|

Photo by: AP IMAGES

|

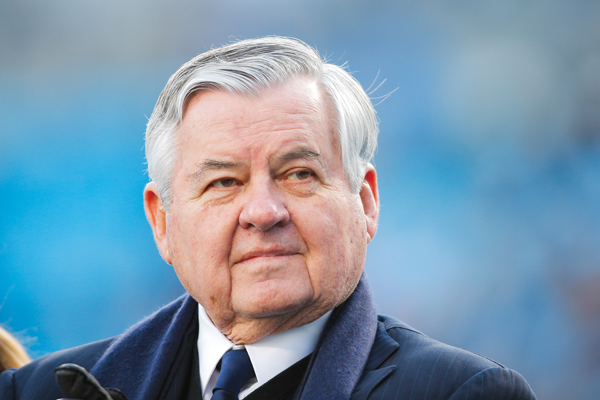

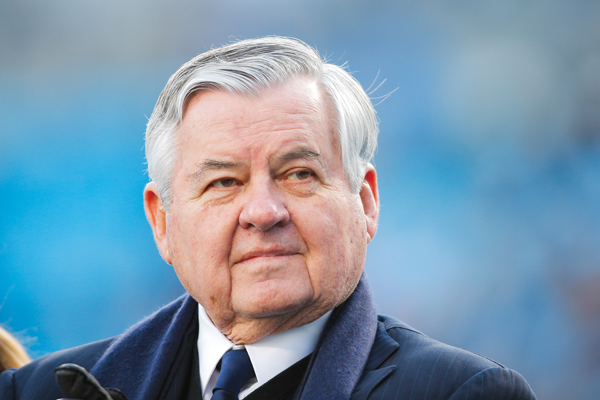

Jerry Richardson had been on the field to accept the NFC championship trophy in front of a raucous home crowd, then to the locker room to see his players, then back up to his end zone suite to celebrate with family and a few close friends.

Returning ahead of most of his guests, the Carolina Panthers’ 79-year-old owner settled onto a tall stool, sighing from the ache of a knee that is now bone-on-bone, his penance for being only the second NFL owner to have played in the league.

THE CHAMPIONS

This is the final installment in the series of profiles of the 2016 class of The Champions: Pioneers & Innovators in Sports Business. This year’s honorees and the issues in which they were featured are:

■ Jan. 18: Roger Penske

■ Jan. 25: Lesley Visser

■ Feb. 8: Jeremy Jacobs

■ Feb. 22: Bob Lanier

■ March 7: Joseph Cohen

■ March 21: Jerry Richardson

Richardson placed the NFC championship trophy on the high-top table next to him, then gestured for retired Bank of America Chairman Hugh McColl to join him. It had been a night of spectacular joy for both men, the entrepreneur who overcame long odds time and again to reach this evening, first to build a fortune and then to land the team, and the banker who stood by his side going back to when both were starting.

In a rare departure from his often stoic public demeanor, Richardson consented to bang the massive drum that the Panthers roll onto the field before home games. In a more typical move, he invited McColl to serve as the game’s honorary captain.

They watched the game from the suite together, Richardson sitting quietly while McColl hooted and hollered, then took the stage side-by-side as the Panthers accepted the trophy.

Home games were among the few times the old friends saw each other during what turned out to be the best season in the franchise’s history. Giddy over the Panthers’ success, McColl called several times, hoping to set up a lunch. Each time, the response from Richardson’s assistant was the same.

“He was never around,” McColl said. “He spent the season sweating over L.A. Put a huge amount of time into that. Every time I called, he was out of town. He goes and sees people. He went all over the place. Meet, meet, meet, meet, meet. That’s his way.”

While the Panthers rolled to a 14-0 start that captivated the Carolinas, Richardson spent much of his time and energy fretting over the selection of a stadium for another owner in a city 2,000 miles away, head heavy with the responsibility of corralling support for the outcome he thought was best for the league.

Jerome Johnson

‘Jerry’ Richardson

■ Age: 79

■ Hometown: Spring Hope, N.C.

■ Resides: Charlotte

■ College: Wofford College

■ Family: Wife, Rosalind; sons Jon (deceased) and Mark; daughter Ashley; nine grandchildren; one great-grandchild

NFL playing career

■ 1958 NFL draft: Selected 154th (13th round) by the Baltimore Colts

■ Games played: 23 total during the 1959 and 1960 seasons

■ Position: Flanker (No. 87)

■ Catches: 16

■ Yards: 183

■ Touchdowns: 5

■ Highlight: Caught a 12-yard touchdown pass from Johnny Unitas in the fourth quarter of Baltimore’s 31-16 victory over the New York Giants in the 1959 NFL Championship Game. (Editor’s note: The career statistics above include that postseason appearance.)

It has been this way since the group led by Richardson won the expansion franchise in 1993.

Never a member of the NFL rank and file, Richardson chaired the first committee he ever served on, created to help his fellow owners rally support and funding for state-of-the-art stadiums such as his. Within a few years he was on the league’s labor committee, which he later would chair. He also would co-chair the search committee that selected Roger Goodell as NFL commissioner.

“His ability to lead starts with his own personal qualities: the integrity, the openness, the candor,” said Paul Tagliabue, the former NFL commissioner who turned to Richardson on important issues from the start. “He has an ability to talk to everybody — even the people he disagrees with. He has an ability to anticipate what the big problems are going to be and what the manageable positions are going to be. All of those qualities are very valuable.”

Back in the suite after the NFC championship game, with rows of glasses filled with champagne waiting on a nearby table, Richardson gathered his family for a photo with the trophy.

“Roz and I have bought a lot of silver over the years,” Richardson said, leaning into his wife Rosalind. “But none this expensive.”

From halfway across the suite, McColl interjected.

“Fo’ hundred million dollahs!” he yelled, just in case anyone had forgotten.

The Richardson clan laughed, none harder than the man holding the trophy.

BUILDING A BASE

McColl was a young loan officer at a Charlotte bank, only a year or two out of college, when a friend introduced him to Richardson, a former NFL player who had gone in with a college teammate, Charlie Bradshaw, on the first of what they hoped would be a chain of hamburger stands.

Richardson’s story was a compelling one.

Wire thin at 6-foot-3, Richardson was not recruited out of his small-town North Carolina high school. He got a chance to play college football only because his coach drove him four hours to try out in front of a friend at tiny Wofford College in Spartanburg, S.C. He took a partial scholarship and became a star, excelling as a receiver while also playing safety, returning kicks and punts, and kicking field goals.

|

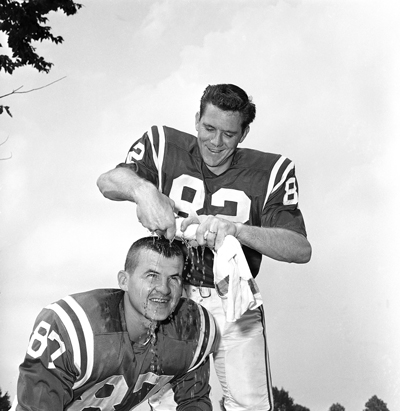

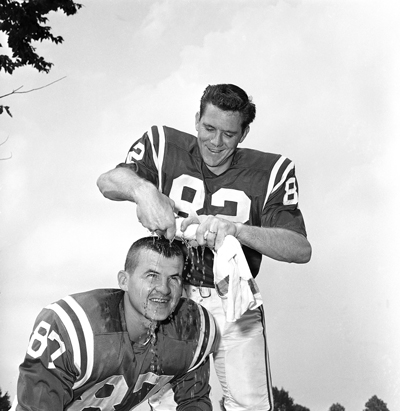

Future hall of famer Raymond Berry has some fun with fellow Baltimore Colts receiver Richardson (No. 87) in the early ’60s.

Photo by: AP IMAGES

|

Drafted in the 13th round by the Baltimore Colts, Richardson reported to training camp in the summer of 1959. His first meeting was in the basement of a college dormitory, where a long board on the wall listed all the players by position. There were 19 wide receivers, topped by eventual hall of famers Raymond Berry and Lenny Moore. His coaches told him they only intended to keep three.

“A real confidence builder,” Richardson says today, cackling.

Yet Richardson made the roster. Then, in the fourth quarter of a rematch against the Giants in the NFL championship game, he caught a 12-yard touchdown pass from Johnny Unitas that put the Colts ahead 21-9.

He was on his way to what many say would have been a long and productive NFL career. But an NFL career then wasn’t what it is today, particularly when it came time to check your bank balance.

After Richardson’s second season, the Colts offered him $9,750 to return for a third. He wanted $10,000. He had two small children at home and a third on the way, and the psychic value of breaking through to five figures meant far more than the $250 difference.

When the Colts refused, Richardson walked away, choosing instead to use the proceeds from a $4,674 bonus check he’d received from the championship to go into business with Bradshaw. They opened their first Hardee’s in Spartanburg late in 1961 and soon after hoped to open a second in Charlotte. That’s how Richardson found himself having breakfast with the young banker who would become a lifelong friend.

At that time, a Hardee’s franchise could be built and outfitted for about $25,000. McColl agreed to lend them the full amount. Soon after, he extended the loan to cover another store, and then another and another, until he’d given them the $100,000 maximum that his bosses would allow.

The banker chuckles when asked about the prescience of the large bets he made on Richardson’s fast-food business, which would take off in the ’60s and ’70s.

“I didn’t know [anything] about the business, OK,” McColl said. “But what I do know about is people.”

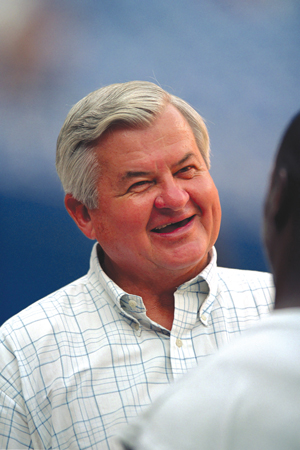

|

Jerry Richardson, sharing a laugh with NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell, has been a go-to league leader since founding the Panthers in 1995.

Photo by: HUNTLEY PATON

|

Over the years, Richardson often invited McColl to his stores. Rather than simply presenting a business plan on paper, he liked to show his banking friend the operation at work.

“What impressed me the most about Jerry — then and still — he knew his employees by name,” McColl said. “He got in there and cooked with them. He picked up trash. He’d come in to the manager with a bag or a cup and say, ‘I picked this up in the lot.’ Which of course meant, ‘Why didn’t you clean it up?’ Not why didn’t you send somebody.

“He had the capability of motivating what you would think of as low-wage earners. Jerry’s people all knew him and liked him. So I really bet on him because I believed he was a good leader. He didn’t have the theoretical skills that you read about in business school. But he had the people skills. The leadership skills.”

In July 1976, after growing to 21 franchises, Richardson and his partner took their company public, debuting on the New York Stock Exchange one month before either of them turned 40.

They celebrated with their wives at 21 in New York, blissfully unaware of the frustration that awaited them. The company they called Spartan Food Systems, based in Spartanburg, would soon be purchased by the larger conglomerate Trans World Corp., which included holdings such as Trans World Airlines, Hilton and Century 21.

While it increased his wealth, this was the beginning of a trying span for Richardson, who saw his company assailed by corporate raiders, hacked into pieces and reassembled in ever-changing configurations that he was left to oversee, with an increased cash-flow burden brought on by massive debt. Eventually, the company was taken over by private equity firm Kohlberg, Kravis, Roberts & Co., setting the stage for Richardson to begin the next stage of his life.

“He went through a terrible period, where you fall into the hands of pirates who strip companies of their assets, pile up the debt, put it in their pocket and leave,” McColl said. “Jerry wasn’t prepared for that emotionally or intellectually. He built it and somebody tore it apart, and then they left him to run something that was staggeringly bad.

“It was painful for him. But he worked his way out of it. KKR bought him. And it was after that second or third iteration that he came to me and said, ‘I want to get a football team.’”

GETTING A TEAM

Richardson’s quest for an NFL team percolated, as pursuits often do, bubbling up through his experiences and the connections of his life.

Playing in the league for a franchise that owner Carroll Rosenbloom built into a champion from scratch; seeing the NBA plant its flag in Charlotte, 75 miles up I-85 from his Spartanburg home; traveling in what his longtime friend McColl calls the “owner class” as he presided over a publicly traded conglomerate — they all played a role.

But if you had to pick the moment of germination, it might have been during one of his many conversations with iconic former NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle, who Richardson came to know well when he lived in Newport Beach, Calif., for a couple of years after his company bought the Denny’s chain, which was based there.

Richardson picked Rozelle’s brain about the inner workings of the league for hours at a time, storing away information about league relationships and politics that would serve him well when he did succumb to the urge to pursue a team.

“He would tell me all the nuanced things that would be helpful to me about ownership, and ways to contact people,” Richardson said. “He was just tremendous to me.”

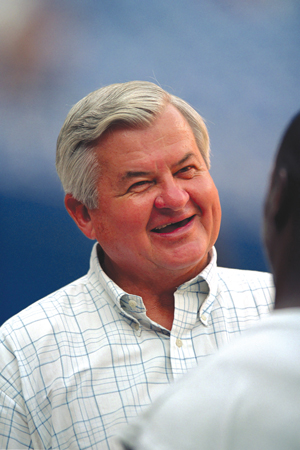

|

The Panthers’ owner has a laugh on the field before a game in 2000.

Photo by: GETTY IMAGES

|

It was around 1987, as he rode out a tumultuous period for his company, that Richardson started floating the pursuit among close and influential friends. One of his first calls was to McColl.

“I thought, ‘Aw, hell, this is a pipe dream,’” McColl said during a recent conversation at his Charlotte home. “That can’t happen. But he’s my friend. I’ll go along.”

Another he spoke with was Joab Lesesne, retired longtime president at Wofford College, where Richardson long has been a prominent benefactor, serving on the board for more than 35 years.

“I sort of laughed, you know,” said Lesesne, who became friends with Richardson as a young history professor and turned to him as a confidant when he moved into college administration. “But when Jerry tells you he’s going to do something, you better not blow it off. I never thought he’d put together a company that ended up on the New York Stock Exchange, either. He had that dogged determination.”

Richardson had a different vision than most NFL owners at that time. Not only did he want a team, he intended to play in a new football-only stadium. Seeing the trend in baseball, where Camden Yards had ushered in a new era, he predicted that the NFL would need a new football-specific model — and a new way to pay for it.

Richardson planned to finance the stadium privately, backed by loans. But he knew he’d also need a way to generate substantial cash up front. One of his attorneys, Louis Howell, suggested that they could attach a mandatory payment to the right to buy season tickets, similar to the way that many college programs tied season tickets to a minimum donation. From that idea came what the Panthers marketed as a permanent seat license, or PSL.

Compare the ownership group’s early projections to its eventual startup costs and you wonder how Richardson kept enough momentum to land the franchise.

His group thought the stadium could be built for $87 million, or about the amount they raised from PSLs. It came in at $200 million. They projected the expansion fee to be $50 million. It turned out to be $140 million. They anticipated TV revenue of about $30 million annually, but the NFL limited them to about $13 million for each of their first three seasons.

“We were missing all these numbers,” Richardson said. “But we just kept plugging away and plugging away and plugging away.”

While Richardson was corralling support locally, Rozelle made a call that put him on the map in a meaningful way with the league. Not long after Tagliabue took over for Rozelle as commissioner in 1989, he said emphatically that he would make expansion a priority.

“Right after I said that, I heard from Pete Rozelle,” Tagliabue recalled during a recent conversation. “He said that Jerry Richardson was a special person, someone Rozelle had spent a lot of time with and had great respect for, and I should make the time to visit with Jerry whenever that opportunity would present itself.

“Jerry spent dozens if not hundreds of hours talking to Pete Rozelle about the NFL. The structure of the league. The values of the league. The pitfalls as well as the potential to be an influential leader. … The amount of time he spent with Pete Rozelle told me the sort of owner he was going to be.”

At a meeting in Chicago on Oct. 26, 1993, five expansion finalists — Baltimore, Charlotte, Jacksonville, Memphis and St. Louis — made their presentations to NFL owners. Each group had 30 minutes.

|

Usually opting to stay out of the spotlight, Richardson agreed to beat the Panthers’ honorary “Keep Pounding” drum before the NFC Championship Game in January.

Photo by: AP IMAGES

|

Richardson was joined by marketing consultant Max Muhleman and Mike McCormack, a well-regarded football executive who would serve as the team’s first president and GM. After each of them spoke, Richardson took his turn.

“One of the things I recall was that they told me to stay on the podium,” Richardson said. “And I didn’t stay on the podium. I walked off the podium and went to owners and talked to the owners. I wanted to look at them. And I’d seen most of them enough that I wasn’t uncomfortable doing it.

“Seven and a half years is a long time. Other groups would get in and drop out. Get in and drop out. Get in and drop out. And we stayed the course.”

As always, the meeting room was set up in a horseshoe, with owners ringing a vacant center.

“He got right into the middle of the horseshoe and started talking about how everything he has he owes to the National Football League,” said Joe Browne, who recently retired after 50 years as a senior executive at the league. “And he’s looking each owner in the eye, going from individual to individual, saying that the NFL is everything to him.”

“The NFL gave me my start,” Richardson told the owners. “Everything that my family has and I have now, I owe to the National Football League.”

After the presentations, the Carolina contingent was escorted to a dimly lit holding room, with no promise that they would get an answer that night. Richardson figured resolution might be approaching when Bears owner Ed McCaskey passed through on his way out of the conference room. McCaskey said “Congratulations,” and then kept going.

Whether that congratulations was for simply making a solid presentation or for actually getting a team, Richardson wasn’t certain. When Tagliabue approached the table at which he was waiting and extended a hand, he knew for sure.

“Jerry, congratulations,” Tagliabue said, “You have been awarded the 29th franchise in the National Football League. We don’t have much time. We’re going to announce it now.”

Two minutes later, Richardson was in front of a room filled with TV cameras and reporters.

He had earned the right to grow a franchise from its seeds — something he’d done before.

A LEAGUE MAN

With an afternoon kickoff at home against the Green Bay Packers only 10 minutes away, Richardson strode slowly off an elevator and into the owner’s box.

Inside, his wife of 57 years entertained many of their oldest friends. For one game each year, Richardson gathers a core of pals he has stayed in touch with since grade school. On this afternoon, they invited a handful of Rosalind’s childhood friends, too.

Standing at the doorway, Richardson looked somber.

While his guests enjoyed their reunion, Richardson was in his stadium office, meeting with Packers CEO Mark Murphy and former San Francisco 49ers executive Carmen Policy, the latter of whom was spearheading the Carson stadium venture that would have moved the Oakland Raiders and San Diego Chargers to Los Angeles, the option that Richardson preferred.

Richardson’s role as one of the leaders of the L.A. committee was only the latest in 20 years worth of key appointments that cemented him as a power broker in the league, a role that was foreshadowed at his very first owners meeting, when Pittsburgh Steelers owner Dan Rooney and the New York Giants’ Wellington Mara invited him to join their traditional place in the room’s back corner.

“He’s very much a league man, and a good one,” said Rooney, who showed Richardson the ropes as an owner and helped usher his rapid ascent at league meetings. “Sometimes he disagrees with the league and sometimes we disagree. But you know he’s trying to do what he thinks is best for the league.”

This isn’t to say Richardson doesn’t care about the grass in his own yard. His fingerprints are all over the franchise. On walls and tables throughout the Panthers’ offices and players’ areas, you will find prints that carry five core principles he long has stressed to his employees — hard work, harmony, teamwork, listen, respect — all written in his hand, an homage to the notes he left on napkins when he visited his fast-food franchises.

Before changes in security measures made it difficult, Richardson was known to make the rounds through the stadium parking lots in a golf cart, picking up fans who looked like they needed help getting to the gates. Even after the changes, he continues to drive laps around the stadium, showing visiting owners around, often stopping to check on his customers and press flesh.

“He just has a certain presence about him, a certain dignity coupled with friendliness,” said John Mara, the Giants’ co-owner whose father Wellington became one of Richardson’s close friends. “He’s also somebody who has complete integrity. When he looks you in the eye and tells you something, you believe him right away. And he’s a man of principle. I can’t say how much I admire and respect him. He commands everybody’s attention.”

There was never greater evidence of that than the dogged way in which he operated while heading the owners’ labor committee.

On a Friday morning early in the negotiation that led to the lockout of 2011, Richardson sat down at a desk at the edge of his kitchen, a pad and felt-tipped pen placed within reach of the phone. To his left rested a binder filled with business contacts, including office, home and cell numbers of the owners of the other 31 NFL teams. As chair of the league’s labor negotiating committee, Richardson intended to spend the morning nurturing consensus.

A day earlier, he had assigned each of the 10 owners on the committee to call two other owners to update them on discussions as they crafted a labor proposal. But, truth be told, he wasn’t sure that they’d do it without coloring the conversation to suit their own aims.

So Richardson took a seat next to the phone and began dialing. For each call, both outgoing and incoming, he marked a tally. By the end of the day, there were 58.

The next morning, a Saturday, he took his place at the desk and resumed his work, again logging each call. By day’s end, the count was 38.

On Sunday, he began again. He was on his 17th mark when his wife, Rosalind, intervened.

“You can’t do this anymore, Jerry,” she said.

And that was that, if only for that day.

“[Revenue sharing] was a big, big acrimonious issue, the most contentious issue in the league,” Richardson said. “The revenue-sharing people had an agenda. The high revenues had an agenda. You had new stadiums being built. New debt structure. It was very, very difficult.

|

Richardson, shown before a game in 2006, says, “The NFL gave me my start.”

Photo by: GETTY IMAGES

|

“If I was talking to Al Davis, I’d say, ‘Al, we gotta reach some common ground.’ Talk to Jerry Jones, ‘We gotta reach common ground.’ Jerry Jones flew with me to Cincinnati to meet with Mike Brown, to spend an afternoon talking about revenue sharing. But the goal was to get Jerry and Mike together, to go out and talk for four hours. Now, that takes time. And it takes energy.”

Keep in mind that this was a labor process so protracted, Richardson started it with a bad heart and finished it with a transplanted one.

When Richardson entered the league, Tagliabue encouraged him to spend time with union head Gene Upshaw, hoping that their shared experience as NFL players might help them build a working relationship.

“I thought putting them together could be extremely positive,” Tagliabue said. “I think Jerry’s qualities as an individual attracted Gene. His honesty. His openness. His candor and reputation as a straight shooter. All those things that are sometimes missing in relationships with union leaders and employers. But Gene understood very quickly that Jerry was different and that he could rely on him. If he said he would work with the commissioner to get something done, Gene could take that to the bank.”

For years, Upshaw had been calling for teams to open their books to the players. So when they met, Richardson brought the Panthers’ financials. Each year, he’d update Upshaw with the team’s latest reports.

So it was that Richardson took the Panthers’ latest numbers with him when he went to Washington to see Upshaw on an overcast afternoon in April 2008.

Seated across a table from each other in a Ritz-Carlton smoking lounge, Richardson shared a financial forecast that had the Panthers headed for a cash call if they continued under the framework of a CBA they had negotiated only two years earlier — a deal that Richardson had championed, encouraging fellow owners to embrace “labor peace at any price.”

“This is not working for the Carolina Panthers,” Richardson told Upshaw. “We need to do something. You and I need to figure out some way to avoid major labor conflict, because I’m telling you, I will not do labor peace at any price anymore. And I’m not telling the commissioner to tell you. I’m telling you.”

Upshaw looked Richardson in the eye and responded with a calmness that was surprising, considering his words.

|

Richardson, with the Browns’ Jimmy Haslam, often drives visiting owners around in a golf cart.

Photo by: HUNTLEY PATON |

“We will not give back one [expletive] dollar,” he said.

Richardson was taken aback. He saw Upshaw had dug in, and realized that pushing him would only yield greater resistance. So rather than continuing the discussion, Richardson gathered his things.

When Upshaw asked what Richardson intended to do about the impasse, he responded that he would report it to the then-new commissioner, Goodell, along with a recommendation that they opt out of the agreement.

Upshaw chuckled at the prospect.

“The players are chomping at the bit for you to opt out of the agreement because you’ll have an uncapped year,” Upshaw said. “And you can’t get 24 votes anyway, because the owners don’t want to deal with an uncapped year.”

“We’ll see,” Richardson said. And he left.

The owners convened in Atlanta soon after to discuss their course of action. Goodell spoke briefly. Then Richardson laid out the details of his meeting with Upshaw. As promised, he recommended they opt out of the deal. He also told them that Upshaw said he’d never get their support.

Not only did they vote 32-0 to opt out, they voted 32-0 to lock out. They agreed 32-0 on the terms they would present to the players and voted 31-1 in favor of a second package they would accept as a compromise.

It all took barely an hour.

“You have all these teams that compete like crazy, and then you ask all those same teams to cooperate,” observed Panthers President Danny Morrison, a Wofford basketball alum who first met Richardson when the family invited the basketball team for dinner one Thanksgiving break. “There is tension between competing and cooperating. … And it’s all held together by trust.

“Guess why he’s had every important job in the NFL? They trust him. They trust the fact that he really does think in a macro way about what’s best for the NFL.”

Perhaps Richardson’s greatest contribution to the league has been as chair of the stadium committee during a 14-year span in which 25 facilities were built or renovated. Strikingly, he not only advised teams on tactics to get their new stadiums built and paid for, he dove in with both sleeves rolled up, much as he sometimes jumped behind the Hardee’s counter during an unannounced visit.

When Richardson saw that the Bears were at loggerheads on a massive renovation proposal for Soldier Field, he contacted Lester Crown, a civic-minded Chicago billionaire who once sat on his company’s board of directors. Crown introduced Richardson to Chicago Mayor Richard Daley, paving the way for meetings that got the project on track.

“For him to put the time and energy into Chicago, which was almost as great as the time and energy that he put into Charlotte, was really pretty amazing,” Tagliabue said. “But it was a reflection of his attitude that the league is only as strong as its weakest link. What he did there was really amazing and will be an incredible part of his legacy.”

In New York, Richardson faced a different impediment. Because the Giants and Jets were building their stadium as a joint venture, they applied to the league for two bites from the G-3 stadium fund, a low-interest loan pool that was crucial to making the finances work. Many owners initially opposed them, loath to cut a break to two teams in the nation’s largest market.

“There’s no way we would have gotten our stadium deal done without his leadership,” Mara said, “and without him twisting some arms along the way.”

From that sort of wrangling to more subtle contributions — such as getting sunburned at the old stadium in Phoenix to help make the point that the Cardinals badly needed a roof — Richardson treated each project as if it were his own, eschewing phone calls in favor of face-to-face meetings and avoiding emails when given the chance to send succinct handwritten notes.

“We grew up with ‘have good manners and work hard,’” Richardson said, sharing stories in a sitting room at the front of his Charlotte home, where a grandfather clock tolls each hour. “You say you’re going to do something, you do it. Real simple things. My mother said, ‘Go outside. Tell them, my name is Jerry. Let’s be friends.’ Simple stuff. We didn’t have any money. There was no surplus money in my house. None. I didn’t grow up taking vacations, going to the beach, playing golf and tennis. I was working.

“I’m not complaining, though. I was happy.”

A CALM LIFE

A month after his team fell 24-10 to Denver in Super Bowl 50, Richardson flew to New York to convene an annual lunch he hosts for about a dozen NFL operations staffers in appreciation for their work on the game.

When he returned to Charlotte, he was met by four doctors — an orthopedic surgeon, an internist, a kidney specialist and a cardiologist — seated side-by-side in the front parlor of his home.

Last month, Richardson tore his left rotator cuff, the latest in a series of maladies that have beset him in the last two years. His right shoulder also is damaged. He tore his Achilles. He often walks with a cane to keep weight off a knee that should be replaced.

Each of those injuries could be repaired through surgery, but because he’s had a heart transplant and battled kidney disease the risk of infection is great enough that he has opted against it. The meeting with his doctors was to discuss whether it was time to change course.

“I’m consciously trying to re-evaluate and recalibrate how I live my life,” Richardson said. “It’s draining.”

This is striking to hear from a man who followed up a heart transplant in 2009 by negotiating a contentious labor agreement and chasing around the country for the most prudent option to return pro football to Los Angeles.

|

With Rosalind by his side before Super Bowl 50, Richardson seeks a calmer life these days.

Photo by: AP IMAGES

|

But when Richardson describes the months bracketing his transplant, his emotions bubble up, leaving him unable to speak. Facing his own mortality, he was determined not to leave “any potential question marks” to his wife.

When Richardson constructed the organization, he gave each of his two sons their own fiefdom, along with shares in the franchise. Jon was president of the stadium; Mark the team. His daughter, Ashley Richardson Allen, also holds a minority stake.

With his heart failing, Richardson restructured his estate so that there will be no fight over the disposition of the team after he is gone. He also removed his two sons from parallel management positions with the team in 2009, hiring Morrison as their successor.

Richardson knew from conversations with other NFL families that generational transition was often chaotic and could lead to heartbreak. He didn’t want his children quarreling about the franchise, or what to do with it after he was gone.

“You start thinking about, well, I gotta make sure things are right for Roz,” Richardson said. “If there were things in my life that I didn’t want her dealing with, I dealt with them while I could.”

Richardson choked up a few times as he discussed the turns his life has taken since his heart surgeries. Three years ago, Jon Richardson died at age 53 after a long battle with cancer. It is clear Jerry Richardson emerged from all of this with an unavoidably altered perspective.

Meeting with his doctors at his home, he decided to have surgery to repair the rotator cuff. He wants it done in time to conclude his rehab by August, so he and his wife can enjoy the 2016 season.

Richardson once planned a large estate gift to Wofford but instead has opted to donate the money now, while he is here to see the 4,500-seat arena that will bear his name and, even more sweetly, a center for the arts named for Rosalind.

He said he has resigned from all NFL committees but one — the compensation committee, which counts among its responsibilities the determination of the bonus paid annually to the commissioner.

“I’m going to try to live more civil,” Richardson said. “I’ve never lived a calm life. I can’t remember a time — maybe fleeting days — but I’ve never lived what I’d call a giddy life. I’ve never lived a giddy life.

“I don’t think I’m going to live one now. But if there is one, I’d like to try it for a while.”