He held the small, torn scrap of paper at a distance, tilting it to catch the light from an overcast winter afternoon.

Marvin Miller came upon the note a month earlier, while arranging boxes in a hall closet. A sheet torn from a notebook floated down, landing on his foot. On it, he found a brief list. From first glance, he recognized his wife’s handwriting.

|

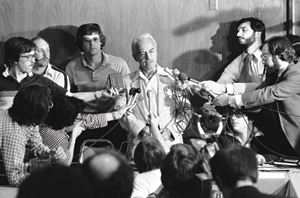

PATRICK E. MCCARTHY

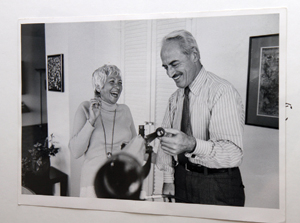

Miller, in his New York City apartment, inspired loyalty in the MLB Players Association membership but anger in many fans. |

How could he not.

Marvin Miller met Terry Morganstern in 1936, when she was a student at Brooklyn College. They were two months shy of their 70th wedding anniversary when she died in October 2009.

“Her handwriting was so distinct,” said Miller, running fingers across the small sheet of paper.

He turned to look over his left shoulder, out the vast spread of windows of a 32nd-floor Manhattan apartment that has been his home for 35 years. When the Millers moved here, they were taken by the unobstructed views of the Empire State Building and the East River. Development has stolen his clear look at the river, but the wider vista remains breathtaking.

“I’m not superstitious,” Miller said, eyes dropping back down to the note from his wife. “I can’t be sure when she wrote it, or why.

“Maybe it was for me, as a reminder.”

As he explained the significance of each line, Miller cast the words as advice she left behind. But they could just as easily be applied as lessons from an extraordinary life.

Play the point.

Don’t suffer twice for the same problem.

The end game is very important.

“My wife was a remarkable woman,” Miller said. “She really knew everything that was going on.”

PLAY THE POINT

He did not raise his voice at a bargaining table, no matter how tense the discussion turned. When leading a meeting of players, he chose to teach rather than preach.

Throughout his 16 years as executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association, Miller was determined to contain his emotions; to make sure they didn’t get in the way. He knew that they could. He learned it, of all places, on the tennis court, after flubbing several shots during a lesson.

“Your strokes are coming along fine,” the pro told him. “But I have to tell you one thing. If you mess up a shot when you should not have, you lose your concentration. And then you mess up the majority of the next five or six shots. Don’t do that. Play the point. You hit a bad shot, put it behind you. It’s gone. Play the point.”

Years later, while teaching his wife to play tennis, Miller shared that advice. She embraced it and, when necessary, reminded him to do the same — and not just on the tennis court.

Packed tightly into 10 cardboard boxes stored in the main library at NYU, thousands of pages documenting Miller’s labor career are filed alphabetically by subject. Agent meetings. Arbitration cases. Benefit plan. Blue, Vida. Collusion. Commissioners. And on and on, a roll call of issues that occupied Miller’s time from his hiring by the MLBPA in 1966 through 2002, when he donated the papers, 20 years after his nominal retirement.

There are contracts, budgets, minutes from meetings, speeches, notes, research reports and clippings from newspapers and magazines, all filed in 269 manila folders. Twenty-five are marked “Correspondence.” They are not what you would expect. Sprinkled in are thank-you notes from current and former players, such as Hank Greenberg, Johnny Mize and Frank Crosetti, who wrote separately after he bettered their pension in 1980. But, mostly, the files are stocked with letters from fans.

Many were angry.

Typical is a short note from Steve Longenecker, a 30-year-old high school social studies teacher from Quarryville,

|

ICON SMI; PATRICK E. MCCARTHY (2)

Miller threw himself into his work, but the love of his life was wife Terry, who died in 2009. |

Pa., who wrote to Miller on May 25, 1981, as baseball steamed toward a strike that would last nearly two months and cancel 713 games.

“Baseball has been very good to you,” Longenecker wrote in blocky print, “so cut the crap and play ball.”

As the face of the union through two decades of intermittent labor unrest, Miller received reams of similar notes, many of which suggested solutions. On a single day during the ’81 strike, he got proposals from a law firm representing the AFL-CIO, an economist at the University of Pennsylvania and a 14-year-old boy in Illinois, all of whom attached complex, detailed plans.

Miller not only responded to the letters when he had time, he took them home to discuss with his wife. He kept them; hundreds of them.

“They were a reminder,” Miller said after listening to passages from a few. “Not everybody is at the same level of understanding. Not everybody has the same views about anything. It was important to keep that in mind.”

That even held true within the union, especially at its outset. Miller was the association’s first executive director. He came with a traditional trade union pedigree. He had been an economist with the United Steelworkers for 16 years and assistant to the president of the union for the last six. He served on presidential commissions for John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson.

|

AP IMAGES

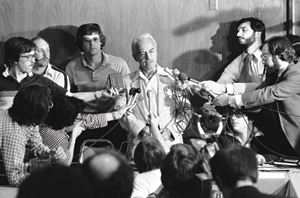

Don Fehr (left), with Miller and Richard Moss, says you could gauge Miller’s mood by the drink he ordered at lunch. |

Few among the players embraced him. Though created in 1953, the PA had operated in the shadow of MLB, funded by the commissioner’s office and headed by part-time advisers who were cozy with ownership. Late in 1965, worried that the owners would railroad a plan to reduce funding for their pensions, the players formed a committee to select a full-time executive director who would manage the union from an office in New York. A friend of future Hall of Fame pitcher Robin Roberts recommended Miller.

Roberts wasn’t sure he could get him through a vote of the rank-and-file, though. Managers, coaches and general managers spoke of Miller as if he were a villain out of “The Untouchables.” Some warned players that he was a Communist. Even after the players voted to hire him, Miller found many were reluctant to embrace his advice.

“They worried about the wrong things,” Miller said. “Worried that the owners don’t like me. And the commissioner doesn’t like me. And the league presidents don’t like me. It came up again and again.”

After three or four meetings with the player representatives, Miller confronted them.

“It’s important to understand that labor-management relations is not a ballgame,” Miller told them. “It’s an adversarial exercise where, with rare exception, what is good for you is bad for the owners. And what is good for the owners is bad for you. There are exceptions, but not many. It’s not in the nature of things for them to be pleased with me.

“You have to understand, we are adversaries. If at any point the owners start singing my praises, there’s only one thing for you to do, and that’s fire me. And I’m not kidding.”

It was a turning point for the young organization, and for the culture of professional sports. It led to the first collective-bargaining agreement, to free agency, to arbitration, to improved pensions and benefits. It changed the way baseball players saw themselves, and their place. As baseball changed, all of sports would change.

Leading though listening: ‘Marvin would never move until every single guy had their say’It happened each spring, at every major league camp.

Marvin Miller gathered the players in uniform, typically in the outfield, for a 90-minute union meeting guaranteed by virtue of a clause he negotiated in the first collective-bargaining agreement. There, he mixed a rundown of the current labor issues with a primer, or reminder, of the core principles of the players association. Chief among them: that they were far stronger collectively than individually, and that they would achieve their goals only if the owners knew they were willing to stand and fight.

|

AP IMAGES

Miller was the public face of the union, but behind closed doors he helped foster the MLBPA's culture. |

As he spoke, Miller slowly and steadily lowered his voice, forcing players to gather more tightly to hear him. “He talked to you man to man,” said Steve Rogers, a five-time all-star pitcher who was active as a player representative and now serves as a special assistant to union head Michael Weiner. “He didn’t come in and beat you over the head with a stick. He was measured in his delivery. He was authoritative without being an authoritarian. It was an education process from the very first spring training meeting I was involved in.

“He was bigger than life.”

It was there, during those meetings, that Miller bred and then fostered the culture of the most powerful union in sports.

Critics often painted him as a puppeteer, an ideologue who turned negotiations into an ego-driven battle of wills — his vs. the owners’ — rather than a process meant to better the players’ lot. But players who dealt closely with him insist that was not the case.

Among the more telling stories is that of Ted Simmons, the all-star catcher who nearly became the test case that led to free agency. Like several players, including pitchers Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally, Simmons was playing through the 1975 season without a contract. Miller had advised them that if they went through the season without signing, they could file a grievance challenging the reserve rule that bound players to a team in perpetuity. If they won, they would be granted free agency and assure it for others in the future.

Simmons was at loggerheads with the St. Louis Cardinals, who had offered him a $25,000 salary for the year. He wanted $30,000. His mother-in-law was recently divorced. Simmons said he wanted the extra $5,000 to help her make her house payments. When the Cardinals wouldn’t come off their offer, Simmons asked Miller’s advice.

“He said, ‘I can’t decide that for you, Teddy,’” Simmons said. “He said the environment was a difficult one. It would be a tough row to hoe. I had family to worry about. I know they wanted someone to test it, but Marvin wasn’t going to do anything to push me. He told me to do what was best for us.”

At the All-Star Game, Cardinals general manager Bing Devine invited Simmons up to his hotel room and staggered him with the offer of a two-year contract with salaries of $40,000 and $45,000. Simmons signed. Messersmith and McNally ended up as the named players in the grievance, which the union won.

“I heard for 20 or 30 years that Marvin told us all what to do and we just followed along,” Simmons said. “Man, that’s not even close to what happened.

“His role as the director was to convey the information and present a perspective, but he would never commit to that perspective until everyone had their say. I remember sitting there so many times, and you’d hear players say the most insane, incomprehensible things — hour after hour, day after day. And Marvin would never move until every single guy had their say, no matter how absurd. Marvin would never step in. He’d sit there quiet as a church mouse and let us get to the place that he knew we were going to go.”

The MLB Players Association’s spring training meetings continue today, though they have moved from the outfield to the clubhouses, which are far larger than they were when Miller was making the rounds.

“What the players did under Marvin’s leadership is the foundation of everything there is today,” said Weiner, who became MLBPA executive director in 2009. “The message that has been communicated to players ever since I started here, by the staff and by player leadership, is the connection between generations of players. The players today understand they have the rights of today because players before them sacrificed, fought and stood their ground to get that. They understand that Marvin was the start of all that.

“Everybody understands that legacy.”

— Bill King

“Here was this little guy with a soft-spoken voice, but he was such a commanding presence,” said Bob Locker, a relief pitcher who served as a player rep twice while playing from 1965-75. “Marvin Miller is a giant. The impact he’s had on all of professional sports — not just baseball, all sports — is amazing.”

When the players hired Miller in 1966, the minimum annual salary was $6,000 a year and the average was $19,000. They had no power and little voice. When he retired at the end of 1982, the players’ economic lot had turned mightily and the union was the most powerful in sports.

“This man changed my whole life,” said Ted Simmons, the former catcher who went from making $12,000 as a rookie in 1970 to $1 million as a free agent in 1983. “When someone says to you, ‘Who do you have to thank?’ — It’s always about the guys who taught you to hit the slider or block the ball in the dirt. And those people are really important, but no one is close to Marvin.

“Others have been great conservators. But the trailblazer? Nobody is even close.”

DON'T SUFFER TWICE FOR THE SAME PROBLEM

One of the perks of life in the early days of the players association was its location on Park Avenue in the Seagram Building, long home to two of New York’s famed power lunch spots, the Four Seasons and Brasserie. Miller, general counsel Don Fehr and three staff members shared 2 1/2 offices and a conference room on the top floor. Three or four days a week, Fehr and Miller lunched together downstairs.

Miller always ordered a cocktail with lunch. Fehr soon learned that he could gauge his boss’s mood by his drink. If he called for a screwdriver, things were going swimmingly. If he had a martini, he was perplexed by something and intended to spend the hour giving the matter more thought. And if he ordered whiskey ...

“If he had whiskey,” Fehr said, chuckling, “well, there was something weighing on his mind.

“He’d come in and say, ‘Jack Daniel’s.’ And I’d say, “What’s wrong?’”

Miller fretted far more often than his drink choice would indicate. He was a worrier by nature, though Fehr and others say they never saw it. Terry knew. She saw it in his brow when he came home after preparing for a board meeting with player reps, or after a long night of negotiation that felt more like a head-first dive into a brick wall. “Don’t suffer twice for the same problem,” she’d tell him. But it was his nature to worry, and to worry most about that which was most difficult to predict.

It was 1972, and Miller was in his sixth year at the players association. He had expected a quiet winter. The only portions of the CBA open for negotiation were pension and health care. The union asked for cost of living increases. That was it. The two sides negotiated intermittently up until spring training, when the players rejected a management proposal overwhelmingly, only to have the owners come back with an offer of even less. Miller took it as a warning shot, a sign that they intended to test the union’s resolve.

On his tour of spring camps, he asked players to vote on whether to authorize a strike if an agreement wasn’t in place by the end of March. All 24 clubs voted yes, most of them unanimously, delivering a tally of 663-10. Still, the difference between authorizing a strike and striking is like the gap between riding an escalator and jumping out of a plane.

A day before the strike deadline, Cardinals owner Gussie Busch dared the players to try their luck.

“We’re not giving them another … cent,” Busch said. “If they want to strike, let them strike.”

While Miller had secured the authorization to strike, he wasn’t sure it was worth it. The sticking point, pensions, wouldn’t affect the players for years. This didn’t feel like the ground on which they should plant their first flag. Miller made one final proposal: that the two sides submit the dispute for binding arbitration by the White House.

The owners refused. They felt they had given enough. In the five years since the players hired Miller, the minimum salary had increased from $6,000 to $13,500. The average had doubled from $17,000 to $34,000. Benefits and pensions also had escalated rapidly after two decades of stagnation.

On a flight from Scottsdale, Ariz., to Dallas for a meeting with union leadership, Miller sat in front of the Oakland A’s player rep, pitcher Chuck Dobson, and his alternate, Reggie Jackson. He listened as both spoke exuberantly of their resolve.

“They were all gung-ho,” Miller said. “But, you know, I’ve seen gung-ho before. It doesn’t register with me until I realize I’m dealing with people who know exactly what they’re in for.”

At the meeting in Dallas, Miller laid it all out. He told the players they should report for the season while he continued negotiating; that the issue wasn’t worth striking over; that they could always walk out later if the owners wouldn’t move. He was stunned by their response.

“They talked me down,” Miller said. “I never saw such rebellious people in my life. Everybody wanted the floor.”

Miller suggested the players pass a rule that no rep speak twice until they’d all had a chance to be heard. They did it. And then they lined up, one after the next, to speak in impassioned, sometimes angry tones.

|

AP IMAGES

Miller calls ‘81 “the most principled strike” he was involved in. |

“They took me to task,” Miller said. “They said ‘We understand what you’re saying, but you’re not showing much confidence in us. We know who we’re dealing with. We know they’re never going to respect us unless we indicate we’re not going to take no for an answer on a perfectly reasonable set of propositions. You’ve taught us you don’t crawl, you don’t get to your knees. This is an attempt to get rid of us as a union — and we recognize it.’”

Miller listened, but he held fast. He pointed out that they had asked how long a strike might last, which he took as indication that they weren’t prepared for one. They should picture the longest stretch imaginable, and then add a day. He reminded them that if they voted to strike, they would leave the Dallas meeting and head home to scattered cities, some of them abroad. That was a dynamic that the steelworkers never had to worry about. He pointed out that they didn’t have a strike fund. At the very least, he told them, they should postpone long enough to build one.

They talked for hours. Players came and went from the room, canceling flights, some more than once. When they called for a vote, he stalled, hoping they would lose their steam. They didn’t. They voted 47-1 to strike.

It lasted 13 days, canceled 86 games, cost the owners a reported $5.2 million in gate receipts and the players $600,000 in salary, and ended in a fashion that would predict the outcome of disputes to come. The lost revenue fractured the owners, who settled under terms identical to those the players asked for at the beginning.

The players got their pension and health benefit increases at exactly the rates they demanded from the start.

THE END GAME IS VERY IMPORTANT

For most of his life, he thought about the end game as a stage in a negotiation, that final juncture at which his dogged preparation paid off. Now, at 93, he thinks about it differently. It is more about mortality. About choices. About changes — some of them welcome, but many not.

Miller points out proudly that he played singles tennis past his 91st birthday, but he hasn’t swung a racket in more than a year and concedes — well, almost concedes — that he probably won’t play again. In June, he caught his foot on loose carpet in the elevator and fell, fracturing bones in his spine. When doctors at the hospital told him that the only remedy was rest, he insisted they let him go home. He required a hospital bed and round-the-clock care. After a couple of months, he shed the day nurse. Then the night nurse. Then he got rid of the hospital bed.

“And then,” Miller smiled, “I hung up my cane.”

He and his wife often spoke of how they hoped to handle this late stage of life.

“She long discussed with me people we know who lived exemplary lives but kind of messed things up in the latter part,” Miller said. “It wasn’t like them at all. But they did these things, and now, well …”

He shook his head slowly and his voice trailed off.

He said he is more careful about his affairs now, and particularly about his public life. He still does interviews, but he is not as free with his thoughts. While he can debate a point fiercely and sparks when challenged, he worries that he might be off on a detail. He is less likely to go off with both barrels, even when it involves adversaries who were targets for years.

When he wrote his memoir 20 years ago, he flamed the usual suspects — former Commissioner Bowie Kuhn and the owners and executives that he found to be short-sighted — but he also took players such as Carlton Fisk and Catfish Hunter to task for forgetting what the union had done for them. To some, it came off as petty. Miller didn’t much care.

Retelling stories from the book years later, he tries not to mention the names of some who might be cast unfavorably.

He hasn’t gone soft, mind you. Just careful.

Because the end game is very important.

The gains of a decade can be lost in a day.

|

PATRICK E. MCCARTHY

At 93, Miller still gives interviews but is less likely to tee off on old adversaries. |

Late in the 1970s, the owners began pressing hard to increase compensation to clubs that lost players to free agency. Miller saw it as an assault on the most valuable right the players had acquired, the ability to put their services out to bid. In 1976, the year before the first free agent class hit the market, the average salary was $52,300. Four years later, it had nearly tripled to $143,756.

Rather than arguing to dampen salaries, the owners focused on the threat free agency posed to competitive balance. They wanted a team that lost a free agent to be able to replace him with a player from the major league roster of the club that signed him. Though the owners called it a minor tweaking of the agreement, Miller warned the players that it would wreck the market for all but the upper tier. Clubs wouldn’t sign a midtier free agent if they faced losing a similar, but lower-paid, player of their own.

As early as 1979, he was preparing players for the fight. In what was either a rough draft of a presentation to players or a note to himself while crafting strategy — 30 years later, he isn’t sure which — Miller wrote passionately and presciently.

“The frontal attack I anticipate from the owners will be in the area of reserve rules,” he wrote. “We cannot put players into a position of being ransomed. … Free agency will become meaningless.”

The talks that led up to the ’81 strike were not so much negotiations as stare-downs. The owners demanded. The players refused. The owners implemented new rules. The players went on strike.

From the beginning, Miller warned that the owners’ goal was to break them; that they should brace for a long and ugly fight. It would last 50 days, cancel 713 games, and cost the owners $72 million in revenue and the players $28 million in salaries. As they had in previous tests, the players proved solid in their resolve.

“Marvin had prepared the players over the years, reminding us over and over that in order to get what you want, you’ve got to be willing to stand up and fight,” said Doug DeCinces, the Baltimore Orioles third baseman who was the AL player rep in 1981. “He was always prepared, and he prepared the players. We knew what to expect and what we had to do.”

That year stressed the union as never before.

A lengthy in-season strike not only took money from the players’ pockets, it also scattered them. Eight players who served on the negotiating committee, including DeCinces and NL rep Bob Boone, joined Fehr and Miller in talks with the owners’ negotiators. Some of the talks were held in Washington under the watch of a federal mediator. When the union reps weren’t bargaining, they were on the phone with player reps from the teams, trying to keep them informed. But, mostly, they used press conferences as their conduit.

When the mediator imposed a gag order, Miller was reminded of how badly he needed access to the press. “It’s not like we had Facebook,” DeCinces said. Within days, several players — notably Dodgers second baseman Davey Lopes and Tigers pitcher Dan Schatzeder — told reporters that they were frustrated by what they saw as a stall in the negotiations. Perceiving a crack in the union, management walked out of the talks.

DeCinces and Boone told Miller they wanted to meet with the rank-and-file. Miller worried that open sessions like that would only fracture them further, but when they insisted, he acquiesced. They met with about 100 players in Chicago. There, players voiced worries about lost paychecks, but none of the them said they were willing to give in. The real test would come in Los Angeles, where about 300 players showed up, including Lopes.

Boone, DeCinces and Miller explained their position, then invited players to weigh in. Many spoke, but to this day, DeCinces remembers most clearly the words of Dodgers outfielder Reggie Smith, who took Lopes to task for undermining Miller and the players on the negotiating committee. “This isn’t [the committee’s] strike,” Smith shouted. “It’s our strike.”

“The whole time, Marvin was sitting back, listening,” DeCinces said. “He wasn’t banging on the podium asking for support. Far from it. He turned the room over to the players, and from there it was a steamroll of support for the association’s position and a whole lot of anger for anybody who would threaten that solidarity.

“When we came out of that meeting, Marvin had a spring in his step.”

A day later in New York, with the players united and the owners’ strike insurance a week shy of expiration, the two sides began a marathon session that concluded at 5:30 the following morning, with a settlement that allowed for compensation, but in the format on which the players had insisted.

Thirty years later, Fehr uses Miller’s approach in those meetings of ’81 — facilitating discussions among players rather than directing them; asking questions before ever offering advice; recusing himself from bargaining when owners claimed he was the barrier — as an example of what he sees as a distinguishing factor that enabled Miller to raise the most potent union in sports.

“The tendency would be to look at this and make it personal to him — he did something,” said Fehr, who succeeded Miller as executive director in 1983 and served through 2009. “And he did. But what he did was to get the players to do things for themselves, and that’s a different thing.”

|

PATRICK E. MCCARTHY

Fehr found it reassuring that Miller “was never obviously rattled or excited by anything.” |

Miller still calls the ’81 walkout “the most principled strike” he was involved in. The owners tried to get the union to accept direct compensation by carving out exemptions for large groups of players. It wouldn’t apply to those who had been free agents before or to those with more than 10 years of service. With each offer, the owners increased the number that would be exempt.

“They wanted them to sell out the future players,” Miller said. “There they were, 40 days and 45 days in, taking the losses, taking the beatings, when almost every one of them would be exempt. And they still wouldn’t fold. That’s what I call integrity.”

On the morning they settled, Fehr felt an understandable burst of adrenaline. The union had won on all the points that were important to the players. Management tested them, convinced that they’d crumble after a few lost paychecks. Instead, it was the owners who buckled, coming apart as soon as their strike insurance ran out.

“Well, we got it done,” Miller told Fehr after they struck the deal. “It took longer than I would have liked, but the players were great. You did what you had to do. Everybody was great.”

He asked Fehr if he would sit in for him as a guest on ABC’s “Nightline.” “I’m too tired,” Miller said.

And that was it.

“I would have thought that after that meeting, there would have been, even if only in private to me, some sort of obvious display of satisfaction, of accomplishment,” Fehr said. “Nope. Marvin always had a flat display of personality. I don’t think his emotions were flat, but they were always displayed to be flat. He was never obviously rattled or excited by anything. That, to me, was reassuring. And I’m pretty sure it was really reassuring to the players.”

The import of that night, which would frame negotiations in baseball for years, was such that Fehr remembers minute details, including Miller’s parting words:

“Gonna go home and see Terry.”