Editor’s note: This story is revised from the print edition.

When Oregon visited Stanford four years ago in a showdown of top-10 teams, the most expensive ticket was $40.

This season, when the Ducks return to Palo Alto, a ticket will cost as much as $120 through Stanford’s dynamic pricing model. On the other hand, a few games on the Cardinal’s schedule will offer tickets at a $20 introductory price.

The evolution of ticket pricing at Stanford, for the most part, mirrors the trends across the country, where variable pricing is now commonplace and a handful of schools are using dynamic pricing to adjust the prices on an almost daily basis, based on market conditions.

|

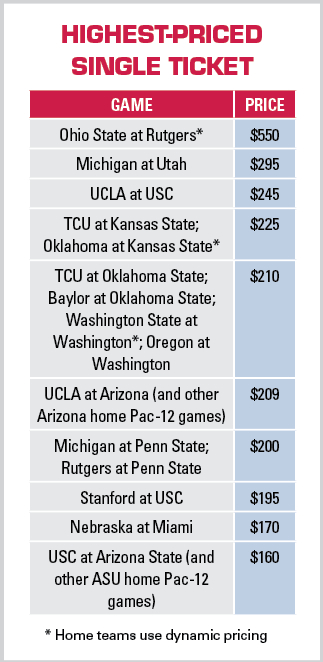

When defending national champion Ohio State rolls into Rutgers University this season, fans wanting some of the best seats along midfield will need to pay $550 per ticket.

Photo by: Getty Images |

“Gone are the days where every ticket is priced the same,” said Rob Sine, president of IMG Learfield Ticket Solutions, a sales and marketing business that works with more than 30 colleges. “Schools are understanding that every opponent and every sight line is not the same, and they’re pricing their tickets accordingly.”

Sine and other ticketing experts in college football say pricing strategies have changed greatly in the last two to three years. Schools not long ago employed fixed pricing on their single-game tickets. Now, practically every game has its own price point.

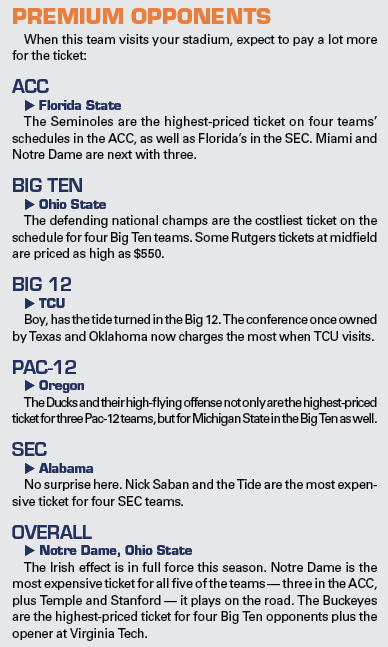

The most expensive single-game ticket in the country belongs to Rutgers, which is selling a limited number of midfield seats — fewer than 100 — to the Ohio State game for $550, according to a SportsBusiness Journal survey of ticket prices in the power five conferences.

That’s not a premium seat with amenities and there’s no required donation or seat license built into the price. It’s simply what Rutgers believes the ticket is worth to see the home team battle the defending national champs, based on the school’s research of the secondary market with the help of partner Tix City.

Ticket price survey

See a school-by-school breakdown of ticket prices among the 65 schools in the power five conferences.

Click here to see the highlights of our exclusive research.

Also, think you know ticket buying behavior among college students? Think again. Check out highlights from one recent study of Texas students.

The survey also found that single-game tickets to at least 15 different college football games this season are selling for $200 and up. That’s up dramatically from last season, when there were only five, and three of those belonged to Rutgers as part of its dynamic pricing strategy.

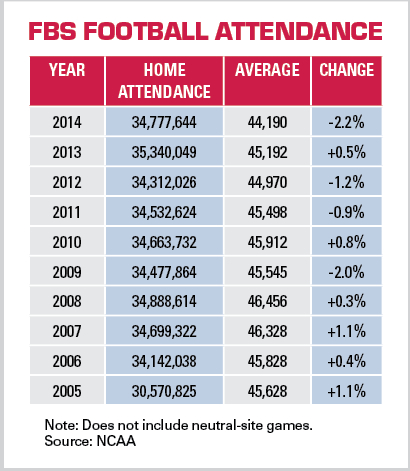

That brings up another point: While attendance is on the decline, ticket prices for the best games are going up.

The average attendance among FBS schools last season was 44,190, the lowest since at least 2003, according to NCAA records.

But the counterintuitive trends in ticket pricing reflect how schools are trying to capture every drop of revenue, especially when they see their tickets on the secondary market selling well above face value.

“What you’re seeing is that schools have access to more information from the secondary market and they’re using that to price their tickets,” said Kim Damron, senior vice president of client partnerships and marketing at Spectra Ticketing, the software company formerly known as Paciolan.

A dynamic strategy?

While the allure of additional revenue makes dynamic pricing attractive to some schools, others remain skeptical that their fans will embrace the concept.

At least three schools — Michigan, Northwestern and Tennessee — that were using some form of dynamic pricing in the past decided not to use it this season.

For schools that are attempting to dynamically price on their own, it’s time-consuming and manpower-intensive to constantly manage and monitor the flow of secondary ticket data, along with other factors in pricing.

Some schools have used a third party like dynamic pricing specialists Digonex or Qcue to price tickets. Others use Tix City, StubHub or Vivid Seats, among others, to provide detailed information from the secondary market, which becomes a gauge for pricing.

Sometimes, schools have found, it’s just easier to price the tickets before the season and be done with it. That’s why, even for schools that use dynamic pricing, it’s usually in effect for just two or three games a season.

The future of dynamic pricing in the college space “is an interesting question,” said Scott Garrett, Kansas State’s associate AD for ticketing and fan strategies. “As technology makes it easier to manage, I do think you’ll see more adopt it, and more third parties helping to manage it. But it can be cumbersome for your ticket personnel. The easier it gets, the more schools will be more aggressive with it.”

In a 2014 CBSSports.com story about dynamic pricing, Tennessee’s assistant AD for ticketing, Joe

Arnone, predicted that every school in the country would be using some form of dynamic pricing in five years because of the secondary market data available.

But a year later, Tennessee is no longer using dynamic pricing, even though the Vols have high-profile home games against Georgia, Oklahoma and South Carolina that conceivably could fetch much higher prices than the $90 to $105 face value.

“I just don’t think our administration was comfortable with ticket prices that could have been $250 or more,” Arnone said.

Season tickets that also require a donation or a seat license are similar to dynamic pricing anyway, Arnone said. At Tennessee, every season ticket requires an additional donation, a practice that is common at most schools in the power five conferences. The better the seat, the higher the required donation.

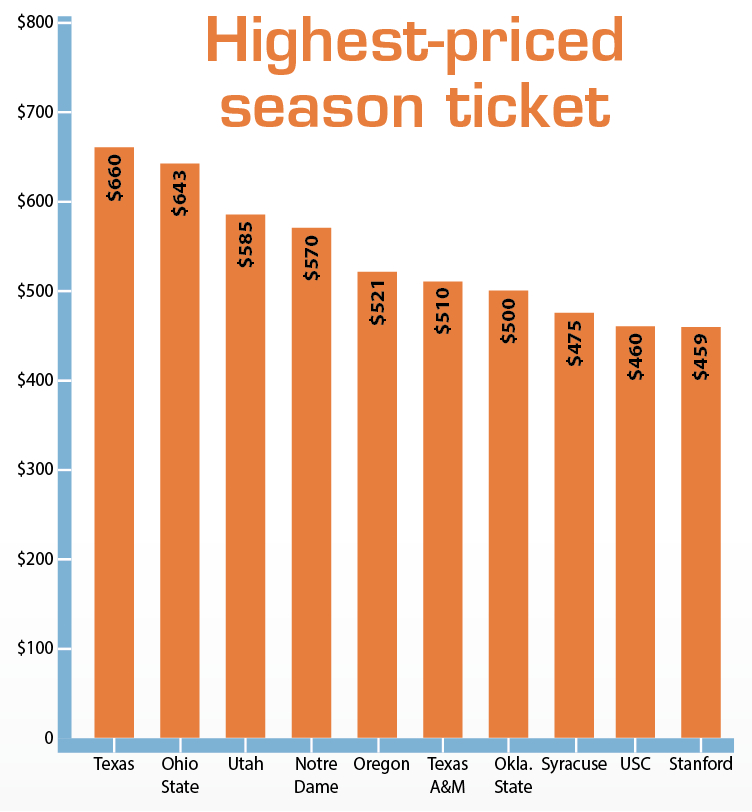

The best seat at Utah, for example, sells for $585, making it one of the most expensive season tickets in the country.

But the Utes also require a $500 donation, bringing the total price to $1,085 for a lower-level, midfield season ticket.

Even Northwestern, whose “Purple Pricing” strategy was considered groundbreaking three years ago, has tabled its version of dynamic pricing for this football season.

Under Purple Pricing, which was developed by a pair of Northwestern economists, ticket prices started high and only dropped. Those fans who paid higher prices early on received a refund for the difference based on how much the ticket prices fell.

Northwestern’s Mike Polisky, the deputy AD for external affairs, said the school was not getting rid of Purple Pricing, which will be back for basketball season. The school just didn’t think there were enough marquee games on the home schedule to warrant it.

Revenue driver

The schools using dynamic pricing typically limit it to single-game tickets for just a few games. As the demand goes up and the supply of tickets goes down, the prices begin to climb.

|

Schools are quick to cash in on marquee games such as a visit by Notre Dame.

Photo by: Getty Images |

In addition to the team’s strength and quality of opponent, schools evaluate the time of year, data from the secondary market, how well the opponent’s fans travel and attendance trends.

Dynamic pricing is most commonly used in pro sports, specifically Major League Baseball, where teams have 81 home games to sell. It’s far less prevalent in college football, where schools have six or seven home games per season. But schools such as Stanford and Rutgers have found it useful to maximize revenue from their best home games.

Rutgers reported that dynamic pricing was responsible for an additional $400,000 in ticketing revenue last season for a home schedule that included Penn State and Michigan. It’s also no coincidence that most schools using dynamic pricing — Arizona State, California, Rutgers, Stanford and Washington — are based in pro sports markets where fans are accustomed to the practice. But there are exceptions, such as Purdue and Mississippi State.

At the pro level, clubs can hunt for additional revenue by raising prices on a handful of the best seats, or lowering prices on lesser-quality seats as a way to sell remaining inventory in greater volume. In college sports, though, there’s not one method that’s universally used.

“With MLB, they might be making price changes per week or per day,” Damron said. “Colleges leveraging dynamic make changes far less frequently.”

Some schools start at a higher price point to capture that initial buying enthusiasm and work their way down as the game approaches.

Others start at a lower price point to reward those fans who buy early and then the price goes up as the game nears.

In each case, the schools say, the intent of dynamic pricing is to drive additional revenue, while also highlighting the value of the season ticket.

“We will raise and lower prices, but we do have a floor to protect our season-ticket holders,” said Geoff Brown, Rutgers’ chief marketing officer and senior associate AD, whose school works with Tix City to monitor market conditions and prices on the secondary market to help price the Scarlet Knights’ tickets.

Tiered pricing

Stanford has created its own method that it calls predictable dynamic pricing.

For its two premium home games this season against Oregon and Notre Dame, Stanford started selling single-game

tickets on Aug. 3 for $120. A week later, the price dropped to $110. By this week, the price will be $100 and next week $90. If any tickets are left by Aug. 31, Stanford will set prices based on the market.

Kevin Blue, Stanford’s senior associate athletic director for external relations, said customers who pay the higher prices early on are rewarded with the first selection of seats. Those fans who prefer to pay less can wait for the price to drop, but risk that the game will sell out.

Traditional dynamic pricing, which is employed at most schools that use a dynamic pricing strategy, fails to take advantage of the most enthusiastic buyers, Blue said.

“That’s the flaw in traditional dynamic pricing,” Blue said. “The most enthusiastic buyers, the ones most interested in attending the games, are willing to pay more. When you wait to raise the price, you’ve lost that revenue opportunity.”

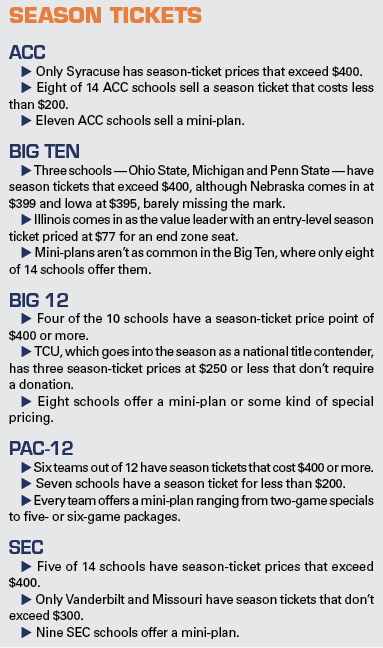

While the handful of schools that use dynamic pricing take unique approaches, every one of the schools in the power five leagues employ some form of variable pricing, depending on the opponent, whether it’s a conference game and how the ticket has sold in the past.

Stanford, for example, has significant differences in prices from its median ticket to the highest-priced ticket for a game against a marquee foe. The same thing is happening at Penn State. A ticket to a nonconference game starts at $40, but when Rutgers and Michigan come to Happy Valley, those tickets soar to $200 each.

Notre Dame’s home tickets range from $75 to $85 each for games against Georgia Tech, Massachusetts, Navy and Wake Forest, but the price elevates to $125 for games against Texas and Southern Cal.

But not every school uses variable pricing in such wide ranges. Wisconsin’s tickets start at $50 and go up to just $85 for the Iowa game, which is the Badgers’ most expensive single-game ticket.

The rub comes in the scheduling. Tougher opponents that create marquee games can lead to higher revenue, but also possibly a loss on the record.

“Schools are banking on their fans wanting to see the marquee matchups, and a lot of times in those higher-priced games, the fans of the visiting team travel,” said Ashwin Puri, associate AD for business revenue at California, a school that uses dynamic pricing for its single-game tickets. “It really brings to light the importance of scheduling and unique matchups. You only have a limited number of chances each season to maximize revenue so you have to take advantage of it.”