|

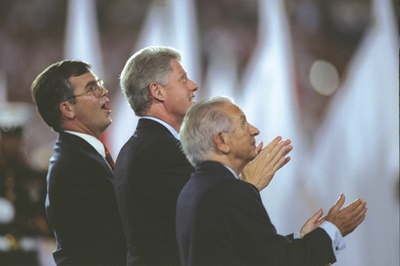

Tuesday marks 20 years since the opening ceremony of the centennial Olympic Games in Atlanta.

Photo by: GETTY IMAGES

|

Atlanta Olympics CEO Billy Payne was in shock.

It was 1992, and NationsBank CEO Hugh McColl Jr. had just agreed to a $40 million sponsorship of the Games, a deal several larger corporations had flatly refused.

At the last minute, Payne remembered his banking needs and chased McColl to the elevator.

“I forgot to ask you, we need $300 million [in financing] for the Olympic Stadium,” Payne recalls. “He says: ‘You got it.’”

With that surprising pledge, the pieces started coming together for the 1996 Atlanta Games, an event that began in Payne’s mind as an ambitious long shot and ended as a hallmark of U.S. sports history.

Tuesday marks 20 years since the opening ceremony in Atlanta, and in some ways that early meeting with McColl neatly summarizes the legacy of America’s last domestic Summer Games: unlikely, audacious, lucrative and, at least as far as Americans see it, successful.

Upon closer examination, Atlanta ’96 is a complicated matter. To the plus side, it gave the American South a global coming-out party, revitalized downtown Atlanta and still remains the most-attended Olympics in history. To the downside, it endured an act of deadly domestic terrorism, was criticized for being overly commercial, and struggled with transportation and technical problems that stick in the Olympic movement’s long memory.

Globally speaking, its most lasting effect is on how the Olympics does business. The International Olympic Committee made sure nobody ever quite put together a business plan for the Olympics the same way again. And after Atlanta put its own unique, quintessentially American spin on the Games, the IOC put much tighter conditions on local host committees and governments.

The DIY Games

In 1996, Payne and his team paid for the Games without much public help, covering the budget of $1.7 billion through sponsorships, TV broadcasting rights fees from NBC, merchandise, ticketing and licensing.

State and local government covered security and indirectly related infrastructure not included in the operating budget, but the Games budget included more than $500 million in construction costs for the Olympic Stadium, the aquatics center and athlete housing.

Without third-party private investors or government funding for those capital costs, the bid group was under extraordinary pressure to raise revenue.

The sales pressure intensified after the broadcasting rights generated less revenue than expected, in part because the Atlanta Committee for the Olympic Games was under pressure from lenders to lock down guaranteed revenue streams (at the time, local organizers and the IOC jointly negotiated rights).

The IOC didn’t like all the focus on fundraising, believing it distracted from the local organizers’ operational execution. The search for revenue led to the single most damning line hung on the Games, especially overseas: over-commercialized.

|

Billy Payne concedes the vendor stalls program was "unprofessional."

Photo by: GETTY IMAGES

|

Payne disagrees, conceding only to critiques of the city’s much-maligned, city-run program of vendor stalls in downtown Atlanta streets. He calls that program “unprofessional,” but says the Games’ private sponsorship and licensing was perfectly appropriate.

A.D. Frazier, then the committee’s chief operating officer, thinks the IOC looks foolish to criticize Atlanta, considering the government-backed profligacy of other Olympics. Their strategy required aggressive sales, but also forced fiscal discipline, he said.

“They’re so concerned about over-commercialization, and they’re the same people who brought you Sochi, a $50 billion event; London, a $12 billion event; and Rio. God only knows if they’ll get it done or not,” Frazier said in a recent interview. “Our little quote-unquote ‘over-commercialization’ doesn’t look so bad to me.”

After Atlanta, the IOC created a host city contract that requires the government to guarantee cost overruns. The document also requires the host city government to cede control to all outdoor advertising and commit to a centralized look and feel — also a reaction to a feeling that Atlanta’s freewheeling capitalism allowed ambush marketers like Nike and Samsung too much room to work.

Olympic Priorities

Many Atlantans consider the physical structures of the Games, paid for with the fruit of the Atlanta committee’s sales efforts rather than long-term debt, tax money or private developers, as perhaps their greatest legacy. Centennial Olympic Park, built for $75 million in private funds, created a new focal point in downtown out of nothing, spurring billions in additional private investment in the ensuing 20 years. Georgia State University and Georgia Tech got free dormitories, and Tech made a recreation center out of the aquatics venue. The Braves will soon leave Turner Field, and the Georgia Dome is heading for demolition, but as of this moment “eight or nine of the biggest [venues] are still in operation, still serving the community,” Payne notes with pride.

|

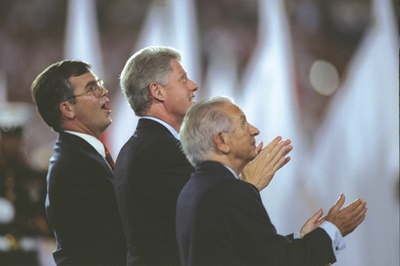

ACOG head Billy Payne, President Bill Clinton and IOC President Juan Antonio Samaranch have varied reactions during the Games’ opening.

Photo by: GETTY IMAGES

|

But to the IOC, it created a dynamic that prioritized revenue over getting the Games right. Michael Payne (no relation to Billy), then head of the IOC’s marketing operations, makes the case: “If the organizing committee hadn’t have had to build that stadium, they would have had the breathing room to properly test the technology, properly train the drivers, and to focus on the operational aspects that in the end were compromised.”

The IOC wanted to build a temporary stadium instead. Also, the IOC especially didn’t care for the ultimate beneficiary of the Olympic Stadium, Ted Turner. The Braves owner was noticeably absent among the official Olympics sponsor roster and had launched the Goodwill Games, a direct competitor, one decade earlier.

The Peoples’ Games

Whatever happened in the board rooms, the show in Atlanta was spectacular. Sprinter Michael Johnson’s dual world-record-breaking gold medals in the 200-meter and 400-meter races rank among the top accomplishments in sports history, and just last week, longtime NBC host Bob Costas called Muhammad Ali’s surprise lighting of the torch at the opening ceremony his No. 1 Olympic moment.

The operational problems were real, though. Tech provider IBM struggled to provide competition results accurately and promptly to journalists, the MARTA train line was overburdened, and bus drivers didn’t seem to know the city.

One night, Atlantan Ed Hula, founder of the Olympic trade publication Around the Rings, had to tell a driver to make a U-turn. “We’re going from the stadium to the Main Press Center, and he’s driving toward Macon. I got him turned around, but little episodes like that kept happening all the time.”

But the crowded, hot conditions in Atlanta didn’t seem to dampen enthusiasm. The record 8.3 million attendees were in good spirits, Hula remembers.

|

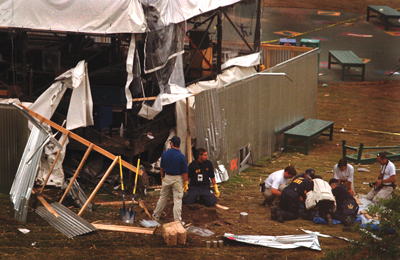

The bombing of Centennial Olympic Park claimed two lives and injured more than 100 people.

Photo by: GETTY IMAGES

|

“The people who came had a glorious time,” Frazier said. “The IOC expected a lot more in the way of luxury buses and motor coaches, but the fact of the matter is: The people who bought tickets — the people who the Olympics were made for in the first place — thought it was a great, great event, and I frankly don’t give a damn what the IOC thinks about it at this point.”

The dark spot came on July 27, when a pipe bomb laid by Eric Rudolph killed Georgian Alice Hawthorne, injured more than 100 others and contributed to Turkish cameraman Melih Uzunyol’s fatal heart attack. “My greatest regret is the bombing. My God, how could it not be?” said Billy Payne, who could see the crime scene from his office overlooking the park.

A long, agonizing night ended with the decision to keep the Games moving along. The next morning, 3,000 Games volunteers were expected to report for morning duty. Instead, all 10,000 for the entire day showed up, eager to know how they could help. “They showed their determination to not throw in the towel,” Payne said. “That was powerful.”

Taking stock

Now better known in contemporary sports circles as the chairman of Augusta National, Billy Payne is still the Olympics chief to most Atlantans. He answers the legacy question by focusing on the work first and the result second.

“It was proof positive that when we all push together in the same direction, we can accomplish a really impossible goal,” he said. “You don’t need any greater case study or evidence than a small group of friends, then a larger group of volunteers, then the community itself, coalescing and unifying to capture this wonderful opportunity.”

|

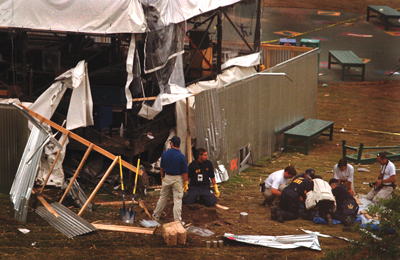

The Games revitalized Atlanta and were hugely watched and attended, but some remember them for commercialism, traffic and terrorism.

Photo by: GETTY IMAGES

|

In an era when skepticism about the Olympics is rampant, Atlanta is a city that’s proud of its Games and holds the movement in high regard. For most of the past 20 years, people would stop Payne every day to share a memory, he says, a pattern that’s only slowed as generations change.

“The legacy of pride and participation are as strong today as it was the day the Games were over,” he said, “and you know, the memories are diminished only as the people go away over the years.”

Even Michael Payne, the former IOC staffer, admits that the international perspective doesn’t carry much weight in the U.S. “It gave the legacy of a great park, provided a baseball stadium and helped reinforce Atlanta’s credentials as a major convention city and all of that,” he said.

In hindsight, the Atlanta Games look like it all worked out, even though the work along the way was tense, risky, frantic at times and challenging. Not unlike Billy Payne’s meeting with McColl after so many other sponsors had said no.

“This was a long shot, but we were neither crazy nor stupid,” Payne said. “We had a lot of very smart people who were on our team from the very beginning, so do not confuse improbable with accidental.”