|

Participation in hockey has risen 44 percent among 6- to 17-year-olds in the five years since USA Hockey overhauled its youth programs.

Photo by: USA HOCKEY

|

When it instituted a trailblazing program that would become a model for athletic development across sports, USA Hockey anticipated a tough go, realizing it was slogging against the cultural current fueled by the emerging youth sports business.

Interstate travel. Year-round play. Single-sport specialization. “Elite” competition, too often defined by time and money invested rather than the actual level of play.

The architects of what would become USA Hockey’s American Development Model considered those trends to be more detrimental than developmental, particularly as they trickled down to the youngest children strapping on skates.

|

Travel teams and year-round training can limit a child to one sport, which some groups say leads to burnout.

Photo by: Getty Images |

And so, spurred by an internal study that revealed that 43 percent of children who tried hockey quit by age 9, the national governing body hit the reset button on its affiliated youth programs in 2010.

It pulled the plug on its 12-and-under pee wee national championship, reducing travel for younger players. It banned body-checking, responding to concerns about concussions. Most importantly, it laid out a boilerplate of recommendations — the skeleton of the ADM — adapting the game to make it more accessible and, in what was then an extreme example of zigging while its sports counterparts zagged, encouraging hockey players to play other sports.

Five years later, hockey not only has stemmed its decline, but reversed it, increasing participation 44 percent, from 517,000 to 743,000 among ages 6-17, according to recently released data from the Sports and Fitness Industry Association. That growth has come even as football, baseball, basketball and soccer all have watched youth participation fall during that same span (see chart).

So admired has been USA Hockey’s approach, the U.S. Olympic Committee adopted its principals for broader use, recommending that its 48 national governing bodies do the same.

“We’re like a lot of the other [national governing bodies], in that we can see what’s going on from the 30,000-foot level, but it’s hard to get to ice level and have an influence,” said Ken Martel, technical director of USA Hockey’s ADM program, who led both its design and implementation. “The average parent looks around and they go, ‘What we’re doing doesn’t seem right.’ In their gut, they know it’s not right. Why should my 9-year-old in Chicago have to travel to Boston to play in this tournament? All they hear is the loud voice of the youth coach who wants his piece of the glory or the business operation that’s going to take their money because they can convince you that your kid is the next coming.

“What we’re finding in our sport, because we’re preaching this, is that a lot of parents are going, ‘Whew. Thank you. I knew this wasn’t right.’ It’s nice to have someone who is actually saying so.”

As youth sports have taken off as a business, with weekend calendars chock-full of events that fill nearby hotel rooms and coaches of elite travel programs selling the promise of an athletic scholarship, the governing bodies that oversee those sports increasingly voice concern about the byproduct.

The tug for a child to choose one sport over another is a powerful one. The most successful club soccer programs and travel baseball and basketball teams offer year-round training and jam-packed tournament schedules. Some require parents to sign commitment forms that promise not only that the child won’t play for another team in that sport, but that they will prioritize that team’s activities over those in any other sport.

Sport specialization and year-round play long have been linked to burnout in sports such as tennis and figure skating. But doctors now also recognize a physical toll, suggesting that overtraining is behind an increase in injuries.

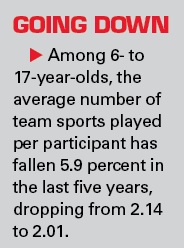

Even as some kids are playing one sport too much, more kids than ever are playing no sport at all. Inactivity among children 6-17 approached 20 percent last year, continuing a disturbing trend spanning the last six years. While much of the evidence is anecdotal, several national governing body heads said they worry that the push to specialize early weeds out good athletes before they have a chance to emerge. Among 6- to 17-year-olds, the average number of team sports played per participant has fallen 5.9 percent in the last five years, dropping from 2.14 to 2.01, according to the SFIA.

“We have millions of kids playing soccer,” Martel said. “But they’ll lose to Tobago. The last Olympics, we got pounded in the bronze game [in hockey] by Finland. We’ve got more kids playing hockey in the state of Michigan than they do in all of Finland.

“We have all these resources. We have 100,000 8-year-olds playing hockey. But we burn them up and turn them around. Not only is it not what’s best for the kids, it’s not what’s best for the sport.”

With those trends as a backdrop, youth participation became a key item on the agenda at the most recent meeting of the Association of Chief Executives for Sport, which brought together the heads of the nonprofit NGBs in Detroit in June.

Galvanized by a presentation by Skip Gilbert, the U.S. Tennis Association’s managing director of professional tennis operations, they agreed to work together more closely to address common problems.

“We’re each in our own little silos, worried about what we’re doing about these similar problems,” Martel said. “We seem to be replicating the same effort. We’re fighting the culture in our society. You talk to each other, and you realize it’s not just about any one sport.”

“We’re starting to come together around this, and that’s a step in the right direction,” said Jim Tooley, CEO and executive director of USA Basketball. “It’s hard to legislate an unlegislatable space. It’s really free rein out there.

What we’re trying to do is educate people — coaches and parents and everyone involved — to get kids going in the right direction at a younger age.

“Until you can solve greed, it’s a tough problem to put to bed. But getting the right information out there is the start.”

Next month at the U.S. Open, the USTA will join other pro leagues at a press event meant to tell the story of elite athletes who played multiple sports as children. Perhaps more significantly, the U.S. Open also will serve as the venue for two days of meetings organized by the Aspen Institute’s Project Play, bringing together representatives from about a dozen NGBs and most of the major pro leagues to discuss ways they can work together to address concerns about youth sports.

Participants by ages 6-17

| |

2009 (000s) |

2014 (000s) |

Pct. Change |

| Baseball |

7,012 |

6,711 |

-4.3% |

| Basketball |

10,404 |

9,694 |

-6.8% |

| Field hockey |

438 |

370 |

-15.5% |

| Football (tackle) |

3,962 |

3,254 |

-17.9% |

| Football (touch) |

3,005 |

2,032 |

-32.4% |

| Gymnastics |

2,510 |

2,809 |

11.9% |

| Ice hockey |

517 |

743 |

43.7% |

| Lacrosse |

624 |

804 |

28.8% |

| Rugby |

150 |

301 |

100.7% |

| Soccer (indoor) |

2,456 |

2,172 |

-11.6% |

| Soccer (outdoor) |

8,360 |

7,656 |

-8.4% |

| Softball (fast-pitch) |

988 |

1,004 |

1.6% |

| Softball (slow-pitch) |

1,827 |

1,622 |

-11.2% |

| Track and field |

2,697 |

2,417 |

-10.4% |

| Volleyball (court) |

3,420 |

2,680 |

-21.6% |

| Volleyball (sand/beach) |

532 |

652 |

22.6% |

| Wrestling |

1,385 |

805 |

-41.9% |

Source: 2015 SFIA U.S. Trends in Team Sports Report

“It’d be terrific if, collectively, the [National Federation of State High School Associations], the NCAA and the professional leagues were all saying the same thing,” said Scott Hallenbeck, executive director of USA Football.

“When that happens, that becomes a powerful message. Parents have gotten consumed by the almighty scholarship and the notion that if my kid is showing some promise I’ve got to get him in this pipeline. I don’t know that there’s evidence that works. And there may be evidence that they’re better off if they don’t do that. So we need to tell them that.

“Parents want to do well by their kids and help them. What they need is information and guidance.”

Not all the NGBs are in step on the issue of sport specialization. Even the experts who warn against the detriments of it concede that it may be necessary in some sports, such as gymnastics and swimming. Many of the world’s premier soccer players came up through youth systems that identified them before they turned 10 and plugged them into club development pipelines.

While that may be the direction that U.S. Soccer takes as it develops its national team, the sport’s youth umbrella is in step with its counterparts in spreading the word about the benefits of playing more than one sport.

“We have so much evidence out there that says that the multisport athlete is both more likely to succeed and less likely to get hurt, and that’s the message that we need to send to families who are trying to navigate all this,” said Chris Moore, who joined U.S. Youth Soccer as its CEO in January. “Don’t get me wrong. I want kids playing soccer. But it shouldn’t be all or nothing.”

Business pressures

There are financial considerations here, even for organizations that operate as nonprofits, and especially for the facilities that serve them.

Martel is not naïve about the business realities of youth hockey. Ice time is expensive. So part of his approach toward youth programs and facility operators is to make a business case for adopting the ADM recommendations.

He anticipated resistance when they recommended that all players in the younger divisions play cross-ice — shrinking the playing surface by putting pads and other barriers down to create a child-sized rink.

That would be an incredible waste of an expensive plot of frozen real estate. So USA Hockey suggested that rink owners take that same practice slot that they once rented to a team of 15 players to four or five teams that could play at the same time.

Not only did that increase facilities’ revenue — freeing up slots to bring in more programs — it also brought down the cost to families in a sport that traditionally has been seen as the most expensive of any to play.

“We’re making the sport more accessible,” Martel said. “And at the same time, from the business angle, you’ve got 50 people in the facility instead of 15. Even if they’re splitting the same cost, you’ve got more people at the concessions stands and more in the pro shop.

“We do have some authority and some control over those organizations under our umbrella. There are levers you can pull to get them to move in certain directions. Especially if you can show them how to make their money.”

Often, it is a matter of getting messages from the top of the organization, which traditionally has dealt mostly with U.S. teams and national championship tournaments, down to parents trying to make the decisions that are best for their children.

The pressing issue facing youth football is the increased awareness of long-term damage caused by concussions, which has figured heavily in the largest youth participation decline of any of the major team sports.

To address that concern, USA Football instituted a program called Heads Up Football, which requires that coaches

|

Soccer often requires big commitments because of jammed-packed tournament schedules.

Photo by: Getty Images |

be certified in proper blocking and tackling techniques (see related story, Page 16). Each program must send one coach to a daylong training session sanctioned by USA Football. That coach then instructs other coaches in the techniques.

About 6,500 of the 9,500 USA Football affiliated leagues have implemented the Heads Up program, Hallenbeck said. But the reality is, there is little that USA Football can do to make an organization comply.

“We don’t run youth football leagues,” Hallenbeck said. “We reach out and say Mr. or Mrs. Commissioner, it’s important that you embrace a better, safer game so you can look parents in the eye and tell them you’re addressing their concerns.

“If all of a sudden you hear from the top coaches that this is the best way to do things, parents pay attention and leagues pay attention. What we say to the NFL is, ‘You’re an amazing promotional and communications platform.

We’ll be the grassroots organization that implements. But we need you to be that voice box that says Heads Up Football is important.’ I can scream it all day long. As soon as they say it, it resonates.”

Over the last decade, Little League Baseball has worked more closely with Major League Baseball, never evidenced more clearly than last summer, when newly elected Commissioner Rob Manfred went to Williamsport, Pa., for the Little League World Series.

Through both that relationship and the pulpit that its jewel event gets on ESPN, Little League has worked to communicate directly with parents who may receive a conflicting message from their child’s travel team coach or the former junior college player offering lessons at the nearby batting cages.

“I would hesitate to be critical of a parent trying to do their best for their child, which is where a lot of this comes from,” said Little League International CEO Steve Keener. “It’s well-intended and their hearts are in the right place.

The big job is to explain to them that it doesn’t have to be so intense at such a young age.

“We just need to not give up. We have to keep at it, and bring as much information as we can to parents to make them understand that playing year-round and specializing may work for a handful of kids, but for the vast majority it has negative outcomes.”