|

The massive Grand Park complex near Indianapolis spans 400 acres.

Photo by: GRAND PARK

|

The mayor of Westfield, Ind., sat, hands folded, at a table that overlooked a vast expanse of artificial turf — three full-size soccer fields, side by side, all under a single roof spanning 370,000 square feet.

Location: Westfield, Ind.

Opened: June 2014

Size: 400 acres

Funding: City of Westfield, Holladay Properties

Total park visits: 1.5 million last year

Cost: $50 million

31 soccer/multipurpose fields

26 outdoor baseball/softball diamonds

Seven concession stands

Cost: $27 million

370,000-square-foot indoor facility

Three full-size soccer fields

Locker rooms

Office space

Meeting space

Full-service restaurant

Cost: $9 million

88,000-square-foot gym

Privately owned and financed

Eight courts for basketball or volleyball

Lounge area with views of all courts

Strength and conditioning area

Concession stand

Grand Park Hotel

Source: Grand Park

Rising from the cornfields about 40 minutes north of downtown Indianapolis, the Grand Park Events Center would seem to spring from nowhere were it not for the vast sports campus that surrounds it: A 400-acre swath of manicured green that also includes 31 soccer fields, 26 baseball and softball diamonds and eight basketball courts in an 88,000-square-foot field house.

For perspective, consider that the 1 1/2 mile-long, half-mile-wide parcel could fit the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, the Indianapolis Colts’ domed stadium, the Indiana Pacers’ arena and the Class AAA Indianapolis Indians’ ballpark — and still have room left for the Indianapolis Zoo.

Only 10 days removed from the center’s opening event last month, a Donald Trump rally that drew 10,000 and used only one-third of the facility’s floor space, Andy Cook thought back seven years, to the skeptics who panned the then first-term Westfield mayor when he tried to trademark the phrase “Family Sports Capital of America” for the city, and then set about to committing $60 million to try to make it so.

“Mayor, you’re nuts — that’s what the naysayers said,” said Cook, a Republican who came within 62 ballots of being voted out by opponents of his plan the first time he stood for re-election. “What would a little city like this be doing building the largest sports park in the country?

“Fortunately we also had some very supportive people who saw the value in this.”

While the eventual financing plan was complex, the value proposition was a simple one: Build a youth sports complex large enough to attract travel teams from across the country, whose families would spend their money in the area’s hotels and restaurants, would raise Westfield’s profile and drive further development. That, in turn, would increase the property tax base for a municipality that since 2000 has grown from 9,900 to 37,000.

Westfield ended up spending about $50 million on the initial Grand Park soccer and field-sports campus that opened in 2014, then used a public-private partnership to develop the $27 million events center, which opened in July. Private investors developed the $9 million field house.

|

The Grand Park complex includes a 370,000-square-foot events center that can fit three full-sized soccer fields.

Photo by: GRAND PARK

|

Visitor data from the first two years shows the complex far outperforming forecasts. Last year, Grand Park attracted more than 1.5 million visitors — 807,625 for baseball and 706,245 for soccer and other field sports. Importantly, 79 percent of baseball visitors and 64 percent of field sports visitors came from outside the area, generating more than 61,000 room nights for the region.

An economic impact report commissioned by the city estimated $97 million in visitor spending last year, up from $44 million in the first year of the facility. Total economic impact from the first two years of sports campus operations was $220 million, not counting construction activity.

All that was before Grand Park opened the field house, which this summer hosted a Nike basketball event that attracted 35 of the nation’s top 50 rising high school seniors, along with more than 200 college coaches who came to see them; or the events center, which should do a brisk indoor soccer business during the cold-weather months.

And it doesn’t include upticks in both field sports and baseball this year.

| Things to Know |

| Hired in October to help expand Ripken Baseball’s tournament and player-development operations, John Bramlette brings experience as a practicing attorney as well as a background in youth camps and travel baseball. Here are some of Bramlette’s considerations as he reviews Ripken’s plays in an increasingly competitive field. |

| 1 |

| “The facility experience has to be really good. That starts with between the lines. What kind of surface am I playing on? Is it something I can get around the corner or is it something worth traveling for? What are the dugouts like? Do the fields have lights? Are there certain elements of a big-league-type experience that really makes it feel special and different for your typical 9-, 10-, 12-, 14- or 16-year-old, whether it’s walk-up music or hearing your name announced? What is there other than that we’ve got fields and some teams and we’re playing?” |

| 2 |

| “The little, subtle, management of customer relations. Are the fields turned over quickly? Are they taken care of? Do we know where we’re playing? Is that information on my phone or do I have to go hunting for it? And all the other elements of the experience for coaches and parents that make the difference, so they’re not showing up and playing games where it might be a little haphazard.” |

| 3 |

| “A big part of this has become destination-driven. So if we’re going to come there and play a game at 9 in the morning, what are we doing at noon? What do we do for the rest of the day? Families would take vacations and then they’d go to a baseball tournament, so why not take those two and roll it into one and make it more economical and efficient for families that in previous years felt like they wanted to do both but were hard-pressed. We try to give people a lot of fun and family experiences that they’re going to cherish along with a great baseball experience.” |

| — Compiled by Bill King |

Consider the frenzy of activity at the facility on the last weekend in June. Grand Park hosted a six-day US Youth Soccer regional that attracted 216 boys’ and girls’ teams, with about 4,000 players, coaches and family members booking more than 10,000 room nights. On the baseball side that same weekend, three tournaments attracted more than 190 teams and 2,000 players.

“Somebody else may build a better facility or a bigger facility than this one day,” said Don Rawson, president of Indiana Sports Properties, which books and manages field sports at Grand Park. “Probably will. Maybe we’ll have to build something else to keep up. But, to my knowledge, nothing like this facility exists anywhere else on this planet right now.

“Sitting here in central Indiana, that’s a pretty good place to be.”

■ ■ ■ ■

Anyone involved in travel sports will tell you that an assessment of the burgeoning business must begin in one place: the parking lot.

Grand Park boasts 10 of them.

Early on a Saturday morning in July, Grand Park’s Lot E, adjacent to fields F19 through F29, told a familiar story. There was an SUV from Kentucky, parked next to a minivan from Colorado, which was next to a sedan from Minnesota. A bit farther down the row were plates from Michigan, Ohio and Illinois.

On four nearby fields, teams prepared to start the second day of the boys under-15 US Lacrosse National Championship tournament. Parents sat along the sidelines on canvas folding chairs, sipping coffee. Some set up tailgate canopies for shade. One bore a Utah Utes logo, another the “W” of the Wisconsin Badgers.

A club from Cincinnati made the shortest trip, driving about two hours. Its opponent came from Michigan. A team from New Jersey played one from Wisconsin. One from Utah played one from New York. Two teams from Colorado faced each other. Together the teams traveled about 6,600 miles each way for the three-day event, with seven coming more than 500 miles and three traveling more than 1,000 miles.

The baseball side of the complex was occupied by Pastime Tournaments, an Indianapolis-based event owner that went from attracting 85 teams to 10 tournaments a decade ago to bringing in more than 2,600 teams to about 130 tournaments last year. For its national championship tournaments at Grand Park, Pastime brought in 145 teams in the 18-and-under division and 50 more in the 14-and-under bracket, attracting entrants from seven Midwestern states and Ontario.

|

Westfield, Ind., mayor Andy Cook (fourth from right) cuts the ribbon on Grand Park with deputy mayor Todd Burtron (fourth from left) and tourism executive Mark Newman (third from right).

Photo by: GRAND PARK

|

That a baseball event owner could remain unaffiliated, working without the sanctioning of major national players such as the U.S. Specialty Sports Association or Perfect Game, speaks volumes about the turn the travel sports world has taken in recent years.

While teams had to qualify for automatic admission to the baseball event, the reality is that it was “open,” meaning that any team willing to pay the $975 to $1,275 entry fee was likely to be accepted. Though the lacrosse event attracted top teams, clubs could apply for at-large berths.

Once the parlance of the nation’s athletic elite, the term “travel team” has crossed over to the masses.

The numbers regularly recited by the municipalities, developers and other companies drawn to the youth sports boom are striking: An estimated 53 million U.S. youths traveling to compete in tournaments, their families spending about $7 billion annually on gas or airfare, lodging and food, feeding an industry segment now estimated to be worth anywhere from $8 billion to $10 billion annually.

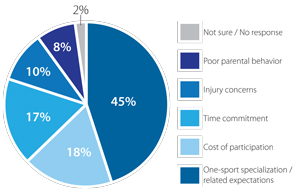

The following are results of the Turnkey Sports Poll taken in July. The survey covered more than 2,000 senior-level sports industry executives spanning professional and college sports.

Which of the following is the biggest challenge facing youth sports?

Which of the following sports would you encourage your child to play?

| Basketball |

81% |

| Golf |

80% |

| Soccer |

77% |

| Baseball |

71% |

| Tennis |

71% |

| Swimming |

71% |

| Hockey |

34% |

| Football |

29% |

| Wrestling |

19% |

| Not sure / No response |

1% |

As a player, coach or parent, have you ever been ejected from a game?

(Note: Respondents could select all that apply.)

Source: Turnkey Sports & Entertainment in conjunction with SportsBusiness Journal. Turnkey Intelligence specializes in research, measurement and lead generation for brands and properties. Visit www.turnkeyse.com.

Since opening in 2003, Clearwater, Fla.-based Sports Facilities Advisory has produced financing documents for more than $6 billion in youth and community-based sports projects. Its founder, Dev Pathik, said the firm receives 25 to 30 calls each week from communities it hasn’t heard from before, most of them asking about sports tourism.

“Anyone with a family-oriented destination is looking at this because of stats given to them by the U.S. Travel Association,” said Pathik, whose consulting firm also manages sports complexes of varying size. “Whether they’re on a beach or in the middle of nowhere, people are clamoring (for) this. It’s not right for every community. But they’re all asking.”

When Pathik discusses the growth of travel sports, he points to both the decline of funding for public school sports and increasing cost of college tuition as driving factors. Clubs and travel teams — particularly in soccer — began to grow in popularity in the 1990s, often pitched as the preferred path to a college scholarship. More kids playing for more clubs fueled more tournaments. Family travel destinations were among the first to catch on.

In 1997, Walt Disney World opened its ESPN Wide World of Sports complex. That was one year after the opening of Cooperstown Dreams Park, which hosts tournaments on 22 fields about five miles from the Hall of Fame. Myrtle Beach, S.C., and Gatlinburg, Tenn., were other early adopters.

During the most recent recession, as the convention and trade show businesses softened, youth sports tourism emerged as a darling; the only segment never to decline in a single quarter. In the last three years, it has grown 20 percent.

“I love the competition,” said Faron Kelley, vice president of the ESPN Wide World of Sports complex. “It is great for the industry. But what’s really key is that as these facilities get built, they have to say what will make them different from the one in the next county or the next state. Whether it’s a niche sport or the right alliance with a professional team or an apparel company, what is that piece that gives them a competitive advantage?”

As the market has grown, Disney has expanded its offering. The choices Disney made over the years have made it clear where it sees growth. Along with the baseball and softball diamonds, rectangular fields, track, tennis courts and field house that were part of the 244-acre complex when it opened, Disney added a second indoor facility that can accommodate six basketball courts or 12 volleyball courts in 2007 and has plans to open a third building that will host cheer and dance competitions at the end of next year.

|

The ESPN Disney Wide World of Sports complex has been thriving since it opened in 1997.

Photo by: ESPN DISNEY WIDE WORLD OF SPORTS

|

Demand has driven that expansion, helping private operators grow, tournament owners profit, and communities secure funding for facilities. But the travel sports boom is not without its share of critics.

The move to longer seasons and more games may be largely responsible for the increase in repetitive-use injuries among young athletes. Year-round tournament play has led to increased specialization and less of the multisport sampling recommended by child development experts and endorsed by most pro leagues and national governing bodies. Parents who pay for travel sports because they think it’s a higher level of play or instruction than its local recreational counterpart may find that’s not the case now that there are so many events.

“I think a lot of parents of kids with different degrees of talent are pumping money into a sport, falsely believing they’re going to get the exposure they need to get collegiate scholarships,” Pathik said. “They are swept up in a market driven by the rights holders, the tournament organizers. And what do you say when the title of the tournament is national championship? ‘OK, we’re going to nationals.’

“It is a bit of a Wild West. … But what shouldn’t get lost is the fact that it’s better that those 50 million visits that we’re getting occur than not. I think those kids are doing things that are better for them than the alternatives. And that can get lost here.”

|

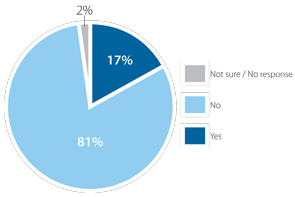

Ripken Baseball, led by hall of famer Cal Ripken Jr. (below) operates three complexes, including its original site in Aberdeen, Md., (bottom) and its newest site opening this year in Pigeon Forge, Tenn. All of its complexes model fields after major and minor league ballparks.

Photo by: RIPKEN BASEBALL (3)

|

Those who sanction and operate events point to their popularity as evidence that this is what families want. Many see the recent broadening of that market to include teams of all ability levels as a positive.

Ripken Baseball, owned by brothers Cal Ripken Jr. and Billy Ripken, now operates Ripken Experience baseball complexes in Myrtle Beach, S.C., and Pigeon Forge, Tenn., to go along with its original facility in Aberdeen, Md. With youth-scaled fields that replicate iconic major and minor league parks, the Ripkens believe they have a

model that can translate to other vacation destinations, driven by the desires of families.

“When we played in rec leagues or a Little League growing up, at the end of the year you put together your all-star team or tournament team and went around and played,” Cal Ripken Jr. recalled. “Now, when you do that, what’s left in the rec

leagues? You’re taking a lot of the talent away and people were scrambling around a little bit if they wanted to keep playing. I think they wanted to be able to have that same experience.

“Where there is a demand for that, we saw an opportunity to enhance the experience.”

While Ripken clearly favors locations with a tourist infrastructure for his facilities, which are programmed around weeklong tournaments and camps, others see opportunity in the weekend and four-day events that are the bread-and-butter of many travel teams.

Grand Park hosts some travel events that bleed into midweek, but the bulk of its events are built around shorter stays for families that want to get in and out on a weekend or over a holiday.

“We don’t have beaches and we don’t have mountains,” conceded William Knox, director of the Hamilton County Sports Authority, who served on the Westfield sports commission and has worked to land national events for the facility. “But our location will never change. We’re smack dab in the middle of the state and we have every interstate in the country coming into this location.

“All the bids we have submitted, all the event organizers have commented that we potentially could see an increased number of participants because of our location. And, when it comes down to it, they all want to draw more teams.”

■ ■ ■ ■

When Cook transitioned from president of Westfield’s town council to become the city’s first mayor in 2008, he faced a fiscal challenge that could have led to calamity.

A property tax cap adopted by the Indiana General Assembly was about to limit municipalities from collecting more than 1 percent of assessed value on residential property, 2 percent on apartments and farms, and 3 percent on commercial property.

For Westfield, a growing bedroom community populated largely by commuters, the implications were clear. If it continued to build neighborhoods, but not industry, its tax base would decline.

|

Myrtle Beach, S.C., home to the Myrtle Beach Sports Center, was an early adopter to youth sports travel destinations.

Photo by: MYRTLE BEACH SPORTS CENTER

|

Westfield needed to attract business.

The most obvious fit for a suburb springing from large parcels of farmland would have been office space. But Westfield’s neighbor to the south, Carmel, had locked up that market. Other popular options, such as warehouses or manufacturing, didn’t fit the city’s location or profile. High tech was a pipe dream for a Midwest city its size.

“Nothing out there was right for us,” Cook said. “So we began to look at what kind of an industry we could create.

“This is pretty boring, ugly country, OK. So what do you do with this flat, boring land? Well, it’s great for athletic fields. We’re also centrally located, within a day’s drive of two-thirds of the U.S. population. Those are the assets. What can we put together?”

As the town was trying to grow its tax base, it was dealing with the growing pains of a suburb its size: Its baseball, soccer and basketball programs were trying to cram more and more kids into aging facilities. Cook and others wondered whether they might find a singular solution for both problems. Working with the Hamilton County Convention and Visitors Bureau, they formed a sports commission to look into possibilities.

The first concept they came up with was for four to six baseball diamonds and six full-size soccer fields. Cook chided them for thinking “like Hoosiers,” humbly assuming that they should build only enough to meet their need, with a tad more to attract a half-dozen modest tournaments to help pay the bills. He wanted to not only play in the youth tournament market, but lead it, creating differentiation by offering enough fields to play a large tournament without teams trekking from complex to complex.

Rather than building to meet demand, they chose the opposite route, identifying a 400-acre parcel of affordable farmland in an accessible location and fitting all they could within it.

|

Rocky Top Sports World in Gatlinburg, Tenn., is an 80-acre campus in the heart of the Smoky Mountains.

Photo by: ROCKY TOP SPORTS WORLD

|

On a scouting trip to Elizabethtown Sports Park, a 158-acre complex about 45 minutes south of Louisville, Ky., Cook was impressed by the quality of the 24 fields, half for baseball and the other half for soccer and field sports. Told that the facility was operated by the city, he was surprised.

“How many people you have out here in the summer?” Cook asked.

“About 150,” he was told.

“I only have 300 employees in the whole city,” Cook said. “We’re not going to do that.”

Instead, the city opted to strike partnership agreements with leaders in the two sports they intended to host, the Indiana Bulls travel baseball club, widely regarded as one of the better programs in the Midwest, and the Indiana Soccer Association, the umbrella organization for club soccer in the state. The two nonprofits each took responsibility for the operation, maintenance and marketing of their sides of the facility, receiving all revenue and paying all expenses. The city collects an annual lease fee, which Cook said will be used for capital expenditures. The new events center is managed by restaurant and catering operator Jonathan Byrd’s, which not only will provide food service via a cafeteria, but also book the building.

In a development befitting the overall Grand Park vision, the events center is about six times the size of the building originally planned, a 60,000-square-foot practice facility. But when the city heard of the demand for full-size indoor soccer pitches during the cold-weather months, it saw the opportunity to take its event business from nine months to 12. For the hotel and restaurant chains that Westfield hopes to attract, that could make for an easier sell.

To make the increased cost work, the city turned to a public-private partnership in which it would lease the building back from the developer, in the process guaranteeing the debt service. Cook said projections for rental income comfortably exceed the debt payments, though he acknowledged that the taxpayers are on the hook if that doesn’t happen.

“We know it’s going to work, but it was a political challenge to get that done,” Cook said. “We believe that if we create a profitable environment, the private sector will invest around it. Some cities give out tax breaks or credits or land. We’re not doing that. We’re creating something, and we think the economic development will follow.

“The underlying industry here is hospitality. It’s not making money off baseball and soccer. We were going to be in the tourism business. Here in Indiana that’s like an oxymoron, OK? Corn. Beans. That’s generally what we do.”

■ ■ ■ ■

On his way to Westfield for a ribbon-cutting at the events center, the executive director of Indiana’s office of tourism development made a quick stop at a Dairy Queen about 1 1/2 miles from the park. On the glass door was a handwritten sign: “Take your cleats off before you come in.”

It has become the city’s version of “No shirt, no shoes, no service.”

“Quite honestly, you can pursue large-scale national and international sporting events, NCAA events and the like, but the true economic impact and impact to the destination itself from a quality-of-life standpoint is far greater in youth sports,” said Mark Newman, who grew up in Westfield and played in the town’s youth soccer program. “Because you’re accomplishing two important things. You’re driving spending to your community. But you’re also creating an amenity the residents can use. In this era of quality of life, and what it is to a vibrant and vital community, to have something like this has transformed Westfield from a town into a city.

“Other communities across the state of Indiana are taking a page from their playbook.”

The Sports & Fitness Industry Association reported this summer that regular sports participation for kids 6-12 fell to 26.6 percent in 2015, down from 30.2 percent in 2014. The following are highlights of specific sports tracked by the association, and the participation trends over the past eight years.

| Sport |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2008-15 |

| Basketball |

16.6 |

14.4 |

15.3 |

15.5 |

14.1 |

16 |

14.7 |

14.7 |

down |

| Baseball |

16.5 |

14.5 |

14.1 |

14.9 |

12.5 |

14.2 |

12.9 |

13.2 |

down |

| Outdoor soccer |

10.4 |

10.4 |

10.9 |

11.2 |

9.2 |

9.3 |

9.1 |

8.9 |

down |

| Tackle football |

3.7 |

4.0 |

3.8 |

3.2 |

3.6 |

3.5 |

3.3 |

3.3 |

down |

| Gymnastics |

2.3 |

2.9 |

2.8 |

4.1 |

3.5 |

2.9 |

3.0 |

2.7 |

up |

| Flag football |

4.5 |

3.3 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

2.8 |

2.8 |

2.4 |

2.6 |

down |

| Volleyball (court) |

2.9 |

2.2 |

2.6 |

1.8 |

2.4 |

2.7 |

2.8 |

2.5 |

down |

| Ice hockey |

0.5 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

up |

| Track and field |

1.0 |

0.8 |

1.2 |

1.5 |

1.7 |

1.1 |

1.2 |

1.0 |

— |

| Lacrosse |

0.4 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.9 |

0.7 |

0.8 |

0.9 |

0.7 |

up |

| Wrestling |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.0 |

0.8 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

down |

| Field hockey |

0.4 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

up |

Source: Sports & Fitness Industry Association

As the first state to create a not-for-profit sports commission, Indiana long has been known for using its geography and the breadth of its facilities to attract sports events to Indianapolis. Now, Westfield is one of several smaller cities and suburbs employing a similar strategy.

Along with the economic impact figures, Westfield has hard numbers that indicate that the project is on its way to achieving its goal of increasing the commercial tax base. Three hotel projects that will total $30 million in land and construction costs are in the works. Assessed valuations on building permits this year are up 43 percent from two years ago. The 400 acres of farmland the city bought for about $14 million is now worth nearly $80 million.

Thanks to increased revenue from the commercial base, the city was able to reduce school taxes this year by about 9 percent.

“We’re so close to it, we can’t have the external view,” said Westfield Deputy Mayor Todd Burtron. “But the mayor and I often, in our private conversations, will look at each other and say we still really don’t know what we’ve done here.

“It just took a lot of guts.”