Television host Vernon Kay is often asked why, if his looks are so critical, he risks facial injury playing amateur football.

Most Americans, weaned on the sport, might sympathize with his refusal to punt his pigskin passion. Kay, however, is English, a United Kingdom media celebrity, a defensive back for the London Warriors of the British American Football Association league, and a Johnny Appleseed of sorts for the NFL who owns 32 team caps.

“People always say to me, ‘Do you not worry that you will get injured,’ because you see, I host ‘Family Feud,’ ” said Kay, 40, seated earlier this summer in his favorite London pub where he watches NFL games, a World Cup match distracting above the bar.

To grasp just how striking the NFL’s U.K. strategy is, with a healthy chance London gets a team before Los Angeles, consider the cultural confoundment Kay creates pulling on shoulder pads. American football, while growing in the U.K., is hardly native to British soil. (Some joke it’s one of the few sports the English don’t claim to have invented.) Kay’s family and friends, he said, called him weird in his youth for throwing a football around, and not much has changed in the years since: Secondary schools do not offer American football.

|

Pregame ceremonies get underway at Wembley Stadium prior to last year’s game between Jacksonville and San Francisco.

Photo by: Getty Images |

“In terms of engaging a nation to buy into a sport,” said Chris Kermode, a long-tenured British sports executive who now runs the ATP World Tour, “you have to be able to play the game, or take part in it.”

But the NFL is brashly challenging the paradigm that people must either have played a sport, or know those who have, to follow and engage in the action. In 2002, a quarter-million English watched the Super Bowl. Last year, following a decade of NFL marketing investment, the number sniffed 4 million for a game that starts locally at 11:30 p.m.

This fall, for the first time, the league will play three regular-season games in London, with the Jacksonville Jaguars slated to contest one of their eight home games annually in London through 2016.

Surely, some of the interest in London comes from expats and Brits who lived in the States, but they make up only one-quarter of U.K. NFL fans, according to research conducted for SportsBusiness Journal by Turnkey Intelligence (see survey highlights).

The NFL needs native Brits if it’s to win this international gamble. And the stakes are high. Dominant in the U.S. sports market, the NFL envisions international, and the U.K. in particular, as its next big growth area.

Talk is rampant in league circles that the number of London games will increase again in 2015, with a permanent team not far behind, making the NFL the first major league to expand overseas.

“It’s a question of time before we see real globalization of the biggest leagues,” said Yanni Andreopoulos, director of AEG Sports Europe in London, considering the prospects of intercontinental league. “Whoever cracks it and makes it happen will be in a great position.”

Circus or true fans?

There’s little debating that the eight NFL games played since 2007 at the modern Wembley Stadium have been game-day successes — smashing, as they say in London. The games have sold out the stadium’s 84,000 seats in days. The atmosphere has been festive, and a promotion last year that featured a football carnival on the busy thoroughfare Regent Street attracted half a million people and even won an award from a local sports business group.

“I have been involved in U.K. [soccer] for 25 years and I have never experienced such a well-run event,” said Terry Byrne, David Beckham’s former agent and a soccer marketer, of the NFL International Series games, as the Wembley contests are known. “It was a very slick, well-organized operation.”

Similar accolades echo throughout London — notwithstanding whether the person has a positive or negative stance

|

As part of the International Series, London shuts down Regent Street for an NFL block party.

Photo by: USA Today Sports |

on the NFL’s U.K. prospects — because what they’re really opining on is event production and not necessarily the sport’s popularity. The U.K. bar is not set high for what constitutes a well-run event. Dominated by soccer, British sports significantly trail American ones in how they treat fans, with little concept of a fan experience beyond the field of play. But that is changing, and the NFL is affecting that shift.

“People don’t want to stand anymore in a freezing terrace battered by the elements and have a lousy E. coli burger,” said Nick Wright, a British pollster with Luntz Global, the American firm helmed by political and cultural opinion leader Frank Luntz.

The NFL, featuring pregame and halftime shows, cheerleaders, and the entertainment mix the league excels at, is now part of the must-attend British sporting calendar, alongside brands like Ascot and Wimbledon.

The question often asked in London, based on interviews with more than two dozen opinion leaders and insiders, is whether the NFL’s Wembley attendees are going for football or for spectacle? And, if the NFL is a spectacle, can the league find the fan passion necessary to support a team?

“The NFL feels like kind of a novelty act,” said Carsten Thode, director of consulting at Synergy Sponsorship, a British sports marketing firm. “It is a little bit manufactured. Not to say that is a bad thing; they need to manufacture it.

“Look at the guys sponsoring the NFL at the moment. It is Visa, Pepsi Max, Budweiser — the story is the same,” he continued. “It is kind of American brands spreading American culture, spreading the American lifestyle.”

When Synergy asks U.K. and European companies about the NFL, Thode said the response is, “It is too niche and too American.”

“Stuff needs to happen first before it becomes something that European brands see as a powerful opportunity to connect to their audience,” he said.

Even Kay wonders why the NFL often markets the game on the backs of cheerleaders, urging the league to bring more players over for promotional appearances.

“We see it as those crazy Americans,” Kay said, laughing in his telling of when cheerleaders arrive. “There are the dancing girls.”

Betting on the future

If there is a U.K. pied piper for the NFL, it’s Alistair Kirkwood, an amiable Englishman who manages the NFL’s 15-person London office.

In 1998, he graduated from college in the Netherlands and sent a letter to then-head of NFL International Bill Peterson, who currently runs the North American Soccer League. Kirkwood wrote about all the ways the NFL botched its European push and why the league should hire him.

|

Team-branded scarves are sold in a nod to London’s soccer culture.

Photo by: Getty Images |

“It was rude but effective,” Kirkwood said of the missive, which got him in the door (although he conceded his collegiate policy prescriptions were naïve.)

Kirkwood arrived at a time when the U.K.’s best days embracing American football seemed finished. The NFL enjoyed a brief England heyday in the mid-1980s, when an upstart broadcast channel, 4, carried the sport to distinguish itself. Interest boomed, and the league expanded to London through the World League of American Football, the defunct NFL Europe’s predecessor. Many of today’s middle-age U.K. fans got their first taste of the sport and never lost it. Interest, though, quickly waned. Channel 4 dropped the sport, and the NFL pulled back.

What the NFL spent overseas it sprinkled ineffectively over the money-losing European league, which the NFL mercifully euthanized in 2007.

Meanwhile, soccer, beset by fan tragedies and disharmony in the 1980s, got its act together with the formation of the English Premier League in 1991. By the time the NFL hired Kirkwood to work in London in the late 1990s, the league’s focus lay elsewhere. To suggest then that a decade and half later the league could locate a team in the country would undoubtedly have been treated as sheer lunacy.

Kirkwood, as it turned out, needed to gamble his employment to get the NFL’s attention.

In 2002, he sat in New York NFL headquarters across a conference room table from then-Chief Operating Officer Roger Goodell, who four years later ascended to commissioner. Kirkwood wanted to recapture the enthusiasm of the 1980s and flew to New York to press the case for more investment from the mothership. The immediate goal was to increase the Super Bowl’s slim quarter-million viewership.

“Roger asked a few questions about what the metrics would be for success,” Kirkwood recalled of the meeting, which may well be remembered for launching a U.K. franchise. “I said, ‘A million viewers.’ When I asked him about this anecdote three years ago, he didn’t recall it — probably because he’s done this type of thing plenty of times before.

“At the end of the [slide] deck, and there are 12 other people in the room, he turned around and said, ‘Do you really believe in this?’” Kirkwood recounted. “And I said, ‘Yeah, passionately.’ ‘So if it doesn’t work out, you don’t hit your metric, would you resign?’ There is only one answer to that. ‘Of course I would.’ And he goes, ‘OK, go ahead and do it.’ He walks out of the room, and I am going, ‘What’s my metric? What are my chances of getting this done?’”

The official Super Bowl U.K. viewing number in 2003, aided by new broadcast coverage, topped the 1 million target by 34,000 viewers. Kirkwood figured the number, because of the small viewer sample size, could have formally fallen below 1 million with but a handful of fewer TV sets tuned to the game.

“My guess is if we hadn’t met the metric we wouldn’t have gone any further,” he said.

Three million avid NFL U.K. fans?

To get permission to drive a taxi in London, drivers are required to learn upward of 25,000 street names. That’s hardly surprising to anyone who has wandered the moniker-strewn streets, each name seemingly signifying centuries of history — and none of which is remotely connected to American football.

|

The NFL’s stepped-up production at Wembley Stadium also includes musical acts.

Photo by: Getty Images |

Two hundred and seventy tube stations dot the city. There are more than a dozen professional soccer teams. And, if the NFL is correct, in London and across the U.K., there are 3 million avid NFL fans.

The league, citing polling and research conducted out of New York, estimated that the number of avid fans has risen 200 percent since 2009, and pegged the number of casual fans at 14 million, which is 22 percent of the U.K.’s population.

Those figures are not without doubters.

“I would say there are 3 million rugby fans in the U.K. The NFL: I would doubt it is close to half a million,” said British music magnate Chris Wright, who founded Chrysalis Records and once owned teams in the English Premier League and local rugby and basketball leagues.

Added Steve Martin, global CEO of M&C Saatchi Sport & Entertainment, “The 3 million figure is an awful lot. There are 60 million people here; 3 million is pretty high.”

There is certainly an avid core, culled from the 1980s and the NFL’s latest push. And people are watching. Sky’s broadcast of NFL games Sunday evenings, which constitute about 5 percent of its total programming, usually top the ratings for those hours, averaging about 600,000 viewers.

“Personally, where I live, there are more fans of the NFL than tennis or cricket,” said Jozef Vincent, 32, who runs the Jaguars’ U.K. fan organization from his home in a small town in Wales, several hours outside of London. “I get approached by new fans all the time who want to know how the NFL works. It’s different with free agency and the draft process, which is alien to our sports.”

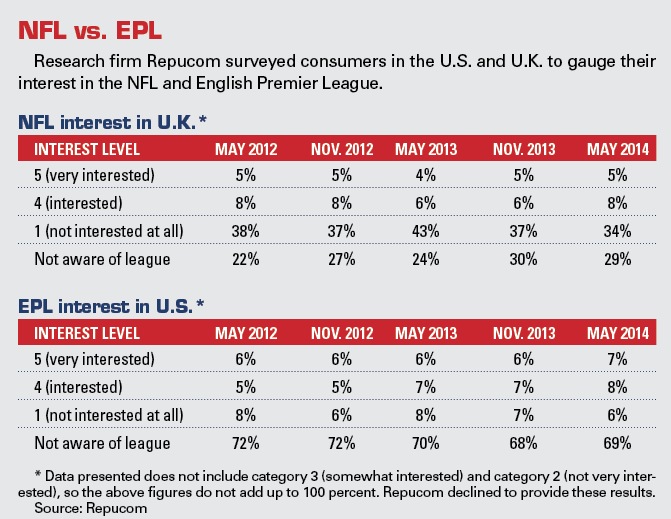

According to sports evaluation and polling firm Repucom, Vincent’s experiences are not uncommon. Five percent of the respondents to a May 2014 U.K. Repucom poll said they are very interested in the NFL. That mark is equivalent to the percentage the NFL contends are avid fans.

NFL growth is slowing, however, according to Repucom, whose poll size is 1,000 people. The “very interested” figure has remained constant since Repucom in May 2012 began polling interest in the NFL, and the respondents who report they are not interested or have no awareness of the NFL has increased over the past the two years, from 60 percent to 63 percent, according to Repucom.

The NFL’s Kirkwood has heard all this before and is unconcerned. In two or three years, he expects the number of avid fans to grow 50 percent, to 4.5 million, the threshold the NFL considers necessary to ready the next big move in the country.

“Then we are in a state,” he said, “where we have got some interesting options.”

Sizing up loyalties among fans

Presuming 3 million is the number of avid U.K. fans, is the NFL wrong nonetheless to use that as a metric for deciding whether to bring a team?

Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones last year in an interview with SportsBusiness Journal predicted a franchise in London within five years, saying, “It is logical to think once you establish a team there you will get that most important part, to me [of sport] … a little syndrome called, My Town Beating Your Town. My city one-upping your city. At the end of the day, when we play the Giants or we play Washington, that is Dallas against New York, or Dallas against Washington.

“London can catch on and want to see London beating the Giants. That is the ingredient there,” he said.

But that assessment doesn’t square with the established culture of British sports, where annually up to half the EPL teams are in London, and none has London in its name. The biggest game of the year in Manchester is when the two local EPL teams square off, not with a London entry. The British in fact have their own term, derby (pronounced “darby”) to describe a game between intracity rivals.

Wright, the music executive, described as his biggest regret in owning the London Sharks of the British Basketball League the decision he made to insert the city name into the club’s moniker.

“There has always been a problem with having a London anything,” he said. “People in London don’t gravitate toward supporting a team because it is a London team.”

There is another problem for the NFL if fans are to root for a London franchise: Avid U.K. American football adherents root for existing teams. Their loyalties are claimed.

“Everyone’s picked their teams already,” said Shaun White, a Denver Broncos fan and Londoner who is also head of European marketing for Electronic Arts. “Will people associate with a London team, or will they stick with those they have supported throughout the years? Or will it be mixed?”

One of the more unusual aspects of the Wembley games is that all 32 team jerseys are represented in the stands, with fans of every team at the contest.

“It’s bizarre,” said Synergy’s Thode, a Bears fan who lived in Chicago during the team’s mid-1980s heyday.

It could take a decade from placing a team in London to creating a true NFL team following, Thode predicted. “The NFL,” he said, “has to be realistic.”

Grassroots push

When Aden Durde, a Middlesex, U.K., native, played for the Hamburg club of the old NFL Europe in 2006, an American teammate at the season’s close told him he was off to rent a car. Laughing hard at the memory, Durde recalled he asked his teammate, whom he wouldn’t identify, why. The teammate responded, “I am driving home.”

Speaking from Dallas Cowboys training camp in Oxnard, Calif., where he interned as a defensive back coach for the summer, Durde said he broke the news softy to his burly friend that there is an ocean in the way.

If the NFL is going to overcome the obvious cultural dissonance between its unique place in America and the U.K., men like Durde should help. He coaches the amateur London Warriors and is eager to become the first Englishman to coach in the NFL. If he were to succeed, he could serve as an inspiration for British youth, who might in turn follow a team.

Durde and his friend Kay, the TV host, hammer at the point that the NFL must do more to invest in the game at the lower levels. Kay sent the NFL a proposal to develop a youth academy, the kind individual soccer teams manage throughout Europe.

“They come, they pitch the tent, we buy the tickets, we buy the shirts, we drink the Budweiser, we consume everything that surrounds the NFL,” Kay said. “Mine is not an issue. I would like to see some grassroots investment by the NFL.”

There is progress. The game is now played at 75 universities. Equipment sales are rising, though still only through specialty retailers and not in traditional sporting goods stores. And the NFL has invested a bit in grassroots, with the Jaguars doing their part as well.

But the NFL is geared to promote the NFL and not necessarily youth football. The league hypes the games and offseason player and cheerleader appearances, which promote the league and the team brands.

“We are not there to govern the sport. We are there to grow the NFL,” said Chris Parsons, the former NFL senior vice president of international, speaking shortly before he left his post this summer.

Investment in grassroots would send the message that the NFL is serious this time, said Martin, the M&C Saatchi CEO. The NFL jumped ship after the 1980s and then folded NFL Europe, he recounted.

“Is this a publicity stunt to build a licensing platform, or is there a long-term grassroots approach?” he asked. “People aren’t stupid here. They don’t forget.”

The NFL has other hurdles. Soccer is a compact, 90-minute game with a 15-minute intermission, consuming maybe three hours of someone’s day. NFL fans often spend two to three times that with their team on game day. The stop and start of the NFL game is also foreign to the continuous play of most U.K. sports.

Of course, that is a chance to market and sell, said Alastair Campbell, a political consultant and a former adviser to Prime Minister Tony Blair.

“[Low] level of knowledge and experience is an opportunity,” he said. “One of the things that is changing in sports is people love data and facts, and to chew over things that are happening in the game.”

Laura Oakes knows the NFL will never overcome soccer. The Jaguars’ U.K. sponsorship director, who worked in traditional British sports ranging from cricket and horse racing before the Jags hired her last year, is sure of one thing: While the NFL today is likely a top-six or -seven sport, trailing Formula One, rugby, cricket and golf, that pyramid is already inverting.

Seated in a coffee shop across the street from the NFL’s U.K. office, just around the corner from where the league shut down Regent Street for its fan fest, an unprecedented action in London for such an event, Oakes spoke with an unmistakable air of confidence.

“We won’t win the war against soccer,” she said, “but we will against every other sport.”

What they're saying

Eric Baker, CEO of Viagogo: “Could you put a local team in London and sell out eight games? They may be able to do that. … In the U.K., American football is much more popular than basketball ....”

Alastair Campbell, political consultant, former adviser to Tony Blair: “The fan base is obviously there, they are through the door, the interest is there. … I think it would work.”

Nick Wright, Luntz Global: “It lacks a figurehead, a personality at the moment. It is ‘American football,’ and as long as you call it that you are always on the back foot.”

Jozef Vincent, president of Union Jax boosters club: “I would rather see different teams play here rather than a [permanent team]. The NFL fan base is not just a London fan base.”

Steve Martin, CEO, M&C Saatchi Sport & Entertainment: “The smart play would be six to eight games featuring different teams.”

Alistair Kirkwood, managing director, NFL UK: “This is a long journey. This is a game that hasn’t been played as an individual sport … for the most part it is not an Englishman’s sport. It is an incredibly competitive sports landscape, and if you are trying to get a share of the hearts and minds, you have to come in with a sense of credibility and a sense of being very fan friendly.”

Carsten Thode, director of consulting, Synergy Sponsorship: “If there is a London team, it wouldn’t have a massive fan base to start with. Even if 3 million fans love the NFL, they love other teams.”

Yanni Andreopoulos, head of AEG Sports Europe: “Wembley can be a tough sell. The reality is no one would touch Wembley unless it was a really big event. The fact the NFL went in there and has been selling out every year since they went in there, that is impressive. Especially starting from a position of obscurity. You don’t even get 80,000 at Wembley for all of England [national soccer] games.”

Chris Wright, founder of music company Chrysalis and former U.K. sports team owner: “When you get outside of the U.S. you are living in a one-dimensional sports world. Maybe not so in every country, but in England if you pick up a tabloid paper, the first eight pages are soccer. … You need to develop superstars more. NFL players are not always the most interesting people; they can be very vanilla. The quarterback for the Denver Broncos is pretty boring. He is not very interesting, yet the Super Bowl was all about him. He was not going to make some young kid say, ‘Hey, I want to grow up to be Peyton Manning.’”

Fredda Hurwitz, global vice president, strategic planning, marketing and communication, Havas Sports & Entertainment: “Having a franchise is a statement, a statement of intent, ‘We are not going anywhere.’ People aren’t going to say no to that.”

Chris Kermode, ATP Tour president: “At the moment the NFL games have been hugely supported, so successful, but people are going for a sports event, and the demand for sport events is huge. But they are one-off events. But in terms of engaging with a nation to buy into a sport, it is a long-term project.”

NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell (Sky Sports interview, July 29): “There were skeptics [in 2007 when the first regular-season game was played] even among our teams. Is this a novelty or is this really passionate support? And what we have proven is this is really passionate support. … It is realistic to think a franchise could be here.”

— Compiled by Daniel Kaplan