getty images

Leaning over a small yellow notepad, New Jersey’s chief gambling regulator wrote the word “Bill” on the first page, then circled it. Around the circle, he sketched a dozen small, inward-pointing arrows, until it was enveloped.

“Once you initiate the legislative process, you have all the lobbyists and all the stakeholders focused on: How does this impact me,” said Dave Rebuck, director of New Jersey’s gaming enforcement division since 2011. “They’re all looking for a benefit that works for them without having a detriment that hurts their existing business model.

“You may have the best bill written on day one. But after all this input, six months later that could be significantly different.”

This is the nature of the political process, which in many ways will dictate both the pace and direction of the much-anticipated rollout of legal, regulated sports betting in the U.S. in the coming years.

Bettors have wagered more than $2 billion at New Jersey sportsbooks since William Hill took its first sports bet at Monmouth Park racetrack on June 14, a month after the Supreme Court struck down a federal restriction in place since 1992. Through February, New Jersey sportsbooks had generated $125 million in revenue from sports betting and paid about $15 million in state taxes.

Lest you think this is entirely attributable to its larger population, New Jersey is running laps around other states on a per capita basis as well, bringing in $55 per over-21 adult in January, compared to $24 per adult in Rhode Island and $16 per adult in Delaware. Other states that have introduced sports betting in the last year all have performed even worse.

You might think that the boffo results in New Jersey would lead others to replicate its practices. But the bills proposed thus far this year in 23 states mirror the hodgepodge that has emerged in the eight that already are up and running.

New Jersey has the most liberal of the regulatory structures, allowing bettors to wager using their mobile devices, with a tax rate of 8.5 percent on bets placed in person and 13 percent on those placed online. West Virginia also allows mobile wagering, with a tax rate of 10 percent, regardless of how a bet is placed. Pennsylvania allows mobile betting but taxes sports betting at 36 percent and charges operators $10 million for a license. All three allow bettors to sign up and deposit money into accounts online, something they can’t do in Nevada.

Rhode Island did not allow mobile wagering when it welcomed sports betting last year but added it in response to disappointing revenue. Like Nevada, it will require in-person registration. It also collects a staggering 51 percent tax rate that it calls a “revenue share.” Delaware, the first state to take bets after the Supreme Court ruling, does not offer mobile wagering and holds on to 50 percent of the revenue from sports betting.

Mississippi does not allow traditional mobile wagering, but it will let its casinos develop mobile apps for use on their property, a quirky approach that both drives bettors to its resort casinos and allows sportsbooks to take increasingly popular in-play wagers, bets placed at odds that change throughout the course of a game. It taxes sports bets at 12 percent.

In New Mexico, two tribal casinos are the only locations taking legal sports bets.

Then there is the District of Columbia, which in its haste to beat neighboring states to market cobbled together an unprecedented sports betting framework that promises to tantalize many but satisfy few.

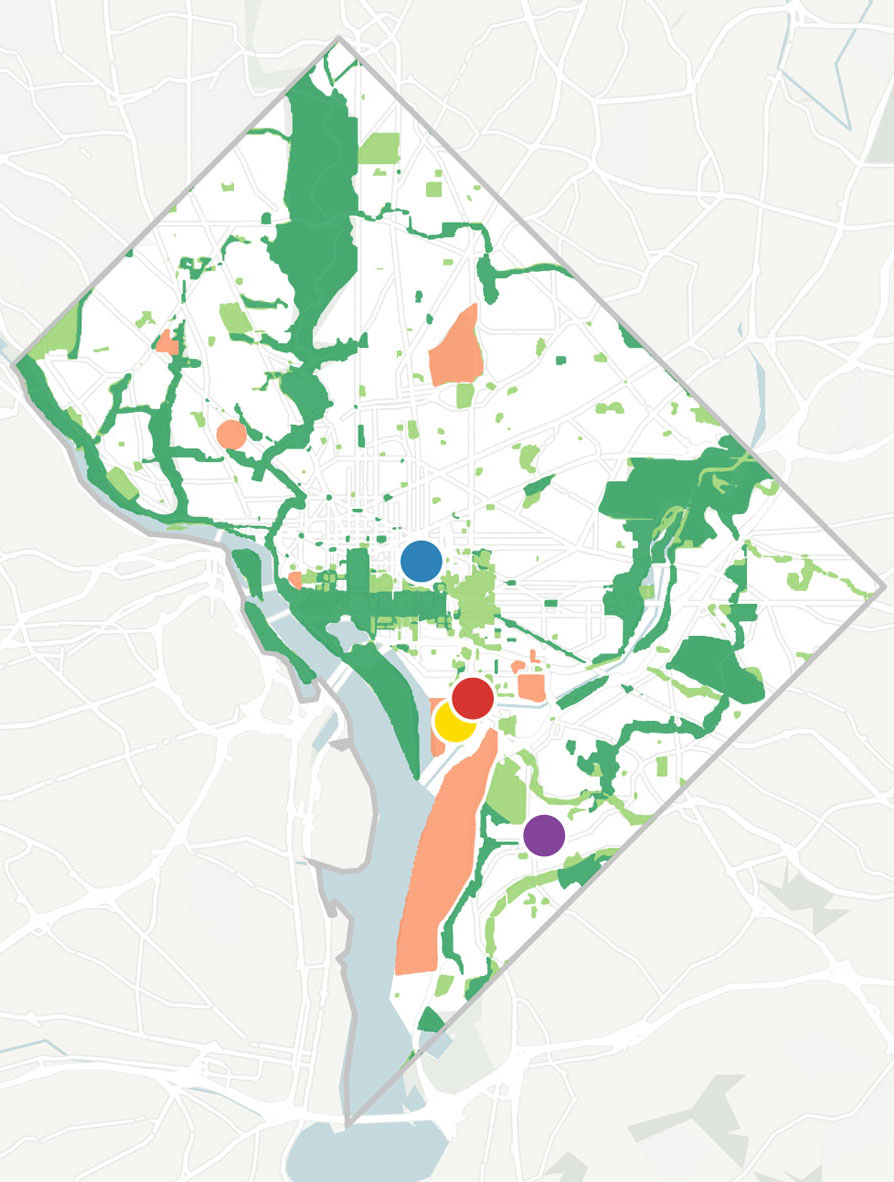

Sports betting in D.C.

Four sports facilities in Washington, D.C., will qualify for licenses to house sportsbooks with two-block carve-outs around the properties, while the DC Lottery holds rights to mobile sports betting elsewhere. Betting is prohibited on federal land.

⚫︎ National park

⚫︎ Military bases

⚫︎ Other federal land

⚫︎ Capital One Arena

⚫︎ Nationals Park

⚫︎ Audi Stadium

⚫︎ St. Elizabeths East Entertainment & Sports Arena

Each of the four arenas and stadiums in the district that house pro teams — Capital One Arena, Nationals Park, Audi Stadium and the St. Elizabeths East Entertainment and Sports Arena — will qualify for licenses to host sportsbooks, setting them up to be landlords to operators such as MGM, William Hill or Caesars. Bars and restaurants could apply for another class of license that would allow them to install betting kiosks.

The rub of that seemingly open access is that none of those operators or facilities would be able to take bets on mobile apps outside of their property. Those rights will be held exclusively by the DC Lottery, which intends to work with its current vendor on a sports betting product.

As if crossing a state line to place a bet wasn’t enough of a lift, D.C. will have apps blocked based on where you are in the district. Not only are there exclusive carve-outs within two blocks of each sports venue, but betting will be prohibited on federal land.

“The industry’s biggest concern with the D.C. model is that there is essentially a monopoly,” said Sara Slane, senior vice president of public affairs and the point person on sports betting for the D.C.-based American Gaming Association. “Secondarily, it’s going to be extraordinarily confusing.

“I happen to have firsthand knowledge of this. I live in Maryland and I work in D.C. What they’re talking about with these zones where you can access different apps and then your app is going to shut off as soon as you hit 9th Street and H — I don’t think it’s very consumer friendly.”

How the law emerged this way offers a window into the political nature of gaming legislation. Local team owners got access, though not the open mobile platforms that they and the sportsbook operators wanted. Small businesses got access, though it remains to be seen what the value of a kiosk in a sports bar will be in a world going mobile.

But, in the end, the lottery won the grand prize, a place in the pocket or purse of every mobile device-carrying sports fan in the district.

“The approach in a state is typically going to be largely dictated by the primary stakeholders in that state,” said Chris Grove, managing director of sports and emerging verticals for Eilers & Krejcik Gaming, a leading gaming research and advisory firm. “In some states that may be the lottery. In other states, commercial casinos. In others, tribal casinos. In others, racetracks. In states like Massachusetts, DraftKings. So each state is going to have a constellation of stakeholders with different things they’re trying to get out of regulated sports betting — or trying to make sure don’t happen as a result of regulated sports betting. Those agendas end up exerting a lot of influence over the final legislative product.

“These early states are not an aberration,” Grove said. “This is how it’s going to be. This is not a fluke in the first few states. We’re going to see a pretty fragmented approach across the states that eventually tackle sports betting.”

■ ■ ■ ■

About 15 minutes before the puck dropped on a recent New Jersey Devils game against the Washington Capitals, a few friends huddled at a high-top table in the William Hill lounge on the main concourse of Newark’s Prudential Center, where an “ambassador” from the sportsbook helped one sign up for an account.

Opening a sports betting account isn’t like most of the sign-ups that might occur in a sponsored area at an arena or stadium. State regulations typically require not only a name, address, phone number and email address, but also a social security number and date of birth, information consumers aren’t always eager to provide.

Then there’s the matter of funding the account — depositing the money that will be used to place the bets. New Jersey regulators allow for as lenient a sign-up process as any state, letting bettors to fund online using their credit cards, but analysts estimate that fewer than half of U.S. credit card issuers approve charges used for gambling. They say about 70 percent of those who try to sign up in New Jersey will have the first card that they try declined.

The William Hill Sports Lounge at the Prudential Center has "ambassadors" on hand to help visitors sign up for accounts and place bets.New Jersey Devils

Fortunately for the sportsbooks, there are ways to navigate that.

Since most consumers have at least two credit cards, they likely have one that will work. If they don’t, they can use a credit or debit card to load funds onto a William Hill prepaid card, which works like any prepaid Visa card. But a decline while signing up can be a jarring experience. Some won’t give it a second try.

This is why William Hill considers its lounge the most valuable component of its sponsorship with the Devils, which also includes a high-profile update of NHL game odds that appears on the massive center-hung board between periods and title sponsorship of Devils pregame and postgame shows on TV.

“Having fans walk into a place where we have people who will help you, regardless of the issue, is a good thing,” said Ken Fuchs, who joined William Hill U.S. as president of digital in December after stints as CEO of sports tech company Stats and as a global vice president at Yahoo. “When you look at trying to roll out something nationally, that education aspect is important. And that touchpoint is a good thing.

“This space provides an access point for sports fans to learn how to bet. To understand how you download the app. The mechanics of paying and registering. The types of information you have to disclose. Our people are trained to walk them through all that.”

William Hill is one of three sportsbooks that sponsor the Devils. Caesars Entertainment has its name on one of the arena’s premium clubs, using the sponsorship to promote its Atlantic City properties to Devils fans and concertgoers. FanDuel, which signed on to promote its daily fantasy product in 2018, extended that sponsorship to include sports betting this season. The Devils expect to add at least two more sponsors in the category.

When the Devils signed their first deals at the start of the season, team President Hugh Weber predicted that the category would be worth $5 million annually to the franchise, a bold statement that he says was intended to drive home the import of the new category. While he would not specifically confirm that the franchise hit that number this year, he said it was “pretty darn close.”

Weber pointed to the sportsbook-friendly regulations of New Jersey and the NHL as reasons the category has flourished for the franchise.

“On this one, the opinion of our [sportsbook] partners matters more than ours,” he said. “And they find this to be a much easier market to do business in. So maybe the structure in which it’s brought to market does matter, because they’re choosing to double down here.”

While the state’s gaming regulator, Rebuck, credits a comprehensive study of sports betting policies in Nevada, the U.K. and elsewhere as contributing to the regulations New Jersey landed upon, there is no doubt that the political capital of the state’s commercial casinos carried the day on the matter of who would be licensed as operators.

Though New Jersey will allow as many as 42 sportsbooks to operate online under its licensing structure, those licenses — known as skins — emanate from a core of 14 land-based casinos and horse tracks already doing business in the state, each of which can profit by granting access to other operators.

“Essentially, you took a new business and gave 14 properties a monopoly,” Rebuck said. “There was an investment by those folks for many, many years.”

When William Hill U.S. CEO Joe Asher described the competitive landscape for sportsbooks in New Jersey, and its impact on customer acquisition costs — sportsbooks offer players creatively designed opportunities to play with more cash than they deposit, or even bet the home team at lower risk — Asher jokes that the only one making money on sports betting in New Jersey is the executive who crafted and executed the Devils’ sponsorship strategy, Adam Davis.

It was Davis, chief revenue officer for Devils and Philadelphia 76ers owner Harris Blitzer Sports & Entertainment, who months ahead of the Supreme Court ruling assessed the market and determined that the sportsbook category would work best if the Devils divided it among multiple sponsors rather than delivering exclusivity to one.

The franchise has sold each of them on the idea of a package that delivers on specific objectives, which differ from their competition.

“William Hill came in here and said, ‘How do we let people know who we are and that we’re a trusted brand?’” Davis said. “If you didn’t know who William Hill was when you got here, and you walk on our concourse tonight and see what they’re doing, if you think they’re anything besides a sportsbook you better go see an eye doctor.”

■ ■ ■ ■

In a meeting room at the MGM National Harbor casino resort, about 20 minutes down the Potomac from Washington, D.C., Ted Leonsis revealed his vision to convert a 6,000-square-foot sports bar adjacent to his downtown Capital One Arena into a sportsbook.

“I don’t pay the mortgage six hours a day. I pay the mortgage 24 hours a day,” said Leonsis, owner of the Washington Capitals and Wizards and one of the early advocates of legalized sports betting. “So those of us who own buildings start to say, Sunday, there’s no hockey game. There’s no basketball game. There’s a lot of football games. I’d like to bring 20,000 people in to watch football games and go to our partner’s site and eat and gamble.

“That would be a fantastic reimagineering of what we could do with our building.”

Washington Capitals and Wizards owner Ted Leonsis envisions bringing 20,000 fans to Capital One Arena on off days for NHL and NBA to bet on football games during the season.getty images

There are many reasons to view Leonsis’ vision of a 20,000-seat sportsbook skeptically. The communal experience of fans gathering at an arena to watch their team on TV during a road playoff series does not necessarily predict that they would congregate in large numbers for other games.

But a more modest plan he has to convert the sports bar into a sportsbook clearly has legs.

While D.C.’s regulations allow for such a venture, they aren’t ideal for it. Brick-and-mortar sportsbooks remain a viable amenity for casino patrons and can draw well for big events like Super Bowls, Final Fours and even NFL Sundays. But the day-to-day market has shifted rapidly to mobile, which already accounts for about 80 percent of revenue in New Jersey.

When sports betting comes online in D.C. at a date still to be determined, Leonsis would be better off if the arenas were the only places in the district that could accept wagers, or if a sportsbook that licensed the rights to operate at his arena also could service bettors before and after they walked through his doors.

“On the point of the amount of revenue the district will or will not get, you can have a reasonable debate,” said Grove, the gaming industry analyst and consultant. “I don’t see any reasonable debate around whether the D.C. model is uniquely terrible from a consumer standpoint. There may be ways you could make it worse. But there are far more ways you can make it better.”

While Leonsis doesn’t want to bash what the D.C. Council has authorized, it clearly wasn’t his preference. But he didn’t want to pull his support, risk getting nothing and then watch D.C. politicians lose interest if legislators in Maryland opened before they could.

“I don’t like it,” Leonsis said. “But we just had to politically figure out something to get it going. So let’s keep at it. You know, it’s better to keep the momentum going and get it launched and then have data of what’s really happening, and be kind of the exemplar educator. If it’s not working, you can see it in the real world, where it’s not theory or decks.”

While the specifics of legislation and regulation and the pace at which individual states adopt have garnered the attention of the teams and leagues, some sportsbook operators take a broader view.

“We’ve always felt that this is a very long game, and that most people are looking at it quite myopically, frankly,” said Jim Murren, CEO of MGM Resorts International, which has signed sponsorship deals with the NBA, NHL, MLB and MLS. “I’ve seen more than one report looking at the United States and color-coding the states in terms of when they’re going to approve sports betting and the contours under which they’ll approve it. And we just don’t view it that way.

“I’m not as motivated by or concerned with the pace by which sports betting is rolled out in the United States. I’m more motivated by developing relationships with the fans of professional sports leagues.”

Murren’s position is colored by the fact that sports betting will be a small piece of a larger operation that has increasingly become more focused on getting guests to spend money at its resorts than lose it in its casinos. It doesn’t alter the fact that MGM will lobby for casino-friendly regulation in markets in which it operates. The company has, after all, invested $100 million into a joint venture with global sports betting operator GVC Holdings to develop sports betting products for the U.S. market.

It certainly has to be frustrated by the pace in New York, where it purchased Yonkers Raceway and its Empire City Casino, only to see the state initially limit licenses to on-premises wagering at four upstate casinos, as a more inclusive bill that had momentum in the state legislature was derailed by the governor.

“In the last three months I’ve heard four different times that New York is looking great and New York is looking terrible. It changes with the wind,” said Jason Robins, CEO of DraftKings, which became the market-share leader in New Jersey by being the first to launch its mobile app. “It’s important to be prepared but to not thrash the business with every piece of news that comes out. Part of that is accepting that if we’re fortunate enough that it’s half the [U.S.] population in the next two years, then probably we won’t be able to get up and running in every state in that time. And that’s fine, because then it’s a massive market.”

FanDuel CEO Matt King said his company hasn’t yet seen a state structure so limiting that it would balk at entry, though he concedes that the expense inherent with developing a product for disparate states — for example, a singular app that works in both Pennsylvania and New Jersey without violating the federal Wire Act — could be prohibitive for most operators.

“The short answer is we’ve been dealing with this for years,” said King, who heads the U.S. operation of a company with roots in daily fantasy and pari-mutuel simulcasting, now under global online gaming parent Paddy Power Betfair. “Whether it’s the racing business or the fantasy business, both have very different state-level requirements.

“Adapting a product to individual state requirements creates complexity, and it’s [costly]. We look at it as something that, at our size, we can handle. But some smaller operators might struggle.”

Seeing bills start and stall in many states as legislators attempt to work through conflicting demands, the sportsbooks and sports properties that a year ago slugged it out in several statehouses are increasingly talking about finding common ground in the hope of speeding up the process.

“Say what you want about royalties and integrity fees and data mandates and monopolies — we should be at the table,” said Scott Kaufman-Ross, senior vice president and head of fantasy and gaming at the NBA. “And in most of the states where we are at the table you are able to see a compromise come to bear. I think the legislators that really take the time to understand everyone’s point of view realize this is going to work best if everybody is working together, everyone is incentivized, and everyone is aligned. So let’s get everyone to the table and work it out.”