From a single cable channel, ESPN has evolved into a sports media giant that delivers its content to fans in every imaginable way.

To company President John Skipper, that all started with ESPN.com.

“ESPN.com really became the place where we realized we needed to be everywhere,” Skipper said. “Everything we’ve done since with mobile apps, things like Apple TV and over-the-top, what have you, optimizing for every platform, we learned how to do all that at dot-com. So many other media entities were in sort of a protect mode, not wanting to cannibalize linear with digital. But we learned to embrace it, and it rippled through the entire company.”

ESPN.com will mark its 20th anniversary this week with the release of a dramatically redesigned site after many months of development, the first major overhaul for the site since 2009. The passage of two decades online highlights the long and often circuitous journey ESPN took to reach its position as the most trafficked destination in American digital sports media.

The site began April 1, 1995, as a joint venture with Starwave Corp., a software development company owned by Microsoft founder and team owner Paul Allen, with an unveiling at the Final Four in Seattle. The effort carried the cumbersome moniker of ESPNet SportsZone, dubbed by then-NBA Commissioner David Stern as the one of the dumbest brand names ever.

SEE ALSO:

By the late 1990s, ESPN parent Walt Disney Co. bought Starwave and rebranded the site as ESPN.com. But it still stood behind CBS SportsLine, now CBSSports.com, in both traffic and overall consumer awareness, after that site forged strong early footholds in fantasy sports, original digital content and merchandising.

A Skipper-led effort in the early days of the 21st century to embrace a more magazine-style content strategy, along with a distribution deal with Microsoft to get on the

MSN portal, began to reverse the tide for ESPN.com. Video, at first on-demand and then as a live streaming product, accelerated ESPN’s emergence online. ESPN more recently has been locked in fierce battles against well-funded rivals Yahoo, NBC Sports, Fox Sports and Turner Sports for digital supremacy.

Beyond the site itself, a long series of additional ventures has helped make ESPN ubiquitous in the digital universe. The site’s founders believe the restless, pioneering spirit of the site’s early days has not been lost, even as ESPN.com sits now alone atop the digital sports media mountain.

“One of the great things is that when it moved from upstart to an incumbent among the big players in the space, it never really changed,” said Dick Glover, Funny or Die chief executive. Glover helped create what is now ESPN.com in the early to mid-1990s, and as an ESPN executive vice president negotiated the original partnership with Starwave. “It still acts like an upstart. They’re still taking risks and still growing.”

BORN IN THE DIAL-UP DAYS

When ESPN in the early 1990s began to explore its business options online, the Internet as any sort of mainstream, commercial entity barely existed. The nascent online space was dominated by services such as Prodigy, CompuServe and a then relatively unknown America Online, which provided tightly controlled offerings of digital content.

Accessing these services typically required balky, slow dial-up modems, and full-featured Web browsers had yet to be introduced. CD-ROMs carried as much, if not more, stature than any sort of online programming.

|

ESPN.com has evolved over its 20-year history and will soon do it again. From top to bottom, front pages from 1999, 2004 and 2009.

|

Glover arrived at ESPN in November 1992, hired by then-ESPN President Steve Bornstein, to head a new group called ESPN Enterprises. He was charged with identifying new areas of opportunity for the ESPN brand, with online a key priority. During that search of the digital space, Glover and ESPN turned down a potential deal with AOL in favor of one with Prodigy, driven in large part by Prodigy’s willingness to provide upfront TV ad commitments and lessen ESPN’s immediate monetary risk. ESPNet, more a licensing venture than anything else, debuted to Prodigy’s subscriber base of more than 1 million people on March 30, 1994, as largely a bare-bones service of wire feeds and bulletin boards.

The deal would be a mistake on several levels, particularly financial: By not going with AOL, ESPN passed on the opportunity to acquire warrants in the newly public company that would later be worth well into nine figures. ESPNet also existed only within Prodigy’s online walled garden, meaning nonsubscribers could not get to the content. The partnership was not renewed after Prodigy’s one-year exclusive ran out.

But the alignment allowed ESPN to keep learning and thinking about what it wanted online. Even as ESPNet launched on Prodigy, Glover kept searching for bigger and broader opportunities, and was soon introduced to Allen’s Starwave. Operating out of Seattle, Starwave was not itself a media brand and far from a household name. But it had done groundbreaking development work on CD-ROMs for the likes of rock musicians Peter Gabriel and Sting. And with the company populated by die-hard sports fans, it had also begun to create its own sports site called “Satchel

Sports,” named for legendary Negro Leagues pitcher Satchel Paige, who shared a birthday with Starwave Chief Executive Mike Slade.

“The whole concept of Starwave was to take various bets on the future of a wired world, and the first big idea I had was sports,” Slade said. “As a sports nut my whole life and a former sportswriter, the idea of an unlimited news hole and a never-ending sports page was very intriguing.”

A deal to collaborate seemed logical, since Satchel Sports would have limited opportunities for meaningful scale without any real brand recognition. ESPN, meanwhile, was constrained technically; it had only a handful of people in the company working on the Internet in any capacity, and was still years away from having a full staff of developers. But the alliance still almost never happened.

‘IN 10 MINUTES, THEY JUST GOT IT’

Geoff Reiss, then senior vice president of sports publishing for Starwave and later an executive for ESPN, the Professional Bowlers Association and Twitter, recalls

coming to New York in March 1994 for meetings with Sports Illustrated and with ESPN, and initially thinking the sports magazine giant was the logical choice for a partner.

“In those days, it was very different. SI was really the dominant national sports media brand, and in a lot of ways had a lot to offer,” Reiss said. “But that one turned out to be one of the most depressing meetings I ever had. They just didn’t want to disrupt their existing business model.”

The ESPN talks initially were more fruitful, and the companies found a deep culture match. Reiss said, “In 10 minutes, they just got it. They understood completely what we wanted to do.”

But another logistical problem soon surfaced: the name. Starwave wanted equity in the brand name in the event of an eventual divorce, and lobbied to call the new site SportsZone. ESPN wanted to migrate over the existing ESPNet, and the clumsy branding was born via compromise.

Beyond the name, though, was an enterprise poised to win. “We felt like we were really pioneering,” said Aaron LaBerge, also an initial Starwave employee and now ESPN’s chief technology officer. “We were a startup but modeled like a mature company, which made for a powerful combination.”

To that end, many of the initial components of Satchel Sports, such as in-progress scores and tree-like navigation to find content, still exist today as key elements of all digital sports media.

But if creating the site was one thing, maintaining and technically supporting it was another. In those early days, customer hardware capabilities varied wildly, and trying to write code and build features was a virtually impossible challenge.

“It was like trying build a huge jigsaw puzzle, but without the benefit of the finished picture on the box,” Reiss said. “And it’s easy to forget that people were buying and using Internet access through much less convenient [dial-up] means. But it was all very exciting, and even today I think ESPN can take pride that a sports site has played a really meaningful role in pushing the capabilities of what people can do online.”

Just a year after the launch of ESPNet SportsZone, Bornstein declared at an internal all-hands meeting that the two biggest growth areas for ESPN would be the Internet and international, heralding the importance of online to the company. It was a stark contrast to other media rivals, which for years approached online operations as a sideline or afterthought to traditional linear media.

“It sort of shocked people, what he said,” Glover said. “We were light years ahead of everybody. But it proved to be crucially important to our development.”

A NEW DIRECTION

The arrival of Skipper in January 2000 prompted a new, content-focused direction for ESPN.com. Previously the general manager for ESPN The Magazine, Skipper sought to apply many of the same concepts of quality, long-form storytelling and more arresting visuals to the website. Aided by company fixture John Walsh, ESPN.com began a furious hiring spree that would bring aboard journalistic heavyweights such as Ralph Wiley, Hunter S. Thompson and David Halberstam, plus a then-unknown Boston online columnist named Bill Simmons.

Not all of the writers stuck, and others failed to blend meaningfully into the ESPN ecosystem. Still others, like Simmons, have remained and become virtual industries unto themselves fueled by their success on ESPN.com. But beyond helping elevate ESPN.com’s brand and traffic, the overall strategy also gave rise to many specific forms of online sports journalism that are now commonplace throughout the industry, such as writers focused strictly on scoops and player transactions, statistical-based and sabermetric reporting, and columns laced with pop culture references.

Where a prior generation of sports media hopefuls nakedly copied the styles of on-air personalities such as Chris Berman and Stuart Scott, newer entrants often sought to be the next Simmons or Buster Olney.

Those varied tones were on display in several specific business initiatives on ESPN.com, such as the more lighthearted Page 2, whose influence can be seen all over the sports blogosphere, and ESPN Insider, an early source of paid, premium content that still exists today.

“It was sort of the first time the site was run by content people instead of technologists,” Skipper said.

Amid that approach, Skipper prevailed in persuading most of Starwave’s technical talent to move from Seattle to ESPN’s Bristol, Conn., headquarters after the Walt Disney Co.’s purchase of the company.

“One of the things I’m super proud about with this partnership is that even when people went from Seattle to Bristol, they kept the culture,” Slade said. “It’s made a big difference.”

Skipper’s grand ambitions were aided significantly by the arrival of broadband Internet access. The faster transfer speeds opened an array of opportunities for both programming and commerce. Ad sales were boosted by the creation of what ESPN would call The Big Unit, the primary fixed ad unit which wraps around content on the ESPN.com home page, that was a major departure from what Skipper called “the slot machine of online banner ads.”

“Everybody was doing basic click-through kind of things, but we rejected that,” he said. “The Big Unit was essentially the online equivalent of a Cover 2 [inside front cover] of a magazine.”

The new ad inventory helped elevate ESPN.com’s revenue from $23 million in 2000 to $60 million by 2002. Current site financials were not disclosed but reach well into nine figures, and digital ad sales are fully integrated into ESPN’s efforts on other platforms.

TOPPING THE CHARTS

The two key company priorities Bornstein identified in 1996 would merge as ESPN.com became a global juggernaut. A key instrument within that would be video.

Every sports fan of a certain age remembers the halting early steps of online video more than a decade ago, complete with endless buffering, dropped feeds and substandard video quality. ESPN was no exception, and video was always part of the Satchel Sports vision. But ESPN over the years continued to invest in digital video programming and deploy much of its live programming online. In 2010, it struck a large-scale deal with MLB Advanced Media to support ESPN3, its broadband online video portal previously known as ESPN360.com. ESPN3 is now housed within an even larger WatchESPN umbrella that encompasses the online and mobile distribution of nearly all of ESPN’s linear and digital networks.

The video focus now includes a collaboration with “SportsCenter” and ESPN’s TV operation that is deeper than ever and aided by the presence of Rob King, senior vice president of “SportsCenter” and news and a former editor-in-chief of ESPN.com.

“Having Rob over on ‘SportsCenter,’ and obviously knowing intimately what we do on dot-com, is immensely helpful,” said Patrick Stiegman, ESPN digital and print media vice president and editorial director. “Our belief is that ‘SportsCenter’ is not just a show but an experience, and that’s the same kind of approach we take here.”

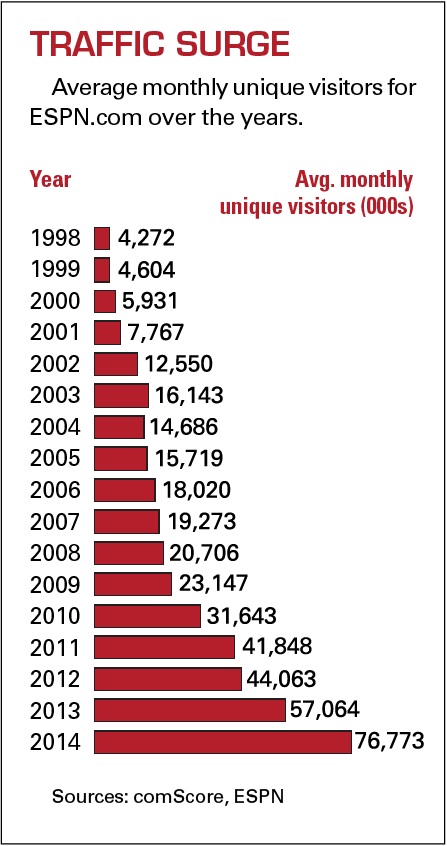

The video assets and tight integration with the rest of ESPN has also turned what had been back-and-forth digital metrics battle with the Yahoo Sports-NBC Sports alliance and others into a rout. For many years stuck in the second slot in monthly comScore rankings, ESPN has now led for the past 12 months straight, set five comScore sports category rankings in the last 18 months, and routinely reaches a global digital audience of more than 120 million people a month.

“Try to imagine life now without ESPN.com. That’s the simplest way I can put it,” said John Kosner, ESPN executive vice president of print and digital media. “So many things that we hoped would be possible have become fundamental parts of the sports fan’s experience.”