a 4.1 rating on Fox, which at the time was the highest-rated NHL telecast in 16 years.]

■ DOC EMRICK, NHL Announcer, Fox Sports: The great announcer Dick Enberg once said some of the best ad libs are written down. I probably had the ad lib written down that day because it was so significant that you wanted to make sure you said it right. But what I said I don’t recall.

■ ED GOREN, Executive Producer, Fox Sports: There was an interesting moment — I don’t recall the principles — after one of our glowing puck games on Fox, in the postgame press conference, when one of the goalies was questioned about a goal that he let in, his comment was, “I would have stopped it, but I got distracted by the glowing part of the puck.” Of course, it had no effect on the live event. God knows what he was thinking. I don’t think anyone bought into his explanation as to how he let in a soft goal.

■ EMRICK: I thought the All-Star Game was a great place to reveal it for the first time. The All-Star Game needs something unique to add to it. In addition, the game had its own theatrics because, of all things, Raymond Bourque, one of the local guys, scored the winning goal late in the game. The contest itself was really good. But the added effects that the FoxTrax brought made it, probably, the most memorable All-Star Game that I’ve done.

THE REACTION

■ HILL: The Canadians went batshit. The Toronto Globe and Mail published a cartoon, which I wish I had kept, which said, “Memo to David Hill: how to watch hockey.” It showed a pair of glasses. The Canadians took it as a personal affront that anyone would try to do something with hockey.

■ BETTMAN: The reason our avid fans didn’t embrace it was because it was a little primitive. The glow didn’t always wind up on the puck. When the puck was against the boards, the glow was in the stands. It wasn’t as refined as Sportvision was able to make it at a recent All-Star Game or even the recent World Cup, where we just used the most advanced version of it.

■ HILL: Of course the hard-core fans hated it. You’d find that in any sport. When you change and popularize any sport, the hard-core fans have this little club, and they think they’re special because they’re the only ones that know. As soon as you open it up to other people, they hate that.

■ HONEY: I got death threats. I think they were in jest, but you never know. A lot of them came from old college friends. I went to Yale, and I knew a bunch of hockey players. When they found out I was responsible for it, I got a load of grief.

|

Fresh from signing a new rights deal with the NHL, Fox needed a way to attract casual fans.

Photo by: GETTY IMAGES

|

■ SHANKS: One of the only times that my courage for working at Fox was tested was when we did a playoff game in Canada, Rangers at Canadiens. I was the broadcast associate on the game. It was the first time the “puck truck” — the production truck used to power the glowing puck — had ever left the United States to go up to Montreal to do this game. That morning, as I’m pulling up, I see our TV trucks. Around the one truck, I see 100 really angry Canadians marching around the truck with picket signs that say “F--- the Puck” and “Down with the Puck.” One of the signs was a huge picket sign of Rupert’s head glowing that said, “Go Home.” I had to cross the glowing puck picket line to get to work that day. The funny thing is that our feed of the glowing puck never made it into Canada. But they still organized a picket against us.

■ HILL: What happened is that hockey had the highest ratings it’s ever had during that period. It clearly worked. Then Gary Bettman decided that ESPN was a better home for hockey. ESPN didn’t want to use the glowing puck, so it went back to minus or negative ratings.

■ BETTMAN: It was the marketplace. ESPN and ABC showed — not that Fox didn’t — but the level of interest being shown to us by ESPN and ABC jointly was extraordinary. [Editor’s note: The NHL signed a five-year, $600 million deal that started in 1999. Fox was paying an average of $31 million a year.]

■ HILL: If Gary Bettman had any sense, he would have subsidized ESPN because he saw the ratings.

■ HONEY: I asked Jed Drake why he didn’t take it on, and he said that Fox had branded it so strongly as FoxTrax that it was basically crazy for them to take it on. Instead of continuing the technology and going to a much less in-your-face graphic view — ESPN could have continued the technology and gone to a much more subtle gray. Instead, because it had been so strongly branded Fox, they just dropped it.

■ JED DRAKE, VP of Remote Production, ESPN: The short answer is that we didn’t think at the time that it was an enhancement that we wanted to pursue. It had been on the air with Fox for some time. We were aware of what we thought was viewer reaction to it. We just made that decision that this was not going to be part of our portfolio of technical enhancements. It didn’t do a great deal for me. It’s one of those aesthetic things. Of course, it all became moot when we got to HD.

■ GOREN: ESPN plays to a different audience — a hard-core audience. The whole point of the glowing puck was to expand the fan base.

EPILOGUE

■ BETTMAN: We have been experimenting with puck and player tracking systems that can gather a variety of data as to both pucks and players — who’s on the ice, how fast they’re skating, where they’re located relative to each other, how much distance they’ve covered. As it relates to the puck, it’s the same thing. We’re also experimenting with the possibility of a “goal/no goal” puck because sometimes the view of whether or not the puck actually cleared the line and is in the net is inconclusive. We have been experimenting with the possibility of having a puck where you know exactly where it is. Because of the speed of the game, and the enclosed environment and all the equipment, it’s always been a challenge for us to know exactly where the puck is at all times.

■ HONEY: It was a nearly perfect project. We did it on time. It was frighteningly difficult. And we were very close to budget. I think we spent $2.2 million on it. So it came out really well. During the course of the development of the puck, we spent a lot of time with Hilly and Eric Shanks, who was then working for Hilly. Over lunches and dinners, we would speculate about other things you could do in sports. In those discussions, we basically talked about everything that we’ve done since, including pitch tracking and NASCAR and the yellow first-down line.

■ GOREN: When we got NASCAR, one of the problems in covering an auto race — after a few laps on your camera shot, the lead car could be the third car back in your shot, as that driver is closing in on lapping the two cars in front of him. What was absolutely brilliant in my mind, is that we were able to adapt the glowing puck technology to create a graphic in NASCAR that followed the car that you’re talking about. That really was a significant change in coverage of NASCAR.

■ STEINBERG: Today, because of how everybody wants to attract the younger audience, it’s probably a good time to bring it back. Your next generation of viewer has come up playing video games. It’s right in their power alley. You have to make it visually interesting. You have to jump into the 21st century. The glowing puck was a 21st-century device that happened in the 20th century.