In the course of U.S. history, 40 years is not a long time. In the course of cable and sports history, however, it’s more than a lifetime.

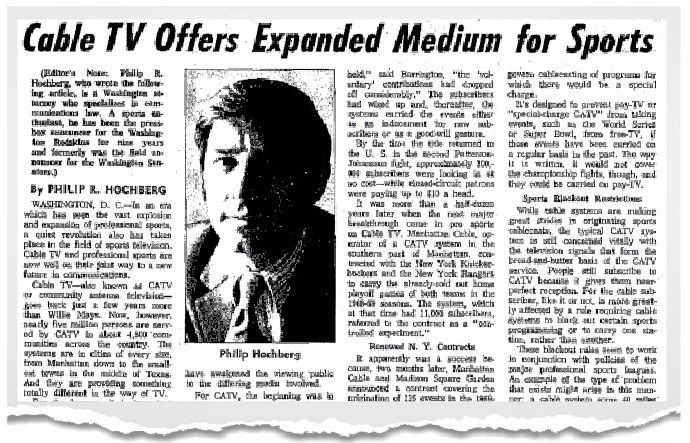

To put it in a certain perspective, members of SportsBusiness Journal’s 2011 Forty Under 40 class were still in diapers or not even born when I wrote the first article to appear in a national publication on cable and sports (“Cable TV Offers Expanded Medium for Sports,” July 3, 1971, The Sporting News).

Forty years ago, Bud Selig had just purchased the bankrupt Seattle Pilots and moved them to Milwaukee, where he was in the family’s auto business; David Stern was outside counsel to the NBA and practicing in New York; Gary Bettman was a Cornell undergraduate; and Roger Goodell was 12 years old.

It’s almost amusing likewise to take a look at where sports and cable were in 1971. Cable — or CATV (for Community Antenna Television) — was already a well-established business in the U.S. with some 5 million subscribers, but almost all of them were in small towns. The fifth-largest system in the U.S., for example, was located in Elmira, N.Y. (Currently in New York City alone, there are more than 2 million

subscribers.) Cable had been created some 23 years prior in the valleys in Pennsylvania and Oregon but was designed just to sell television sets by offering nearby stations to communities where television reception was spotty. Sports on cable was usually just the local high school game.

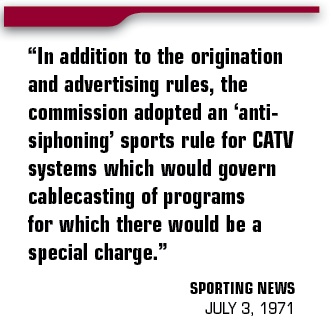

But cable was beginning to find its footing. In 1968-69, a system serving lower Manhattan had signed a contract to offer all of the sold-out games of the Knicks and Rangers to its 11,000 subscribers. By 1970-71, both Manhattan systems had a 125-event package from Madison Square Garden. By 1972, Home Box Office had entered the sports business, distributing games from the Garden by microwave to a dozen cable systems in eastern Pennsylvania. There was the hope of using satellites to distribute programming.

The universe changed on Oct. 1, 1975, when HBO offered the Ali-Frazier “Thrilla in Manila” to its subscribers. Suddenly, distance was no object — although money still was — since sports events could be transmitted from anywhere to anywhere. Later in the ’70s, two individuals with separate game plans, Ted Turner and Bill Rasmussen, discovered satellites and sports.

Turner was operating a failing independent station in Atlanta: WTCG, later WTBS, and later still the TBS Network. Needing programming, he purchased the Atlanta Braves in 1976 and used their games as a staple of his station’s lineup, creating the first “superstation.” At about the same time, Rasmussen, an enterprising former publicity man for the New England Whalers of the World Hockey Association, had the idea that if he could lease satellite time, he could show University of Connecticut games to all 12 Connecticut cable systems. He got it and suddenly found that his Entertainment and Sports Programming Network (now ESPN, of course) could deliver sports events to any cable system in the entire country that had a receiving dish. ESPN signed on on Sept. 7, 1979. Now things had really changed.

Sports interests fought the basic idea behind cable’s bringing in non-local television signals, such as WTBS. They were concerned that non-local games would hurt attendance and the sale of their own local broadcast rights. Only when their own local systems entered the marketplace and bought the rights from the home team did the teams and leagues begin creating business plans to adjust to this new world. By the end of the 1980s, more than 50 million homes were cable subscribers, a tenfold increase in less than 20 years.

By this time as well, regional sports networks, such as Madison Square Garden Network, had begun carrying the games of the local MLB, NBA and NHL teams, as well as college teams, to cable subscribers. Eventually, some 32 RSNs — 20 of them affiliated with Fox, nine more affiliated with Comcast/NBC — had been developed carrying virtually every professional team. And, earlier this year, the University of Texas announced the Longhorn Network, the first network dedicated to a single collegiate program.

The lone holdout in the marriage of the cable and sports worlds had been the NFL. The league had been more than successful in its dealings with the major broadcast networks for its Sunday games and “Monday Night Football.” Although ESPN had had contracts with the NCAA, NBA, and the United States Football League, it really didn’t achieve its full-fledged status until its 1987 NFL contract. Indeed, it may have been a two-way street, since former NFL Commissioner Paul Tagliabue was quoted as crediting ESPN with “revolutionizing” the league by taking “the draft, the pregame and highlight shows, and other NFL programming to a new level.”

In 1994, a few years after the ESPN-NFL deal, a significant cable competitor showed up: direct-to-home, small-dish satellite services. While both DirecTV and Dish Network began service, the former jump-started its service by partnering with the NFL on Sunday Ticket which, for the first time, allowed subscribers to view their choice of any out-of-market game.

By the turn of the century, the cable sports industry had gone from mom-and-pop operations to the behemoth of ESPN on a national level. And within 10 years, ESPN and ESPN2 had grown to more than 100 million subscribers each.

Where do cable and sports go from here? In the blink of an eye, they’re going online, to your computer, smartphone and tablet. Who knows, maybe with voice recognition and maybe with personalization, you might be able to pick your own camera angles. And many events are available in 3-D.

Has the world changed in the last 40 years? Well, a little bit. In addition to the four national over-the-air networks that carry sports, one typical major-market cable system dedicates 87 channels to sports programming, including pay-per-view, high definition and 3-D. (And that doesn’t include wireless services, such as phones, laptops and tablets.)

To say, as I did 40 years ago, that cable and sports had a great potential seems a bit of an understatement.

Philip R. Hochberg (PHochberg@srgpe.com) is a Washington lawyer who represents professional and collegiate sports interests.