|

As part of History 600-016: Baseball & Society Since WWII, Bud Selig spends much of the class time discussing his life in baseball.

Photo by: ANDY MANIS PHOTO

|

Bud Selig pivoted in the passenger seat of the black SUV, reaching back for a sandwich wrapped in aluminum foil.

“I got grilled cheese and I think the rest of you got the best corned beef in America,” baseball’s commissioner emeritus said, surveying the lunch order from Jake’s, the old-school Milwaukee deli that he has owned since 1969.

It was a rainy Tuesday afternoon in April, and Selig was headed west on I-94 from his downtown office to the University of Wisconsin-Madison, an 80-minute trip he has made most weeks since September, when he embarked upon a second act teaching an undergraduate seminar in the history department at his alma mater.

Selig long has said that had he not found his way into baseball, he’d have been a history professor, a path he veered from only because his father persuaded him to spend a year in the family’s car-leasing business rather than heading to graduate school after he finished military service in 1958.

Living in Milwaukee for the first time since the city landed a major league franchise, Selig became enamored with his hometown Braves, going to as many games as he could and buying about $25,000 worth of stock when the team made a small percentage of shares available to the public in an effort to quell concerns about out-of-town ownership.

His addiction to that team, and the understanding of the blow dealt to his city when it left in 1966, would lead to a dogged quest to bring baseball back to Milwaukee, which would result in his purchase and relocation of a team, followed by his unprecedented ascension from owner to commissioner.

What lives and breathes between those three touchstones — rabid fan, small-market owner and reform-minded commissioner — is the personal history that Selig brings each Tuesday to Madison, where he joins 16 undergraduate students and associate department chair David McDonald for History 600-016: Baseball & Society Since WWII.

The capstone seminar covers not only Selig’s experiences, but the vast changes in the game and their reflection of the broader society at the time. They begin with Jackie Robinson, then explore the move west of the Dodgers and Giants, and work their way forward, studying expansion, relocation, labor relations, globalization, the impact of new ballparks and the fallout from steroids, among other topics.

Each week, students are assigned two or three outside readings on a topic and encouraged to find anything they can on their own. Selig, who typically spends weekdays in Milwaukee and weekends at his winter home in Phoenix, reads the assigned magazine stories or book chapters while on the plane.

He meets McDonald in an office that the history department has provided, which is decorated with a mix of artwork and knickknacks from both baseball and the Badgers. Together, they head to class, where students sit along the walls, with Selig, any guests he might bring and McDonald at the front.

McDonald opens by asking about the readings, making his way around the room, framing a discussion that leads into remarks on the topic from Selig, who then invites questions.

On the day that they discussed new ballparks, students raised arguments against public funding, questioned the viability of both markets in Florida, asked about the stratospheric prices for the best seats at Yankee Stadium and suggested that municipalities that fund new facilities might be entitled to a larger cut of their revenue.

For nearly two hours, he discussed each of their points candidly, sharing stories about the Brewers’ arduous fight for public funding for Miller Park and observations about other owners’ experiences.

“You know, when I was a kid in Madison, where we’re going today, I really did want to be a history professor,” Selig said on the ride from Milwaukee. “That was really my dream. I mean that. Now, it took me until I was past age 80. But I knew I would enjoy it. I’ve lived through so much and gone through so much over the last 50 years, the thought of sharing that really appealed to me.”

As the black SUV neared its Madison exit, Selig reached into his bag for a syllabus to share, scanning it to be sure it was the right one. A day earlier, he was on campus at Arizona State, speaking to students in the new sports law and business program, where he has accepted a post as a distinguished professor. The next day, he would be in class at Marquette’s law school, where he has been a sports law adjunct for six years and lectured eight times this semester.

While he is quick to point out that the Marquette experience has been rewarding and he has high hopes for his new relationship with Arizona State, the fact that the Wisconsin gig is at his alma mater, in the subject that he studied, has made for an especially engaging and rewarding experience.

“I love history,” Selig said. “But this is different.

“This is history I’ve lived.”

■ ■ ■ ■

The students were riveted.

The topic for the day was “The Political Economy of Stadium Construction,” to be highlighted by Selig’s own experience wrangling funding for the $400 million retractable-roof stadium that would be known as Miller Park.

As Selig wrapped up a review of what he often has called baseball’s renaissance period, with 22 clubs erecting new ballparks in as many years, a student asked a question about the political process that Selig encountered.

Often, the student pointed out, a city’s mayor would stand boot to boot alongside team owners as they lobbied for taxpayer financing. He wanted to know whether that was the case for Selig in Milwaukee.

“No, it wasn’t,” Selig said, shaking his head somberly. “In fact, my book someday will for the first time …

He paused for a moment, as if deciding whether to continue.

“When I was a kid in Madison, where we’re going today, I really did want to be a history professor. That was really my dream. I mean that. Now, it took me until I was past age 80. But I knew I would enjoy it. I’ve lived through so much and gone through so much over the last 50 years, the thought of sharing that really appealed to me.”

BUD SELIG

“The mayor was a disaster,” Selig said.

“Who was mayor?” McDonald asked.

“Norquist,” Selig said. “John Norquist. Don’t get me started.”

But the starting gate was open and Selig was off.

“It was a strange story,” he said. “Take this view.”

Then he shared some of the untold aspects of the Brewers’ stadium story, as could only someone who had lived it.

“I’m trying to keep a team in Milwaukee,” Selig said. “I wouldn’t move a team. Somebody else is going to have to move it. So we’re trying to find a solution.

“I bring [then-Commissioner] Bart Giamatti here. And [the mayor] talks me into the site that we’re now on. Which is a great site, by the way. Every freeway in the Midwest connects right there. Parks 15,000 cars. Our fans love to tailgate.”

Only, as Selig tells it, the mayor wasn’t committed to that site, at least not once the debate heated up.

As opposition to the taxes needed to fund the stadium mounted, Norquist began pointing toward a location downtown. But, Selig said, he never proposed a site that could have worked.

Selig told the story of a call from the mayor’s staff to his daughter, Wendy, who then ran the team. They wanted to discuss a potential site. Quoting his father, who often said “talk to everybody,” Selig suggested she take the meeting.

The site they showed her was north of the Bradley Center, where the Bucks play. From even a cursory look, there were obvious flaws. There was an incline that would have created engineering problems. Access was poor. There was little parking.

To top it off, there was a church registered as a historic site.

“You can’t move it,” Selig told the class. “I don’t know. I guess he thought they’d pray in the outfield.”

The next morning, Selig got a call from an old fraternity brother, a real estate developer who wanted the ballpark downtown but was disappointed by the suggested site.

|

Of the politics involved in building Miller Park in the 1990s, Selig says, “This is the kind of stuff, to this day, you can’t figure out.”

Photo by: ANDY MANIS PHOTO

|

“What’s the joke?” the developer began, launching into a rundown of flaws with the site.

“He called it sophomoric,” Selig said. “Then he hung up.”

Selig told another story of a time he was in Phoenix and, upon calling his office from a pay phone to check for messages, he learned he’d gotten an urgent call from an alderwoman. He headed home to return the call.

When he reached her, she was with all the other members of the city council. Having read that the mayor had floated a $50 million proposal to the Brewers without the council’s approval, they were calling to inform Selig that the club had “no chance to get 50 cents, never mind $50 million.”

“This is the kind of stuff that, to this day, you can’t figure out,” Selig said.

Now, to be clear, just as Selig points out that these were the events from his view, there were others who took the opposite view during what devolved into a combative, emotionally charged, sometimes “vicious” — Selig’s word — political throwdown.

When Selig signed on to teach the course, McDonald wondered how the former commissioner would react to the need to teach a balanced version of subject matter that was rife with disputes, considering that Selig played a central role in many of them. He found that while Selig remains outspoken in his views, he acknowledges dissent and, in most cases, respects the dissenters.

“He reads every [assigned] article, including some that are highly critical of him,” McDonald said. “And even when he doesn’t agree, he will always recognize what he thinks is fair criticism and what he thinks is misinformed. He’s very good about distinguishing between those with students.”

Considering the labor strife that marked Selig’s first three decades in the game, the unit on the MLB Players Association and former Executive Director Marvin Miller was guaranteed to generate robust discussion.

“That’s when I came to understand [Selig’s] essential fairness,” McDonald said. “For as much as he’s an advocate for certain points of view, he recognized that the relationship was professionally adversarial. Miller was doing his job. He was effective and did his job very well. Conflict was going to be part of it.”

In developing the curriculum for the week devoted to stadium development, McDonald chose as one of the assigned readings a paper by University of Chicago economist Allen Sanderson, who, like many in the field, has argued against public funding for stadiums and arenas. Selig joked that he’d have thrown Sanderson’s paper out the window were he not cruising at more than 35,000 feet while reading it on his way back from Phoenix the previous day.

The two have a history of clashing in this debate, going back to a program Selig appeared on at the Commercial Club of Chicago, where Sanderson kept “raising his hand and raising all sorts of issues.”

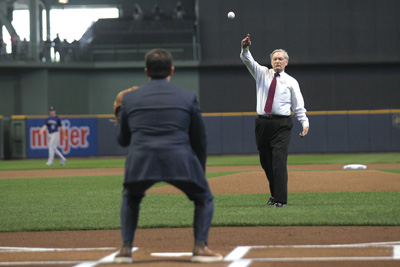

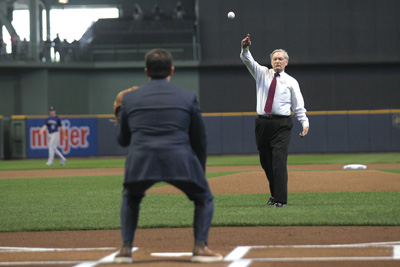

|

Newly retired after 22 years as MLB commissioner, Selig throws out the first pitch on Opening Day at Miller Park in 2015.

Photo by: GETTY IMAGES

|

While arguing the value of stadiums in class, Selig trotted out a favorite line from senator and Vice President Hubert Humphrey, who during the debate over whether to build a stadium for the Twins and Vikings in the ’70s famously said that they could allow both franchises to leave town, but then they’d just be “a cold Des Moines, Iowa.”

“I wasn’t too hard on Sanderson, was I?” Selig asked after arriving back at his campus office after class. “I know economists will disagree, as we’re all entitled to disagree, and I’ve said that [in class].

“But, boy — Sanderson.”

His voice trailed off and he shook his head. Hearing chatter coming from the reception area outside his office, where the MLB staffers who made the trip with him had gathered around a laptop on a desk, Selig poked his head out to see what he was missing.

The Brewers had a day game, and they were watching the stream on a laptop.

“What’s the score?” Selig asked.

■ ■ ■ ■

Standing at the front of a lecture hall filled with a mix of Madison locals and Wisconsin students — including granddaughter Marissa Savitch, who is a hurdler at the school — Selig concluded the opening portion of the latest installment in his “Conversations with the Commissioner” lecture series with an invitation.

“I can talk all day about any of these subjects, but I want to encourage you to ask a lot of questions,” Selig said. “I’ve got my granddaughter here in the front row. Oh … you look like you might be falling asleep.”

The crowd chuckled.

“So let’s be blunt,” Selig said. “I’ll tell you the story I always tell people to encourage candor.”

About five years ago, Selig asked for questions at the end of a speaking engagement in Milwaukee. A woman raised her hand but quickly put it down. Selig asked what was the matter.

“Ohhh,” she said with a thick Wisconsin accent, “this is a nasty question.”

“Let me tell you something,” Selig said. “When I took over in 1992, I was a quiet, thoughtful, sensitive guy with a lot of feelings. I don’t have any feelings left so you can’t hurt ’em. … So go ahead, on any subject you want.”

They took him up on it.

For the next 45 minutes, the audience offered questions about ticket prices, the finances of the New York Mets, the wild cards, Shoeless Joe Jackson, sabermetrics, steroids, public financing of stadiums, baseball in Cuba, using the All-Star Game to determine home-field advantage in the World Series, instant replay, returning baseball to Montreal and about a half-dozen others, including, of course, Pete Rose.

“No, that’s all right. That’s a perfectly good question,” Selig said when some in the crowd moaned at Rose’s mention. “When I have speaking engagements I always make a bet with myself about how long will it take to get to Pete Rose.”

When you combined Selig’s prepared remarks with the unscripted exchange that followed them, the 90-minute session tied together most all of the major themes, reforms and events of Selig’s 22 years as either commissioner or acting commissioner.

There was hope and faith, the phrase most associated with his tenure as commissioner. When the chasm between a handful of high-revenue clubs and the rest reached an unprecedented level in the 1990s, Selig began speaking forcefully about the need for hope and faith in every market.

It took time, but the message resonated.

|

Selig laughs with then Texas Rangers owner and future President George W. Bush (left) and former MLB Commissioner Fay Vincent in 1992.

Photo by: AP IMAGES

|

As he often does when speaking about the topic, Selig told the story of an infamous meeting in Kohler, Wis., where owners all but brawled over the polarizing issue of revenue sharing. So bad was that meeting, Selig said, that when he asked former Texas Rangers owner George W. Bush how he was doing while on a visit to the White House at a trying time in 2004, Bush said, “If I can survive Kohler, I can survive anything.”

There was a story about the creation of MLB Advanced Media, the internet company that distributes profits equally among all clubs.

Known for his insistence on 30-0 votes, Selig was one vote short of unanimous as he headed to the owners meeting at which MLB would decide whether to pool its clubs’ digital rights. As often was the case, the last holdout was Yankees owner George Steinbrenner.

The night before the vote, Selig and his wife, Sue, had dinner with Steinbrenner.

“That’s socialism,” Steinbrenner said when Selig brought the plan up at dinner. “You’re not going to do that.”

“Ah, Georgie, you can go along,” Sue Selig said several times.

“Naaaah, I’m not,” Steinbrenner said. “I’m tired of these guys.”

“George, I can’t do it without you,” Selig said. “It has to get 30 votes.”

“You got all the rest of those dopes?” Steinbrenner asked.

“Yeah, I got ’em,” Selig said.

The dinner conversation returned to more pleasant matters, but at the end of the night it was clear Steinbrenner hadn’t budged.

“I’m not in, I’m not in, I’m not in,” he muttered on the way out. “I’m not doing it.”

|

Of building consensus among owners, Selig tells students, “If they voted 30-0, they couldn’t bitch and whine for the next two years.”

Photo by: ANDY MANIS PHOTO

|

“If you want to kill this deal,” Selig said, “you kill the deal.”

It seemed an odd choice of words, considering they both knew Selig had an overwhelming majority. But this was one of many times that he would refuse to move forward until he knew he had every last vote.

“Why did I want 30-0 votes?” Selig asked the room in Madison. “Because if they voted 30-0, they couldn’t bitch and whine for the next two years about what they had done.”

As the vote proceeded the next day, each club had responded affirmatively when it got to the New York Yankees.

“New York Yankees,” the secretary called.

Silence.

“New York Yankees.”

“Now you hear this: Grrrah. Grrraah,” Selig said, trying to replicate the guttural noises he heard coming from somewhere in the meeting room. “Finally, after what seemed like an eternity, this voice says: ‘Yeah. I don’t know why but, yeah.’ And there was a lot of applause and that was it.

“And the story of BAM is really a great success story.”

■ ■ ■ ■

Ask Selig for a rundown of his day, any day, and he is almost certain to start with a mention of his workout streak, which as of that Tuesday in April stood at 2,839 days. He is a creature of habit, as sure as Sandy Koufax was a lefty. Lunch at one of a few places. Haircut at 10 a.m. on a Friday. Adding emeritus to his title has not changed that.

Among his standing dates is lunch with Chicago White Sox owner Jerry Reinsdorf, whom he meets at a deli most weekend afternoons when the two are at their Phoenix homes in the winter.

“He seems to be adjusting very well to whatever this new phase of his life is. He enjoys the teaching jobs. He’s going about it the right way. He’s stepped aside. As far as I can tell, he’s not bothering Rob [Manfred, his successor]. I’m sure Rob is making decisions he doesn’t like, but that’s always the way it is when you step away. He has to not let that bother him. And I don’t think it is.”

JERRY REINSDORF,

CHICAGO WHITE SOX OWNER

AND LONGTIME SELIG FRIEND

There could be no better barometer than Reinsdorf for the way Selig has taken to his new role.

“He’s doing great, far as I can tell,” said Reinsdorf, who has spoken with Selig most days for the last 25 years. “He seems to be adjusting very well to whatever this new phase of his life is. He enjoys the teaching jobs.

“He’s going about it the right way. He’s stepped aside. As far as I can tell, he’s not bothering Rob [Manfred, his successor]. I’m sure Rob is making decisions he doesn’t like, but that’s always the way it is when you step away. He has to not let that bother him. And I don’t think it is.”

Reinsdorf jokes that rather than fretting about attendance, as he did when he owned the Brewers, or a coming vote, as when he was commissioner, Selig has taken to tracking the receipts at Jake’s Deli.

“He seems to be fixated on that,” Reinsdorf said, chuckling.

Selig, 81, points out that he had plenty of time to contemplate what this role would be like, since he had a runway of almost two years to prepare for it. There were a few emotional moments, like when he received a lengthy standing ovation at his final owners meeting and when he accepted an award from the New York chapter of the baseball writers association on his final night as commissioner.

|

Selig, with Hank Aaron in 2014, says of writing a book, “stories are what I’ve done for the last five decades.”

Photo by: SCOTT PAULUS / MILWAUKEE BUSINESS JOURNAL

|

He was touched by things many said about him during what became a farewell tour. But he swears that when he went to bed that night in his Manhattan hotel room, there was no memorable exchange with his wife or particular sense of finality. “This had been going on so long that we were prepared for it,” Selig said. “I don’t know how else to say it, other than that it was just time.

“The pressures of the job were day to day, hour to hour, minute to minute. There’s less of that now. So it’s different. I still talk to a lot of people and I’m still busy. Just maybe not as hectic and pressured.

“I don’t miss much, I have to tell you. Probably because what I’m doing now has been even more interesting and more rewarding than I would have thought.”

Along with teaching, Selig is at work on a memoir that he promises will provide an unvarnished recount of his life in baseball. The idea was born in 2009, at the Hall of Fame induction of Rickey Henderson, Jim Rice and Joe Gordon, where historian Doris Kearns Goodwin was listening as he and Hank Aaron swapped shared memories.

“Commissioner, you’ve got to write a book,” she told him. “You’ve got to tell these stories.”

“I had never thought of it that way,” Selig said as he headed east back to Milwaukee, “because stories are what I’ve done for the last five decades.”