A few hours before the WNBA’s tipoff on June 21, 1997, then-WNBA President Val Ackerman and former NBA Chief Marketing Officer Rick Welts ran into Jerry Buss, the owner of the NBA Lakers and WNBA Sparks. The scene was the Forum Club at the Great Western Forum, where both Hollywood glitterati and the power elite of the NBA had gathered, along with a capacity crowd, to witness the birth of the WNBA after years of planning.

|

The league’s opening tip ceremony featured President Val Ackerman, Los Angeles’ Lisa Leslie and New York’s Kym Hampton.

Photo by: NBAE / GETTY IMAGES

|

The NBA’s reputation for planning and staging events, then as now, is unassailable. From designing the WNBA logo to creating its signature orange-and-oatmeal ball, all the details were final — except one: Exactly who was singing the national anthem before the league’s inaugural game?

“We walked up to Jerry,” recalled Welts, now president of the Golden State Warriors. “He said, ‘I want to introduce you to Miss April. She’ll be singing The Star-Spangled Banner.’”

The NBA’s New York office was summoned. A centerfold participating in the groundbreaking game for a new women’s league definitely was not part of the plan.

“Suffice it to say, Miss April did not sing the national anthem,” said Welts. An orchestral recording did the job instead.

With the WNBA now beginning its 20th season, the NBA’s goal of operating a leading women’s sports property stands as intended. The initial eight-team league has become a league of 12 teams, and the WNBA has become a staple of the U.S. sports landscape. It has a TV deal with ESPN that runs through 2025 and, under terms that begin next year, will bring the league roughly $25 million a year. Nike’s new $1 billion on-court deal with the NBA that begins in 2017-18 includes a major investment in the WNBA, as well.

“The commitment that ESPN has made and Nike has made going forward makes me confident that we are not swimming against the stream and that we are becoming more part of the mainstream sports culture in the U.S.,” said NBA Commissioner Adam Silver, who helped launch “the W” when he was president of NBA Entertainment in 1997.

That’s not to say challenges don’t exist.

Ackerman was president for the league’s first eight years. Since then, the WNBA has had three more presidents: Donna Orender, 2005-10; Laurel Richie, 2011-15, and, starting this year, Lisa Borders. Attendance last year slid to an all-time low, television ratings have slipped (last year brought a double-digit drop on ESPN) and profitability remains elusive.

At the local level, franchises have come and gone. Only three of the league’s original teams — the Sparks, the New York Liberty and the Phoenix Mercury — remain from the initial eight.

Borders, the new WNBA president and a former vice president of global community affairs at Coca-Cola, is promising to focus on growth opportunities (see story, Page 27). And while Silver last fall said he expected the WNBA would be further along as a league at this time than it is, he said the NBA is firmly committed to the women’s game.

“We feel very optimistic,” he said. “We are doubling down, and the marketplace is responding.”

ROOTS OF THE W

Optimism was also in abundance when the WNBA began play in 1997. For years, the NBA had been discussing the creation of another league. Former NBA Commissioner David Stern recalls commissioning a study in the early 1990s to determine whether a women’s league could be viable.

If the U.S. women’s national team had won the first of its uninterrupted, consecutive Olympic gold medals in 1992 instead of 1996, the WNBA would have a longer history.

“We certainly would have hustled a lot if the women would have won gold in Barcelona,” Stern recalled. (The team took bronze in ’92.)

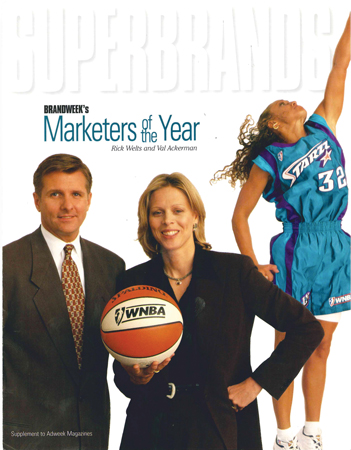

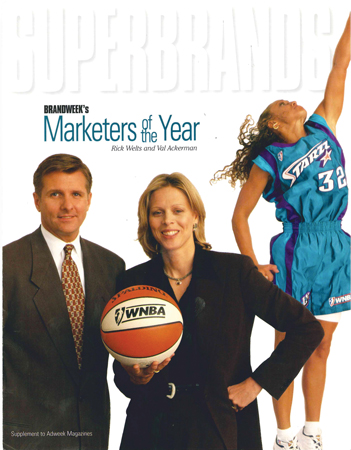

|

Rick Welts and Val Ackerman drew praise from Brandweek in ‘97.

|

Those early conversations included the notion of a men’s minor league and perhaps taking over the now-defunct Continental Basketball Association. Some of those ideas eventually morphed into the NBA D-League.

“Behind all of those ideas was that we had owners with empty arenas in the summer,” said Steve Mills, general manager and executive vice president of the New York Knicks who at the time was an assistant to then-NBA Deputy Commissioner Russ Granik. “The success of the 1996 Atlanta Olympics team made the women a hot property, so that’s what we launched.”

Ackerman, a three-year captain of the University of Virginia basketball team, recalled that the NBA’s first link to women’s basketball was sponsoring the Women’s Basketball Coaches Association’s annual Final Four reception, which began around 1990. “That got women’s basketball on the [NBA] radar screen,” said Ackerman, now commissioner of the Big East Conference.

As the NBA worked more closely with USA Basketball, the sport’s national governing body, the idea of supporting a women’s elite squad, just as the league had nurtured the 1992 men’s Dream Team for the Olympics, began to coalesce. Convincing two-time NCAA champion Stanford coach Tara VanDerveer to go on hiatus and coach the U.S. women’s national squad gave the team credibility and allowed it to grab some of the best players for a then-unheard-of sum of $50,000, including Lisa Leslie, Sheryl Swoopes and Dawn Staley. Many were playing in Europe. UConn stalwart Rebecca Lobo joined the team as a rookie.

“The WNBA had the backing of three networks and the NBA, so we thought this was the first time a women’s league had a chance to last.”

JOHN LEBBAD

Former brand director, Sears

Ackerman and others at the NBA worked with USA Basketball to plan a 10-month pre-Olympic tour that would span 1995-96. USAB initially was reluctant because of the $3 million cost. But here was an early sign of the NBA’s support for the women’s game: Stern agreed to cover any shortfalls. Team USA won all 52 games of that tour, and the NBA sold sponsorship, merchandising and TV rights — which more than covered costs.

“We made a little money, and the tour became the foundation for the WNBA,” Ackerman said.

Accordingly, the NBA homed in on creating the WNBA, even prior to the 1996 Olympics. The NBA’s board of governors approved the concept of the WNBA in April 1996.

“There was never a minute’s worth of discussion about a name other than the WNBA,” Ackerman said. “It was about year-round basketball, use of NBA infrastructure and arenas in the offseason, the possibility of overlapping fan bases, and connecting with women in a new way.”

OLYMPIC HOPEFULS

The U.S. women’s basketball team was on the cover of Sports Illustrated’s Olympic preview issue in July 1996. After sweeping the tour, the team won all eight games on its way to the gold medal in Atlanta, with each of the U.S. women’s games drawing more than 25,000 fans in Atlanta. After nearly 33,000 fans watched the U.S. beat Brazil for the gold medal at the Georgia Dome, it was clear the WNBA at launch would be a cause as much as a brand extension.

“We were able to sell something that wasn’t a sport yet,” said Gary Stevenson, another WNBA architect who at the time was president at NBA Properties. Today, he is president and managing director of business ventures at MLS. “It was a movement,” Stevenson said.

Added Welts: “There couldn’t have been a better springboard. The WNBA became, thanks to Atlanta, this kind of cool thing for corporate partners.”

But even before it had corporate sponsors, players or teams, the WNBA had TV deals with incumbent NBA rights holder NBC, with Lifetime and with ESPN, which desperately wanted NBA rights.

|

The WNBA built from the success of the 1996 U.S. Olympic women’s basketball team.

Photo by: GETTY IMAGES

|

Sears was one of its earlier sponsors. The company was already heavily invested in women’s sports, including having sponsored the USAB women’s tour. “The WNBA was a natural extension,” said John Lebbad, a former Sears brand director and now chief marketing officer at RV dealership Lazydays. “The WNBA had the backing of three networks and the NBA, so we thought this was the first time a women’s league had a chance to last.”

Sears, which remained a sponsor through several of the league’s early years, saw lifts in store traffic and brand perception that it attributed directly to its involvement with the W.

Other blue-chip brands were also quick to sign on, including Kellogg’s, American Express, Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, Nike, Reebok, Adidas and Champion. Aside from the post-Olympics buzz, sponsors got three-year packages that were nearly ambush-proof.

Anheuser-Busch was another early WNBA sponsor, for its Bud Light brand. While former A-B sports media and marketing chief Tony Ponturo said the company felt then that it was the beginning of a growth curve for women’s pro sports, there was another reason it wanted a deal with the W: Miller Brewing Co. was an entrenched NBA sponsor. A-B wanted in.

“I would say the WNBA is exactly where it should be. Work continues to need to be done on ticket and sponsorship sales, but it’s a great success.”

DAVID STERN

Former NBA commissioner

“We didn’t wait for a proposal,” Ponturo said. “We knocked on David Stern’s door first and sent a simple message that we wanted to be a WNBA sponsor with Bud Light and prove to them what kind of good sponsor we could be, not only for the WNBA, but for the NBA down the road as well, which came true.”

Ponturo recalls paying upward of $3 million a year for WNBA rights. However, a focus group held eight to 10 years after the league was launched during which women were asked if a WNBA sponsorship would engender loyalty to Bud Light is something Ponturo remembers more vividly.

“Basically, their answer was no, which was surprising and frustrating,” Ponturo recalled.

A-B is still a WNBA corporate patron, but it also has NBA rights.

Agent Leonard Armato recounted a similar experience when he asked Nike to produce a signature sneaker for player client Lisa Leslie, who won three WNBA MVPs and two championships to go with her four Olympic gold medals.

“The guys at Nike told me, ‘We love her, but nobody is buying shoes because Lisa Leslie is wearing them. They are buying them because Michael Jordan is wearing them,’” Armato said.

FACE THE CHANGES

The hard truth was that as the WNBA became more established as a basketball league, it lost some of the gloss from the ’96 Olympics. The league’s second-year attendance mark of 10,864 fans per game, in 1998, has never been equaled. So while the level of talent in the W today is considered by basketball experts to be better than ever, the players are competing at a time when the media and sponsorship market is cluttered.

The two decades since the launch of the WNBA have also brought the explosive popularity of the U.S. women’s national soccer team and subsequent women’s pro leagues in that sport. While good for the overall platform of women’s sports compared to 20 years ago, such gains have made the WNBA less distinct.

There are no current WNBA corporate sponsors that aren’t NBA rights holders.

“It is really hard to sell sponsorships to big brands if you are a niche sport,” said Phil Guarascio, the former vice president of corporate marketing at General Motors, another original WNBA sponsor.

|

Former NBA Commissioner David Stern with Chicago’s Michael Alter and Margaret Stender

Photo by: AP IMAGES

|

Guarascio said GM was involved with the WNBA largely to help establish a Detroit franchise, which became one of the league’s first expansion teams in 1998. That franchise proceeded to win three championships (2003, 2006 and 2008) but relocated to Tulsa, Okla., in 2010 and this year moved again, to Dallas.

In the early years of its WNBA deal, GM was buying upward of 5,000 seats per game in Detroit in what Guarascio said was a successful promotion to build traffic at auto dealers. As for a strategy for today’s WNBA? “At this point, they need to go all in for a title sponsor who would do their marketing for them,” said Guarascio, who spent seven years as the NFL’s lead marketing and sales executive after leaving GM. “I’ve also had people tell me they would rather watch NCAA [women’s basketball], so you wonder about a model that could attract fans of both.”

Acknowledged Ackerman: “It was a blessing and a curse that we came out of the gate so strong. When we started the league, David [Stern] put tremendous marketing weight behind the launch. Great sponsors were spending incrementally. We had three games a week on national TV and they were doing their own national campaigns. That probably wasn’t something that was going to be repeated, but my notion is that can’t stop, especially now, because the landscape is more crowded now than when we started.”

As the league moved through its early years, it also found a need to change its approach to franchise ownership. The league debuted with a single-entity structure, in which the original eight clubs were owned by the league but were operated by their same-market NBA teams. With the W operating at a loss in those early years, the NBA made the decision to allow for outside investors — a decision that also would enable the league to expand outside NBA team markets.

“The thing we got wrong was the central structure of selling the league,” Welts said. “Over time, we realized that teams, as always, are better to execute it.”

The change brought to the WNBA the Connecticut Sun, the league’s first independently owned team, in 2003. The Chicago Sky followed, debuting in 2006.

Both teams are part of the WNBA’s current roster of 12 teams, with four others also having independent, non-NBA team ownership: Atlanta, Dallas, Seattle and Los Angeles.

The NBA also mistakenly believed at launch that NBA fans would migrate in the summer over to the WNBA. The first year, the WNBA drew an average of 9,662 fans per game, followed by the 1998 record attendance year. But the league has since seen its average attendance dip to last year’s all-time low of 7,318 fans per game and it has not averaged more than 10,000 fans per game since 1999. Meanwhile, the NBA is enjoying record attendance.

Which of the following organizations has done the most to support and encourage women's athletics in the United States?

| NCAA |

33% |

| U.S. Soccer |

26% |

| WNBA |

16% |

| U.S. Olympic Committee |

6% |

| WTA |

5% |

| LPGA |

4% |

| Not sure / No response |

10% |

Source: Turnkey Sports Poll, April 2016. The survey covered more than 2,000 senior-level sports industry executives spanning professional and college sports.

“We discovered that the core fan for each was different,” Welts said.

But some NBA teams continued to see value as the W evolved.

“We had a new facility and we were interested in in-arena activities,” said Lawrence Payne, executive vice president of corporate partnerships, broadcasting, brand and content for Spurs Sports & Entertainment, which bought the WNBA’s Utah Starzz and relocated the franchise to San Antonio in 2003. The Stars will again share AT&T Center with the NBA Spurs this year.

“The W made great sense,” Payne said. “It was during the summer, and there was a new building in Houston and competition in Dallas. We knew we had to gear up. If we didn’t do it, there was a chance someone else would.”

And the Spurs are not alone. Other NBA teams view the WNBA similarly. The Warriors, for example, are interested in a WNBA franchise since they have a new arena opening in 2019.

“We are bullish,” Welts said. “We very much want to make it happen here.”

DEFINING SUCCESS

As its 20th season opens, defining success for the WNBA is tricky. Stern, Ackerman and other founders note that it took the NBA 27 years to reach an average attendance of more than 10,000.

“The WNBA’s legacy is its longevity,” said Ackerman, recalling a dozen or more prior attempts at women’s pro leagues that failed. “Anyone associated with the WNBA needs to be very proud, because this league is absolutely a beacon for women’s team sports.”

Ponturo said he expected more.

“From a vantage point of 20 years ago, I would have thought it would have grown bigger than it has,” he said.

Armato, and others across the industry, sounded a similar chord. “The NBA has done an amazing job of propping it up,” he said. “I don’t think it today is as successful as anyone would have hoped. Not even close.”

Which of the following would have the most significant impact on the WNBA's growth as a property?

|

|

2016 (2006)* |

| Focus on increasing game attendance |

29% (18.3%) |

| Nothing to do; the property has peaked |

27% (39.8%) |

| Increase TV ratings |

26% (18.0%) |

| Secure additional team and league sponsors |

5% (6.0%) |

| Improve the quality of play |

5% (13.7%) |

| Not sure / No response |

8% (NA) |

* The 2006 results came from a polling effort through the SportsBusiness Journal/Daily website. The following question was asked: How can the WNBA most develop as a property? The same response options that appear here were presented in 2006 (with the exception of Not sure/No response), and the survey drew 350 responses.

Source, 2016 data: Turnkey Sports Poll, April 2016. The survey covered more than 2,000 senior-level sports industry executives spanning professional and college sports.

Stern counters that view.

“Obviously, it helps that the WNBA had an older brother that was stubborn and motivated,” he said. “I would say the WNBA is exactly where it should be. Work continues to need to be done on ticket and sponsorship sales, but it’s a great success. The WNBA’s demise was widely and continually predicted, and it’s now a staple on the landscape of professional sports.”

Consider that the American Basketball League, which launched a year earlier than the WNBA and attracted many name players by offering higher salaries than the WNBA, lasted fewer than three seasons.

“We never had the rich uncle, but I’m glad they are still around,” said ABL co-founder and former CEO Gary Cavalli, who still treasures his 1997 ABL All-Star Game ball, signed by the likes of Jennifer Azzi, Dawn Staley and Kate Starbird. Cavalli is now semi-retired and teaching at Stanford after 14 years as executive director of the Foster Farms Bowl. “The bottom line is that they chose to support the WNBA because they recognize how important it is to have a women’s league,” Cavalli said, “so I salute them for that.”

Stevenson called the WNBA very successful.

“If the NBA spends millions or whatever they lose on the league, is there a better way to spend your marketing dollars than to help fill your arenas in the summer when they are usually empty; to help introduce a whole generation and gender to basketball; and to have basketball talked about year-round by all those groups? Those are all immensely valuable things,” he said. “The WNBA has fulfilled those missions, and now young girls dream about playing in the WNBA. I have nieces who wanted to be Rebecca Lobo. Before, they wanted to be like Michael Jordan. You can’t put a price on that.”