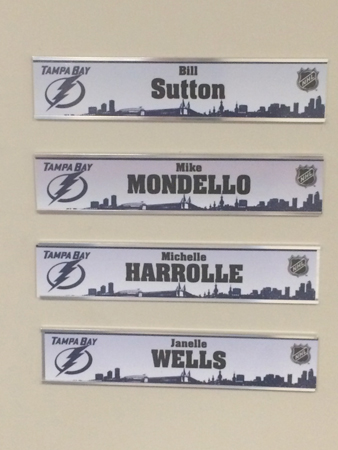

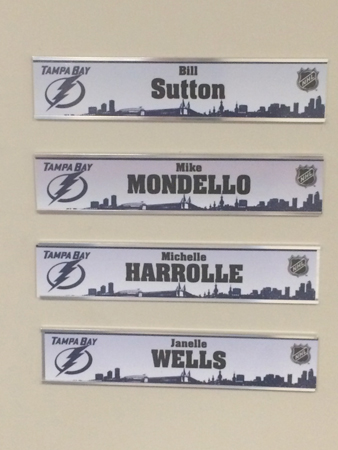

When you enter the Tampa Bay Lightning executive offices, the first door to the left is framed on one side by four nameplates, none of which belong to an employee of the franchise.

Not technically, at least.

“It’s not just four names on a door,” said Steve Griggs, the Lightning president. “They’re part of the culture. There’s an office for them to work from. There’s access.”

This is the room set aside for University of South Florida sports management faculty. The names on the plates are theirs.

Three days each week, you likely will see at least one of them here. You also will see 10 second-year sports MBA students serving residencies, working 20 hours a week in various departments across the franchise, much of it spent on projects designed to round out the practical side of their education while filling a franchise need.

|

Tampa Bay Lightning owner Jeff Vinik (left) presents USF’s Bill Sutton with a jersey as the team’s partnership with the school is announced.

Photo by: University of South Florida |

The other 17 second-years in the program will spend the coming academic year in similar residencies at sports and entertainment properties across the Tampa Bay region: Five in USF athletics, three at the Tampa Bay Rays, three at the Seminole Hard Rock Hotel and Casino and one each at IMG College, Fox Sports Florida, VF Majestic, the Tampa Bay Sports Commission, the WTA and Florida Hospital.

The residency comes with a tuition waiver, meaning students get their second year of school for free while making about $12 an hour, or $8,000 to $10,000 for the year. This year, the program will place all entering first-year students in part-time jobs with those properties or similar ones, further reducing the expense associated with the dual degree program, which confers a master’s in sports administration and an MBA.

Tuition and fees for the program would be about $26,000 for in-state students and $50,000 for out-of-staters without the waiver. With it, the cost is reduced to about $16,000 and $31,000, respectively.

When longtime professor and former NBA executive Bill Sutton came to USF in 2012, he saw the opportunity to create a program unlike any in the country. Not only did he have the unprecedented support of the Lightning but also a plethora of other sports properties to tap into, both for residencies and projects. He had the support of the university and its business school, which wanted to make sports management a flagship and was willing to provide resources, including specialized faculty and tuition waivers.

The more established sports management programs that offer MBAs, such as Massachusetts, Ohio and Oregon, are in college

|

Nameplates at the Lightning’s executive offices feature USF faculty.

Photo by: Enter Name Here |

towns, removed from opportunities with pro sports properties. Few schools in major sports markets offer a fully baked, dual-degree MBA/MSA. And no school is as embedded in a franchise as USF is with the Lightning.

“I wouldn’t have come here unless I thought we had a chance to do something special,” Sutton said on a recent evening, driving across the Tampa causeway to join three faculty members and six recent grads, all of whom work in sports and entertainment in the area.

Each of the 19 students in USF’s first graduating class in 2014 landed jobs in sports or entertainment. Midway through July, all but three of the 27 who graduated this year had been placed in the industry.

The gap in pay compared with their MBA counterparts entering other industries remains. Only four in the recent class will start with salaries higher than $60,000. But the low end will enter at just under $40,000, which is better than the typical starting line in sports.

“I like to say we’re a little different here,” Sutton said. “And it’s not just me marketing or recruiting. I truly believe we are.”

Lightning strikes

Not long after he purchased the Lightning in 2010, hedge fund billionaire Jeff Vinik approached USF administrators about ways that the team and school might work together. A relationship with a nearby state university would show a commitment to the region by a Sun Belt hockey franchise often rumored to be a relocation candidate. Vinik also suspected there could be a mutually beneficial exchange of opportunities and ideas.

In their initial conversations, they identified two areas of study in which they could connect: sports medicine and sports management.

“They were first and foremost looking for intellectual expertise from our faculty,” said Ralph Wilcox, the USF provost who was brought in to explore opportunities with the Lightning soon after the first contact. “And there is no question in my mind that they were looking to invest in the development of talent that might advance their business and their interests in years to come.

|

This year student Rhyan Truett’s residency will be as an assistant to Lightning President Steve Griggs.

Photo by: University of South Florida |

“They were willing to invest in a partnership. Our expectation of partnership extended far beyond their simply writing a check.”

Wilcox had a background in sports management, publishing extensively on the topic before moving into administration. He has known Sutton for 30 years. He knew that his old colleague was nearby, as associate department head of the program at the University of Central Florida in Orlando.

Once USF determined that it wanted to launch a program tied to the Lightning, Wilcox invited Sutton to lunch to discuss what that might look like, a meeting that had strong support from Lightning CEO Tod Leiweke and Griggs, both of whom had worked with Sutton on projects before.

Wilcox shared the details of what they envisioned: a partnership in which USF faculty would serve as consultants to the team, Vinik would offer his acumen and support to the school, and the Lightning would provide something akin to medical school residencies (a concept suggested by Leiweke) for grad students. Sutton became intrigued.

Sutton had helped design the sports management graduate program at Robert Morris when it became the first to move into a business school. He spent 10 years directing the graduate program at UMass. He played a significant role, along with founding director Richard Lapchick, in putting the young sports MBA program at the University of Central Florida on the map nationally.

Yet he had never seen anything quite like what Wilcox was describing.

“I came down to have lunch and get my brain picked,” Sutton said. “I didn’t have any idea I was applying for a job. But when Ralph laid it out, it was unlike anything I’d ever heard of. I said, ‘Wow, that sounds interesting.’ He jumped up and said, ‘Would you be interested?’ I said, ‘I’d be crazy if I weren’t.’ He said, ‘Great, because Steve and Todd thought you might.’”

At UCF, Sutton benefited from a close relationship with the Orlando Magic, whose owner, Rich DeVos, founded the sport business management program that bears his name. Sutton and his students worked on consulting projects with the Magic.

The team provided a steady stream of adjuncts and guest speakers.

But the opportunity in Tampa Bay was both deeper and broader. Deeper because the Lightning were funding so many project-oriented slots that would complement the students’ course work in their second year. Broader because the market had not only the Lightning but also the Rays and Buccaneers.

Sutton knew that with entering classes of 20 to 25 students, he’d need residency slots with more than just the Lightning. He knew he’d want an area of specialized study in which the school could try to become a national leader, which would turn out to be sports business analytics, leading to analytics residencies at all three pro teams and the Hard Rock.

“If you had to draw up the ideal situation for a program like this, you might put it right here, where you’ve got all these teams and a major state university,” Sutton said. “The last thing the world needs at this point is another sport management program. So if you’re going to create one, you better make it unique.”

‘Get brilliant minds cheap’

The first time that USF professor Michelle Harrolle approached the vice president of human resources at the Hard Rock about the opportunity to place MBA students there as residents, she had to graciously talk her down from her initial offer.

“She said they could take five,” said Harrolle, who manages the residency program. “I had to explain that we could only give them two.”

Turns out that USF’s residency model is appealing not only to the Lightning but also to the region’s other larger sports

|

Amanda Puccinelli, from USF’s inaugural class, chats with author and search firm executive Bob Beaudine at a lecture series.

Photo by: University of South Florida |

and entertainment employers.

“Our goal was to get brilliant minds cheap,” said JC Ayers, vice president of human resources at the Hard Rock, who in the coming academic year will host residents in analytics, marketing and international marketing, plus offer part-time work to first-year students. “To be honest, that’s what we wanted. We had lots of work that needed to be done. It was a great opportunity for us to get some important work done that we couldn’t get from a temp agency. And it gives the MBA students the opportunity to showcase their skills, which can turn into a job offer — even to the point that we’re creating a position to fit that person, which is something we’re willing to do.

“I really only had two questions. When can they start and how long can we keep them for?”

For the last two years, the Hard Rock has placed a resident in analytics, the area of study that USF hopes will help distinguish it from other programs. Casinos rely heavily on analytics, tracking the preferences and behaviors of their best customers in search of insights to get them to play more often, as well as larger trends that affect decisions such as where to put which games.

The Hard Rock residency led to a full-time analytics job at the casino for recent grad Evan Cogley. The last two students to serve as analytics residents with the Tampa Bay Bucs, Eric Holland and Bill Clark, both landed jobs in that department with the team.

The student now serving as the analytics resident at the casino, James Cifu, said he was attracted by the work opportunities and the track record of students who pursued the field landing jobs.

“Everything here is predicated on the numbers,” Cifu said. “What better way to increase your knowledge than from learning in the casino? When you come here, you see the skills you need to have in order to succeed. School is the foundation. But it takes on a whole other dimension when you get to come apply it here.”

Cifu came to USF knowing he wanted a path in analytics. But he had no idea he’d want to work in a casino until he began the placement process near the end of his first year.

The process starts with Harrolle asking employers which of their departments might be most interested in hosting a resident.

Because the Lightning has 10 slots, it typically offers opportunities across most departments. They are Harrolle’s first conversation, so she can make sure to fill the needs of the program’s largest supporter. After that, she speaks with other potential hosts about the opportunities they might offer.

In March, Harrolle distributes a list of employers and the associated job descriptions to the first-year students, asking them which they’d like to interview for and sending their résumés to those employers. She also keeps a book describing every residency thus far.

“You get an idea of what’s out there because you’re talking to the class ahead of you,” said Rhyan Truett, whose residency will be as an assistant to Griggs this year. “Then you see all the opportunities in the book. There really is a lot out there. And if you’re interested in something that’s not there, they [Harrolle and Sutton] try to find it for you.”

From there, it’s a whirlwind of matchmaking. Two years ago, Harrolle calculated that 25 students combined for 80 interviews with 15 companies in a 10-day span. After the interviews, she circles back with the employers and students looking for matches. For about 90 percent of students, those come together easily, Harrolle said, with employers asking for the same students who want to land there. For a couple each year, it takes additional work.

This, Sutton said, is where the residency model, with students working in the same market in which they study, produces one of its greatest benefits.

“It’s not like most programs, where we say, ‘See ya. Go do your internship,’” Sutton said. “We see them for two years: One year working part time and one in the internship. And if there’s anything that doesn’t work out, we’re here to fix it. The opportunity to intervene is here.”

Sutton said that has happened only once so far, with the Lightning, where a student got sideways with his boss. “I came in and said, ‘Fire him,’” Sutton said. “If he’s not what you need, fire him. … Fire him and we’ll find something else for him to do.”

The team opted not to do that, instead reducing his responsibilities and having the professors counsel him.

“The fact that the faculty is in our offices creates not only accountability but cohesion,” Griggs said. “It’s not the vice president of ticketing dealing with an intern from a sports marketing program halfway across the country. It’s Bill working with me, working with our directors, working with the residents. So it’s a full circle of interaction.”

Tackling the projects

To make sure the students are both productive and fulfilled, Sutton, Harrolle and Lightning executives work together to design each residency, typically building them around projects that lead to a specific end product. Each month, the residents meet as a group with Keith Harris, Lightning vice president of human resources, and Harrolle to discuss the progress of the projects they’re working on and to consider adjustments.

“My management team is looking at me, saying, ‘If I’m going to get this kid to manage for a year, I want to make sure it’s worth my while and worth my department’s investment,’” Harris said. “If it works out that we can offer them a job, great.

But we have so many of them, nine out of 10 are going to leave. So what did they bring while they’re here?

|

Zack Lee has used his residency at the Tampa Bay Rays to analyze data on ticket buyers.

Photo by: University of South Florida |

“Are the projects impacting our ability to sell? Are they impacting our ability to be more efficient on the operational side? Are the projects adding some creative value in our marketing? … There’s a lot of window dressing in this industry. A lot of pretty colors. That can’t be what this is. This is meant to be a real educational exercise that benefits the students and benefits us.”

The first student hired by the Lightning came from USF’s inaugural class. Amanda Puccinelli’s residency was in community relations, an area that attracted her because it married her passions for sports and community work.

When the Lightning put Puccinelli in charge of the 50-50 raffle that they held each game as a fundraiser, it was outside of what she expected her role to be. She managed a program that is far more complex than most would expect, generating about $800,000 in revenue while supervising a sales and support staff of 20.

When her residency ended, Sutton approached the team about hiring her full time, suggesting that they would be making a mistake if they let someone who was responsible for a $1 million line item as a resident walk away.

“For all I had done building the 50-50, I felt like there was still more work to be done,” Puccinelli said. “I wanted to see this through. I got attached. It became my baby. So I made that case. A week before graduation, I found out they were keeping me on.”

The three students who will serve residencies with the Tampa Bay Rays this year are returning after spending their first year working part time with the club.

Last year, two of them, Jessica Kitzmiller and Zack Lee, were assigned a project together: to pull data attached to Rays ticket buyers and analyze it to determine how they were using flex packs. Lee looked primarily at game selection to determine what beyond the obvious factors, such as opponent and day of week, influenced their selection. Kitzmiller studied demos, creating customer profiles based on gender, age and preference, along with a heat map that showed where buyers came from.

This year, they will return to the franchise — Lee to continue working on member services and ticketing, and Kitzmiller to focus on social media, where she also spent a chunk of time last year.

Both Lee and Kitzmiller pay out-of-state tuition, making the waiver and work opportunities particularly attractive.

“It’s a huge plus, especially if you’re in a situation where you’re selling it to your parents,” Lee said. “But what’s even more important to me: I’m going to have almost two years with the Rays when I get out of here. Even if I didn’t get placed with them at the end of this, I’ll walk out of here confident that the experience will be beneficial and it will get me something else in pro sports, which is where I want to be.”

Lofty ambitions

When you get past the how this comes together; the dumb luck of having an NHL owner show up at the doorstep, asking if the team and school might work together; the happenstance of geography that put a state research university in what would grow into an MLB, NFL and NHL market; the timing of that university spreading its wings to become more than the commuter school it had been for its first 50 years …

When you get past all that, you still have to get past one critical question that would be left hanging for the dean of any business school that endeavored to do that, even considering the desire and funding provided by Vinik.

Why?

|

The university and its stakeholders see the program as a way to stimulate innovation in the sports industry.

Photo by: University of South Florida |

Why would a business school want to start a sports program, considering that there are now more than 200 of them in the U.S. alone, pumping out graduates into an industry already overrun by résumés; an industry that has no established path to entry, like the management training program of the broader corporate world; an industry that generally hasn’t shown a willingness to pay more for an MBA, or even someone with a master’s degree that includes training in sports.

Though he took over as dean of the business school shortly after the program was announced, Moez Limayem has given great consideration to that very question.

“If you do the same things as the other competitors, other business schools, the same concentrations, the same majors, the same way, the best you can aspire to is to be a good business school,” said Limayem, who came to the school from the University of Arkansas. “But we want to be a world-class business school. And a world-class business school has a few flagship programs that they do better than any other business school.

“We don’t just grow programs like mushrooms or because somebody else did it. We do it because there is a need. There is a gap. And we listen to our stakeholders.”

In this case, that stakeholder was Vinik, who, along with Leiweke, recognized a need for innovation in the sports industry and saw the program as a means to stimulate that.

Behind the momentum that came from the Lightning’s support, and seed money, Sutton has built out a program that in only three years has found residencies and part-time sports or entertainment industry work for all its students, for both their years.

Driven by an understanding of where the greatest job creation has been in recent years, Sutton hired Mike Mondello, a professor who specializes in sports business analytics, to teach that area and build an annual conference. He has built a sponsor roster of teams and companies that fund scholarships and class trips, including an annual one to Los Angeles that includes time with executives from AEG and Ticketmaster, among other companies based there.

“We’re doing a lot of the things that I’ve always wanted to do,” Sutton said. “In all honesty, some of them are things that other schools do. But I don’t think that anybody does all of them. And I know nobody has what we have here with the Lightning.

“That’s pretty special.”