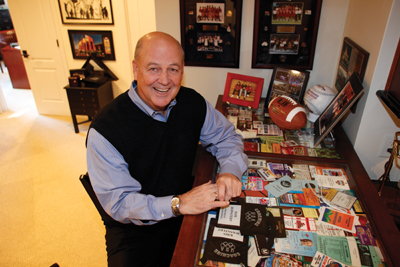

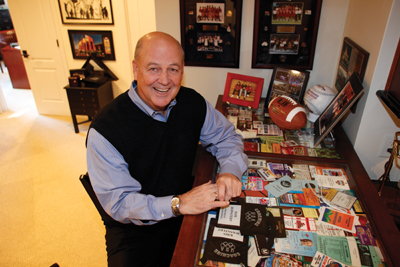

The commemorative basketballs sit in a row over the fireplace. They line a shelf over the bar. They fill bookcases and mantels throughout the den and office.

Everywhere you look in Tom Jernstedt’s basement, there are basketballs — 40 in all. The top two levels of the Jernstedts’ three-level home overlooking Indianapolis’ Canal Walk are immaculately decorated by Tom’s wife, Kris. The bottom floor, well, that’s all Tom.

There’s the basketball from John Wooden’s final game. There’s a USA Basketball keepsake from the World Championships. And too many to mention from past Final Fours that Jernstedt conducted.

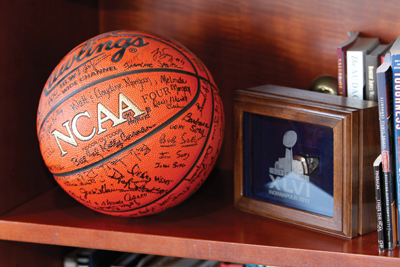

On the shelf behind his desk is a basketball signed by everyone who attended his wedding with Kris. Fittingly, they used a basketball instead of the traditional guestbook.

“I’ve never counted them before,” Jernstedt laughed, acknowledging how the number of basketballs had grown over time.

That’s what happens when you spend 38 years at the NCAA in charge of a three-week phenomenon, the men’s basketball tournament. All of those basketballs represent a professional life spent promoting and protecting the college game, all the while cultivating March Madness into this springtime spectacle.

Everything that we’ve come to know about the tournament — March Madness, Final Four, billion-dollar TV contracts, basketball in domes, brackets — can be traced to Jernstedt. He came to the NCAA in 1972 for what was supposed to be a cup of coffee and decided to stay awhile.

Practically every major development in the NCAA tournament since then happened on Jernstedt’s watch.

He was there when the Final Four moved to its Saturday-Monday finish. He was there for the first $1 million TV contract. He was there for the first $1 billion contract.

{podcast}

SBJ Podcast Archive:

From Jan. 5: Executive Editor Abraham Madkour and Champions editor Tom Stinson introduce and discuss the 2015 class of The Champions: Pioneers & Innovators in Sports Business.

He presided over big changes like the controversial tournament expansion to 64 teams and little changes like the implementation of the RPI as one of several tools to evaluate teams.

When a basketball committee member fell asleep in his chair during team selections, Jernstedt discreetly gave him a nudge. When volatile coach Bobby Knight erupted, which was often, Jernstedt was there to absorb it so others didn’t have to.

At times, Jernstedt came off as commercially conservative — he liked a clean venue without the barrage of sponsor mentions that might distract from the competition. Other friends called him a visionary for acts like shepherding the Final Four back to a dome in 1982 at the Superdome, even though the NCAA’s first experience in a dome — the 1971 Final Four in the Astrodome — had been a disaster because of bad sight lines and seats too far from the court.

During his time at the NCAA, Jernstedt was the chief administrator for several sports, as well as its COO, but basketball is what kept him there for so long despite several opportunities to become a conference commissioner or athletic director.

“Tom is the quintessential ambassador for college sports,” said Greg Shaheen, who worked shoulder-to-shoulder with Jernstedt at the NCAA.

“We would not have a Final Four as we know it without Tom,” said Jim Host, his longtime friend and NCAA marketer. “No one else impacted the tournament or college basketball the way Tom did.”

Jernstedt spent his summers as a youth picking berries and beans. It’s just what you did growing up in Carlton, Ore. Hopping in the back of a pickup truck and riding off to the fields became a rite of passage for the teens from Yamhill Carlton High School, long before travel baseball and football camps filled summer calendars.

“Everybody wanted to go because that’s where your friends were,” Jernstedt said. “It was also a good chance to make money. On a good day of picking berries and beans, you could come home with $3 in your pocket.”

Carlton, population 1,054 at the time, was a small farming and logging community between Portland and the Oregon coast. Even though the consolidated high school merged the two nearby towns, it was still small enough for a pretty good athlete like Jernstedt to emerge as a star in three sports.

|

Tom Jernstedt’s basement reflects his 38 years of promoting and protecting the NCAA basketball tournament, including being decorated with 40 basketballs from some of the game’s biggest stages and greatest moments.

Photos by: TOM STRATTMAN

|

Jernstedt played football, basketball and baseball in the days before obtuse coaches started demanding that kids specialize in one sport. And he played them pretty well, despite a foot that didn’t always cooperate.

At age 6, Jernstedt contracted polio, which put him in the hospital in Portland. This was in the early 1950s, just a few years before the polio vaccine was widely available. But Jernstedt said he was lucky. He described it as a mild case of polio that doctors caught early and were able to treat.

Even now, Jernstedt doesn’t walk

with the normal heel-to-toe motion, although many of his friends never knew what he had to overcome.

Still, by the time Jernstedt was a teen, he was a three-sport standout. He was all-league in basketball, and in baseball he threw four no-hitters. A lead in the local newspaper, The News-Register in McMinnville, in 1963 read, “Everything he does is great!”

But, contrary to his professional life dominated by basketball, Jernstedt excelled at football. Despite commitments at various times to play quarterback for Houston and then Washington, Jernstedt, a left-hander, wound up at the University of Oregon.

“Tom had this very meticulous way about him, even in how he put on his uniform,” said Terry Shea, an Oregon teammate and, like Jernstedt, a quarterback. “He was highly respected throughout the team and he became, in his own country way, a player with some stature and leadership. That’s hard to do if you’re not a star.”

Neither Jernstedt nor Shea could break into the lineup, so they often found themselves sitting next to each other on the bench. Sometimes they’d rub mud on their uniforms so that they looked like they’d played.

“We’d sit there on the bench and compare how many passes we completed in pregame warmups,” Shea said with a laugh. “We had to keep ourselves occupied.”

Jernstedt, from his spot deep on the Ducks’ roster, still managed to make an impression on Oregon’s coach, Len Casanova, who helped launch the coaching careers of future greats George Seifert, John McKay and John Robinson from the Eugene campus.

“By the end of my sophomore season at Oregon, I could see the end of the line athletically, and I never wanted to be perceived as a dumb jock,” Jernstedt said. “I got involved in student government.”

Jernstedt became senior class president at Oregon and briefly contemplated a career in politics.

A few years later, after a stint in sales, Jernstedt returned to his alma mater to run events for the Ducks. Casanova, his former coach who became athletic director, never forgot the quarterback at the end of the bench. Jernstedt left a job selling coffee for McCormick in Northern California for $12,000 a year and a company car, to make $6,000 a year at Oregon.

“I couldn’t get there quick enough,” he said, recalling his desire to get out of sales, despite the pay cut.

The turning point for Jernstedt’s career in athletic administration came in the spring of 1972, when he helped run the NCAA track and field championships at Oregon. The night before the competition was about to begin, the chairman of the NCAA’s track committee, a Kansas State coach named DeLoss Dodds, informed Jernstedt that there was a problem. The intervals for the mile relay were marked incorrectly.

This information, of course, had to be relayed to the Ducks’ track coach, Bill Bowerman. By this time in his career, Bowerman, a former Army major, had won four NCAA championships and was among the most decorated track coaches in the nation. Charges against the man or his track were not to be taken lightly.

Jernstedt, upon delivering the news of the mismarked intervals to the intimidating and sometimes prickly coach, was told there’s no way the track had been measured incorrectly and refused to make changes.

Under the cover of darkness, though, Jernstedt went into Hayward Field and made the adjustments to avoid any embarrassing moments. To this day, being caught between Dodds, the future powerful AD at Texas, and the legendary Bowerman, who co-founded Nike with Phil Knight, remains “one of the most stressful situations I’ve ever been involved in.”

Jernstedt goes by many names.

Father of the Final Four.

Most influential man in college basketball.

The Billion-Dollar Man.

The Architect.

Any of them seem appropriate now. But in 1972, when Jernstedt left Oregon to join the NCAA as director of events, the Final Four wasn’t even known as the Final Four.

Jernstedt received the job offer from the NCAA largely because of how he handled the track snafu that spring. He figured he’d stay three years or so, make a broad range of contacts and then go do what he’d always wanted to do — become an athletic director.

But there was something about the first NCAA tournament he ran in 1973 that got into his blood. His initial championship, with the semifinals and final at the Checkerdome in St. Louis, offered a taste of everything to come.

Bill Walton was spectacular, scoring 44 points in the final on 21 of 22 shooting. UCLA won another title. Wooden was classy. Bobby Knight, in his first Final Four, bitched about everything. And then there was Providence coach Dave Gavitt, who went on to found the Big East and become one of Jernstedt’s closest friends. They talked on the phone before the semifinals. They talked in St. Louis. They hit it off that weekend, fast friends who shared a love of basketball.

|

Under glass on a bar in Jernstedt’s basement are credentials and tickets from his decades working in sports.

Photo by: TOM STRATTMAN |

Jernstedt was struck by how important the tournament was to the coaches, the players and the fans. That feeling never left him for the next 37 years. He committed himself to make it the best experience it could be for the participants, modeling his approach after the Masters.

“A lot of times, things can grow too fast or too slow. The NCAA tournament grew very organically,” said Big Ten Commissioner Jim Delany, who worked with Jernstedt at the NCAA in the 1970s and remains a close friend. “Tom is the guy who nurtured it. He was open to change, but he never forced it. … Tom built the culture; he’s been the one constant.”

“Whatever the tournament is today, Tom made it that way,” Big 12 Commissioner Bob Bowlsby said. “His fingerprints are everywhere.”

Jernstedt’s oversight of the tournament can be traced to every corner of its existence, from the TV negotiations to the men’s basketball committee and the selection process. Those are all well-chronicled.

Jernstedt’s genius, says Bill Hancock, executive director of the College Football Playoff, is in the details. Much of what Hancock learned in his 15 years working alongside Jernstedt at the NCAA shaped the CFP’s selection process.

During one of the first CFP selection committee meetings, Hancock had the idea of giving the committee members a hat with their name on it. Then, as they entered the meeting room, they were instructed to take off the hat and hang it on a rack. It was a symbolic gesture to remind members that they must check their agenda at the door.

It was the same message Jernstedt preached to the basketball committee for nearly 40 years.

“The tournament became an event that’s unassailable. It’s classy, dignified. It’s everything that Tom is,” Hancock said. “He insisted on everything being done right. No corners were cut for any kind of administrative convenience. If it meant spending a few more hours at the office to do something the right way, so be it.”

In-venue signage was covered during the NCAA tournament. Soda cans weren’t allowed courtside because Jernstedt didn’t like the way they looked.

From one site to another, even in the early rounds, there was a consistent look and feel to the tournament. Whether the event was in Syracuse or Greensboro, Jernstedt demanded that the operations remain the same.

Even year-to-year, Jernstedt impressed upon Final Four bidders that substance would win out over splash. He didn’t want Final Four sites trying to outdo one another.

“Tom wasn’t looking for new benchmarks every year,” Hancock said. “He didn’t want an arms race among Final Four hosts. He thought it could be devastating. He thought the tournament should have a certain dignity and consistency about it.

“Tom wanted it to be more like the Masters, not a NASCAR race.”

The end came swiftly and unexpectedly.

In an email dated Aug. 13, 2010 — Friday the 13th — Jernstedt started with alarming news.

“Dear Colleagues and Friends,” he wrote. “This morning I am sentimental about the information I want to share with a small group of you. Shortly there will be an official announcement of my departure from the NCAA.”

Days earlier, new NCAA President Mark Emmert, who wasn’t supposed to officially start for another two months, informed Jernstedt that his position was being eliminated. Amid restructuring and consolidation of the senior staff, Jernstedt was out.

In his typically meticulous attention to detail, Jernstedt made handwritten notes about the meeting that led to his departure. In fact, it wasn’t a meeting at all. It was a phone call.

From the notes he made that day, 4½ years ago, Jernstedt shared how it all went down.

In the weeks preceding his notice, Jernstedt flew to Los Angeles to meet with the new NCAA president. They had a three-hour dinner that Jernstedt described as “very enjoyable. We fired questions at each other.”

|

Jernstedt, shown with his wife, Kris, and son Cole, 12, in their Indianapolis home, keeps a presence in college athletics by consulting with the Big East and serving on the CFP selection committee. BELOW: For their wedding, guests signed a basketball instead of the traditional guestbook.

Photos by: TOM STRATTMAN

|

On a Sunday afternoon, Jernstedt received an email from Emmert to set up a 5 p.m. call the next day. Jernstedt prepared notes so he’d be ready because he had no idea what was coming.

Minutes before the call, Jernstedt walked down the hall inside the NCAA’s Indianapolis headquarters to a conference room. Jim Isch, the NCAA’s interim president, knocked on the door unexpectedly to join the call.

“That’s when I knew something was going on,” Jernstedt said. “It was awkward. I was starting to read the tea leaves.”

Emmert delivered the news that he planned to restructure the senior staff and that Jernstedt’s job would be consolidated with others. The call lasted two minutes and it was done. Jernstedt’s only comment to Emmert was that he thought this should have been handled in person. He figured he’d earned that much in 38 years.

Jernstedt called his close pal Host, who lived three hours away in Lexington, Ky., to share the news.

Host said simply, “Tom, I’m on my way.”

Host and his wife, Pat, drove to Indianapolis that night to console Jernstedt and Kris. They spent the night in the Jernstedts’ basement, surrounded by basketballs, telling stories.

The rest of the email was pure Jernstedt. Despite his shock, Jernstedt actually supported Emmert’s decision to select his own staff.

“Thank you for helping to make my career at the NCAA a true highlight of my life,” Jernstedt concluded in the email to his friends.

In a 24-paragraph NCAA press release later that month, Jernstedt’s ouster was unceremoniously detailed in the 23rd paragraph.

Six months earlier, in a strange twist of timing, the National College Basketball Hall of Fame had announced that Jernstedt would be inducted.

Saturday afternoons haven’t changed all that much in the four-plus years since Jernstedt, 70, departed the NCAA. The three televisions in the basement, where he watches games with his son, 12-year-old Cole, are still tuned to college basketball, each on a different game.

As a consultant, he has worked with the Big East’s coaches and administrators to organize a league from scratch.

“When I got the job,” said Big East Commissioner Val Ackerman, “one of my first calls went to Tom. I said, ‘Tom, I need help.’ He’s been like a Swiss Army knife for us.”

In a couple of weeks, the Final Four will return to Indianapolis and Jernstedt will sit in the stands of Lucas Oil Stadium with his immediate family, including the two children from his previous marriage.

It’s a long way from the courtside seat he occupied for 38 years.

But for those running the tournament, Jernstedt won’t be far away. His fingerprints will be everywhere.

“Tom’s impact is everlasting,” said John Wildhack, ESPN’s executive vice president for programming and production. “He represented the NCAA beautifully.”