The 18-wheelers arrived on a Tuesday night. They rolled into Stewart-Haas Racing’s Kannapolis, N.C., headquarters 48 hours after the Toyota/Save Mart 350 in Sonoma, Calif.

Dusty. Dirty. Well-traveled. Full of everything a team needs for a NASCAR Sprint Cup race weekend.

In less than 24 hours they’ll depart again. They’ll be clean, pristine and newly organized. Completely restocked, full of everything a team needs for another race weekend.

|

|

Kevin Harvick’s pit crew at work at Kentucky Speedway

Photo by: AP IMAGES

|

The drivers parked the four trucks at the back of the Stewart-Haas building and started to unload them. Out came the toolbox. The Coca-Cola cooler. Cars. Gears. Suspensions. Decals. A-frames. Firesuits. Almost nothing from Sonoma, a road course, can go to the next NASCAR Sprint Cup race at Kentucky Speedway, an intermediate racetrack. Only chemicals and tape are left on the trucks.

The next morning Ken Gober shows up to reload the No. 14 truck before he drives it to Kentucky that afternoon. He and the team have six hours to reload the truck. The team’s firesuits for the Kentucky race aren’t even at the shop yet. The dry cleaner, which Stewart-Haas pays $2,400 per weekend, delivers them around noon, and they are among the last things loaded into the truck.

“It’s a whole redo, and we don’t have a lot of time on these short weeks,” said Gober, who drives the truck that hauls Tony Stewart’s No. 14 car.

Less than 24 hours after the team’s trucks returned from Sonoma, they are on their way to the Saturday race in Sparta, Ky. It’s all part of the weekly routine at Stewart-Haas Racing, or any other NASCAR team, for that matter.

Most people know that NASCAR is a traveling circus, a weekly carnival built on rubber and exhaust. But outside of motorsports, few can appreciate everything that goes into creating that big top each week. During a season, the sport travels 38 weekends across 23 markets, and that doesn’t include test sessions. Teams truck race cars and parts, fly dozens of people and set up temporary homes at all of them.

The NASCAR schedule makes the logistics and costs of operating a race team unique in professional sports. While stick-and-ball teams have front-office staff, players and administrators, NASCAR teams have pilots, flight attendants, long-haul truckers, engineers, mechanics, even chefs. Outside of racing, few — if any — face such a challenge of coordinating freight trucking and airline travel across so many weeks.

Doing so is an enormous undertaking that takes months of planning. The Kentucky race weekend highlighted just how demanding it can be.

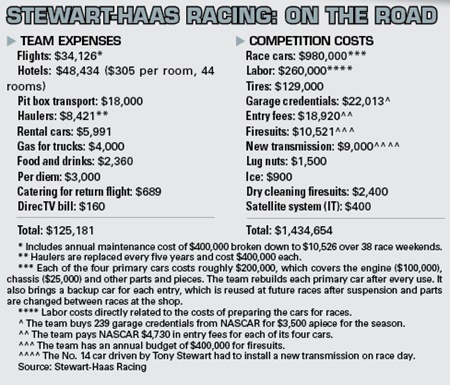

Over the course of three days in June, Stewart-Haas Racing trucked eight race cars and flew more than 100 people to Kentucky for the Quaker State 400. It rented 27 vehicles and reserved 44 hotel rooms. It spent more than $1.5 million (see chart below), and its four entries finished seventh, 11th, 12th and 21st to collect a combined purse of $428,401. (That doesn’t include driver salaries or additional personnel costs.)

As teams prepare to head to Indianapolis for NASCAR’s annual Brickyard race, last month’s Kentucky race provided a glimpse at what goes into a typical race weekend, how it comes together and how much it costs.

“It’s totally different from anything else in sports,” said Steve Lauletta, Chip Ganassi Racing president. “Chip says all the time that people turn the TV on Sunday and see the flyover and the drivers strapping in. They watch for 3 1/2 hours, but most have no idea what it took to get there. All the work. All the people. All the travel. There’s so much that goes into it, and it’s always changing.”

DAY ONE

Concord (N.C.) Regional Airport is all about racing. The carpet features crossing checkered flags. Prints by NASCAR artist Sam Bass line the walls.

More than 80 percent of the airport’s traffic is NASCAR-related, and on Thursday morning at 7 a.m., the place is filled with crew members in red polo shirts with BK Racing logos. The smaller NASCAR team has chartered a plane for the Kentucky race and must wait until everyone arrives before they board it.

The Stewart-Haas employees breeze past BK Racing crew members and down the tarmac to the team’s private plane. There’s no airport security. No laptop or carry-on four-ounce toiletry inspection. There’s just an asphalt walkway to the plane where a flight attendant, who works for the team, checks their IDs.

Stewart-Haas is one of a half-dozen NASCAR teams that have their own plane. Teams moved to private air travel in the 1990s because it gave them the ability to limit the time employees spent traveling. It also gave the team the flexibility to manage travel for staff if unexpected issues delay or postpone a race.

Stewart-Haas owns two planes that cost $11 million each. One flies up three days before the race with the crews that work on the cars. The other flies up the day of the race with the pit crews.

The planes last for 10 years and require $400,000 in annual maintenance. But the $3,000 an hour it costs to fly them to a race is still cheaper than chartering flights to and from the race. Stewart-Haas learned that firsthand when it expanded to four teams this year. It doesn’t have enough space on its 50-seat plane to fly the fourth team up and each week has to reserve eight seats for $6,000 on ConSeaAir, a company that flies to every NASCAR race from Concord.

|

|

Stewart-Haas’ Kentucky weekend was a whirlwind of activity, one that’s repeated 38 weekends a year.

Photos by: TRIPP MICKLE / STAFF

|

Commercial airlines would be similarly priced for nonrefundable tickets, and people would have to arrive an hour and a half early to go through security.

“We’re saving time,” said Jennifer Stimberis, who manages all of Stewart-Haas’ travel planning. “You don’t have to pay to park. Say they get a flat tire, we’ll wait for them. A commercial airline would just say you’re SOL.”

The plane is full by 7:30 a.m. Most of the people on the flight are on the car crew. They spend the short, one-hour flight sleeping or playing games on their phones.

As the plane descends, SHR’s top communications executive, Mike Arning, explains that he used to live in Atlanta and fly commercially to races. He spent four hours on days he departed driving to the airport and going through security. He estimates he eliminated nearly 60 travel days annually when he relocated to Charlotte and started flying on the team plane. That’s time he gets to spend with his wife and two young sons.

“Finding a work/life balance in this sport is hard,” Arning says. “When you get good people, you want to hold onto them because they know what they’re doing, they know the sport, they know the team, so it’s important to be efficient with their time.”

After the plane lands, the team grabs luggage and rolls toward a white tent on the edge of the private landing strip at Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport. Avis has delivered more than 20 cars to the airport for SHR. Drivers get SUVs, crew chiefs get full-size cars and the 11-member crews get minivans to share. There are dozens of other cars for other NASCAR teams coming in that weekend. Avis does so much NASCAR business that it has a “race desk” with staff dedicated to working with the industry.

The crew members shuffle through a mountain of Ziploc bags with rental car keys and information looking for their name. Once they find it, they pile into minivans and head to the track. The garage opens at noon, and they arrive in time to unload the car off the hauler, wheel it to their garage stall and put it on jack stands for NASCAR officials to inspect.

The inspection takes approximately two hours. Around 4:30 p.m., the crew leaves for their hotel in nearby Carrollton, Ky. SHR has 44 rooms at the Hampton Inn. Crew members double up in 21 of those rooms, allowing the team to save nearly $13,000 in hotel costs a weekend.

The team has reserved the rooms through Sunday, just in case there’s a rain delay.

“Getting that many rooms the night of a race if there’s rain or the track comes apart would be next to impossible,” Stimberis says.

DAY TWO

Around 9:30 a.m. on Friday, Rick Hodges, the 58-year-old truck driver for Stewart-Haas’ No. 4 car, wheels a red cart carrying four Sunoco fuel canisters to a gasoline storage tank on the backside of the garage. He gets all four cans filled — gas is one of the few things teams get for free — and wheels the cart back toward the team’s hauler.

There are two things consistent behind the scenes for all NASCAR teams. First, everyone pitches in somewhere. Truck drivers like Hodges don’t just haul the race cars to the track; they also fill up gas canisters and take tools to pit road. The car crew members don’t just set the car up for the race; some of them also go over the wall and serve as members of the pit crew.

Second, everyone has a nickname. SHR alone has guys who go by Two Beers, Cheddar, Jabo, Tiny and Goldberg.

Hodges, who’s known as Otis, walks over to the garage to check on the crew. The garage, which opened at 8 that morning, is filled with the sound of buzzing tools and banging metal.

The day before a race is spent tuning the car. The shop began working on the team’s four primary cars more than a month earlier. Adding man-hours in the shop to the costs of items such as the Hendrick-made engine and fuel cells can boost the cost of each car to as much as $250,000.

Each of the four teams brings a primary car and a backup car to a race, which have a total cost of $310,000. The No. 4 car slated to race at Kentucky is the same car the team used in the Sprint All-Star Race in Charlotte. Cars are typically stripped two days after a race so that a new body can be hung on it. It is rebuilt and ready two weeks before Kentucky.

|

|

Photos by: TRIPP MICKLE / STAFF

|

The morning and early afternoon on the day prior to the race are spent with SHR’s four drivers — Stewart, Kevin Harvick, Danica Patrick and Kurt Busch — turning laps on the track. Every 10 minutes they return to the garage and the 11-man crews scramble to adjust the car. They are looking for the right balance between what they know will make the car go fast with what the driver feels most comfortable driving.

Practice ends at 4:30 p.m. and the teams push the cars out of the garage for inspection. Each team pays $4,730 to enter its car in the race, and that cost covers inspection. If they wreck a car in practice or qualifying, they will have to pay another $4,730 to enter their backup car.

The inspection process takes more than an hour, and while the crews push their cars through three inspection stations, many crew members grab food prepared by SHR’s personal chef (see related story).

“We’ve been going nonstop,” says No. 10 car crew chief Kevin “Two Beers” Pennell, as he leans against the car and shovels a spoonful of jambalaya into his mouth. “No time to eat.”

At 5:30 p.m., Gober, the truck driver for the No. 14 car, rolls a handtruck out of the garage and heads for an ice delivery truck near the infield entrance.

“Ten [bags] for the 14,” Gober says.

An employee with the ice company hands him a receipt for $100 total, $10 per bag, and Gober loads the bags of ice onto the handtruck. He wheels it to pit road for qualifying.

NASCAR adopted a new, elimination-style qualifying format this year. All the teams qualify simultaneously and the field is cut from 40-plus cars to 24 cars to 12 cars before setting the starting order for the race. The change has meant teams are buying more bags of ice each race weekend than they bought last year because they need to use it to cool down car engines between qualifying runs. SHR will spend $225 for each team on ice alone — or nearly $1,000 total for the race weekend.

As Gober dumps two bags of ice into a cooling machine pumping cold water through Stewart’s No. 14 car, he shakes his head and smiles.

“Twenty dollars,” he says. “I need to get in the frozen water business at a racetrack.”

DAY THREE

The crew for the No. 14 team is the first to enter the garage on race day, and they have special permission to be there.

After qualifying the previous night, the team was draining grease from the transmission and spotted small pieces of metal in the grease. They thought the transmission might be ruined, but they weren’t positive, so they arranged to have the team’s transmission specialist fly up that morning with the pit crews on the Stewart-Haas plane. He took one look at the transmission and said it needed to be replaced. A needle bearing had come out and chipped the gears. A new transmission costs $9,000, and installing it means the No. 14 car has to go from its qualifying position of 13th to the back of the field to start the race.

Stewart tries to take it in stride.

“The only place I can go is forward now,” he tells guests of sponsor Rush Truck Centers that afternoon (see related story).

Around 3:30 p.m., the sky darkens to the south of Kentucky Speedway. A band of pop-up thunderstorms is moving through the Ohio River Valley. It hits the track hard, dumping nearly a quarter inch of rain in the span of an hour.

Stimberis, a former SHR marketing executive who traveled to the race to assist with a sponsor hospitality program, immediately begins monitoring the rest of the day’s forecast. The race was rained out in 2013, and she knows that if it’s postponed this year, she will have to find hotel rooms for 30 pit-crew members who flew to Kentucky that morning and are supposed to fly home that night. She calls a contact at the speedway that afternoon to ask what local forecasters expect to happen. The rain is expected to clear out by 6 p.m., and if it doesn’t, then she will look to book rooms, an unexpected expense that could add another $10,000 to SHR’s weekend tab.

“If I can’t find rooms, they will just have to fly back,” Stimberis says.

|

| Photos by: TRIPP MICKLE / STAFF |

The teams seek cover from the rainstorm in the garage where they continue getting the cars ready. By the time inspection begins at 5:30 p.m., the rain has cleared and the steady growl of NASCAR’s Air Titan track-drying truck can be heard as it circles the speedway.

The pit crew and car crew for each team huddle behind their pit boxes along pit road during driver introductions. The pit boxes are about the only thing that NASCAR teams don’t transport to the race themselves. They pay a company called Champion Tire & Wheel to do that. It costs SHR $4,540 per team, or $18,000 total, each week.

Because of the rain that afternoon, which washed away the rubber put down during the previous day’s practice, NASCAR and tire sponsor Goodyear plan to flag a “competition caution” 30 laps into the race. They want to check the tires and see how they are wearing on what amounts to a “clean” track surface.

When the caution arrives, SHR driver Kevin Harvick pulls the No. 4 car into the first stall on pit road. The pit crew goes over the wall, pops off and replaces the right-side tires on the car in 5.4 seconds.

Each team goes through 15 sets of tires in a weekend. The tires cost $480 each, and SHR’s total tire bill for the weekend tops $129,000. Other than the race cars, it’s the team’s biggest weekly competition expense at the track.

Harvick pits again on the 78th lap and takes four tires. Crew chief Rodney Childers looks on from the pit box as the pit crew struggles through an 18.9-second stop. That’s six seconds slower than race leader Joey Logano.

The car crew chief, Robert “Cheddar” Smith, who doubles as the team gasman, climbs into the pit box, red with frustration.

“It don’t ever quit,” Smith shouts at Childers, as the cars roar past.

The pit stop costs Harvick 13 positions on the track and takes SHR’s best car out of contention for a victory at Kentucky.

About a quarter of the way through the race, the long-haul truckers for each team begin picking up the garage and getting the teams’ toolboxes in order. They collect tents from pit road halfway through the race, and with 40 laps to go, they wheel the drink coolers from pit road to the truck.

When the race enters the final 10 laps, Gober, who drives the No. 14 truck, latches the team’s toolbox and cooler down in the hauler. Moments later, when the race ends, SHR’s four drivers wheel their cars into the garage area and park them behind their respective haulers.

The car crew immediately scurries around each vehicle. They jack the car up, remove each wheel and replace it with “travel wheels,” which are used to transport the car. As the tire man returns the race tires to Goodyear, the rest of the team pushes the cars into the back of the hauler.

Each truck driver wheels the Sunoco gas cans in last. Gober looks out at the crew after he gets the gas cans into the truck.

“I’m good,” he says and flashes the thumbs-up. The crew flashes thumbs-up back and pivots to race toward their rental vans, which they strategically parked outside the speedway and close to an exit road.

They call this the “race after the race,” and each crew piles into their vans and rushes toward the airport. The sooner they get to the plane, the sooner they get home.

They arrive at the plane less than two hours after the race ends. Boxes of chicken fingers and mashed potatoes from Greyhound Catering are waiting for them on the plane. It’s been eight hours or more since their last meal, and they eat in silence while they wait for the plane to fill up.

Around 12:30 a.m., Stimberis steps into the plane door.

“Is everyone on board?” she asks, scanning the 25 rows of seats to be sure they’re full. “So I don’t have to stand outside anymore? Great. Let’s go.”

The plane takes off at 12:45 a.m. and lands an hour later at Concord Regional Airport. Most of the guys sleep on the way there. No one talks as they file out of the plane and collect their bags. They just hurry toward their cars and home.

In four days, they will do this all over again.