|

Photo by: TIFFIN WARNOCK / STAFF

|

On a Thursday night in January, the Montcross Chamber of Commerce gathered at a botanical garden outside of Belmont, N.C. More than 200 people turned out from car dealerships and hospitals, fast food franchises and real estate agencies, the natural gas company and the sheriff’s office. They packed the room to hear the town’s favorite son speak.

That’s how they know him around here. Not as Howard Augustine. Not as Humpy. Not even as Mr. Wheeler. But as the Belmont boy done good. The one who went up the road to the speedway north of Charlotte and made a name for himself building a sport with ties to the area as deep as the red clay on which their businesses are built.

They clapped as Wheeler, 73, plodded to the stage. He wore a dark navy suit, red tie and white shirt. Most of his faded blonde hair was parted at the side, but a forgotten chunk jumped off his forehead and pointed at the crowd. He grabbed the microphone and took in the room.

He gives 40 speeches a year to civic groups and feels sorry for the audience at nearly every one. He knows that the food is no good and speakers usually give doctoral dissertations. He wants his crowds to leave saying, “The chicken might be rubber, but at least the speaker was good.” So he started, as always, with a funny story.

“As I was coming over here, driving down I-85 reminded me of this highway patrolman I knew who told me a story. Right after I-85 opened, he said, I was young and trying to give everybody a break. I noticed this car pull onto the interstate. It had absolutely no taillights. So I pulled it over. I felt like I was stopping Archie and Edith Bunker. The guy screams, ‘Why the heck are you stopping me?!?!? I wasn’t speeding! I pay my taxes! Can’t I get on the highway?!?!?’

“It’s night. It’s the interstate. And this is about the most belligerent guy you ever saw. He just kept screamin’ and hollerin’, and Edith goes, ‘I told you to get those taillights fixed six months ago.’ He said, ‘Shut up, woman!’ The patrolman asked to see his license and registration and, of course, like all those, the guy can’t find ’em. He starts screamin’ and hollerin’ again. The patrolman finally looks over there at his wife and says, ‘Ma’am, is he always like this?’ And she says, ‘Only when he’s been drinking.’”

|

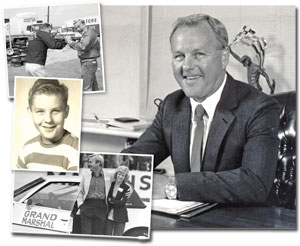

He’s a fighter, he’s a lover (with wife Pat), but as a kid and a young racetrack executive, Wheeler was always a promoter with a big smile.

Photos: COURTESY OF HUMPY WHEELER

|

The room rumbled with laughter. A few people slapped their table, causing silverware to jump and jingle. Wheeler grinned.

Even in retirement, Wheeler remains every bit as deft at captivating an audience as he was during the 33 years he ran Charlotte Motor Speedway. He is still a masterful storyteller with a nose for the outlandish and an eye for the unexpected.

It is those skills that helped him develop some of the most memorable moments in race-day history. There was the Battle of Grenada re-enactment in 1982, complete with helicopters, troops and explosions of balsawood fortifications; a three-ring circus in 1980 that featured trapeze artists, clowns, tigers and elephants; and, perhaps most importantly, the installation of lights in 1992 that resulted in the first night race at a superspeedway.

During his time at Charlotte Motor Speedway, the track swelled from 75,000 seats to 167,000, and though the track’s owner, Bruton Smith, deserves credit for the facility’s physical development, it is Wheeler who deserves credit for filling it. His success in doing so served as proof that sports can be about more than competition. It can also be about the show.

What others are saying

“Before I had to worry about whether the track would be raceable, I enjoyed the prerace show. You never knew what he was going to do, and the unknown caused heartburn.”

■ Mike Helton, president, NASCAR

“At that track, every vendor was given a bag of onions to fry before they opened the gates. You could have had a five-course meal and walked in and been hungry for a burger. Everything was meticulous with him. They’ll never build another Humpy Wheeler.”

■ David Hill, chairman, Fox Sports Media Group

“Some things he did were outlandish, some things didn’t work, but in this business, we often rely on what works and don’t change. He never stopped pushing and trying to be better.”

■ Joie Chitwood III, president, Daytona International Speedway

“He hung a race car from a crane over Interstate 85 one day. People were slowing down to stare at it, and it was blocking up traffic. I called him and said, ‘Humpy, you know you’re going to have to take that thing down.’ He said, ‘Yeah, I know. Sure. I know.’ He took it down and got more publicity when the media talked about us making him take it down.”

■ Scott Padgett, mayor of Concord, N.C.

“He was good at throwing things. When I showed up for work, there were holes in the walls. I said, ‘Why don’t you have this place fixed up around here?’ He said, ‘I’ll tell you later.’ He’d thrown some phones through the walls.”

■ Jim Duncan, former executive vice president of sales and marketing, Charlotte Motor Speedway

“He scheduled the minute-by-minute aspects of the prerace program to bring an audience’s emotion up and down and back up again. They were whipped up to the point where after the national anthem and ‘Gentlemen, start your engines,’ the atmosphere was electric.”

■ Roger Slack, general manager, Eldora Speedway

“Humpy had a pretty low boiling point. You wouldn’t want to test it too much. I can remember going way back before he was president of anything. His father was the athletic director of Belmont Abbey College, where Al McGuire coached. McGuire had a guy from New York he recruited named Danny Boyle who was 6-8. Humpy is 5-8. We were playing touch football, and Danny ran into Humpy harder than Humpy thought he should be run into. Humpy started to slug Danny, but Danny grabbed Humpy’s sweatshirt and pulled it over Humpy’s head. He started spinning Humpy around, and Humpy was throwing haymakers without being able to see.”

■ Max Muhleman, founder, Muhleman Marketing Inc.

“He danced to a different drummer as a kid. He was always looking at different ways to do things. He had quite an imagination. When we played football in the mud, I was always Southern California and he was Notre Dame. He couldn’t just run a bicycle course around the trees; it had to run alongside a railroad [embankment]. There was always a little danger lurking.”

■ David Wheeler, brother

— Compiled by Tripp Mickle

“He didn’t earn the nickname of Barnum and Bailey for nothing,” said NASCAR President Mike Helton. “We had a lot of characters pioneering track development, but as the sport started to explode, Humpy took it to a new level. Other track promoters would look at him and say, ‘I wish I had the moxie to do that.’”

Long before he sold his first ticket to a stock car race, Wheeler began studying what it took to gather an audience. He grew up in Belmont, a textile town of 8,000, and his father, the athletic director at nearby Belmont Abbey College, often took him to games. Wheeler would sit in the stands and imagine what would make the event better, whether it was having music play during breaks in the action or how to butter the popcorn better.

After starting the town’s only bicycle repair shop at 13, he decided to create a bicycle race in hope that kids would wreck their bicycles and hire him for repairs. He wrote articles for the local newspaper and posted fliers around town touting the trophy he’d give the winner of The Great Belmont Bicycle Race. More than a dozen kids showed up for that first race, and he ran races every weekend afterward.

Wheeler’s interest in bicycles morphed into an interest in cars in his teens. It surprised no one in his family when he came home from the University of South Carolina, where he went to play football, and leased Robinwood Speedway, a dirt track 10 miles from the family’s home.

It was there that he first began to push the boundaries of promotion. To drive attendance for a demolition derby, he developed a 10-second TV spot that showed an old Cadillac plunging through the air and smashing five junk cars filled with water barrels. The impact created a massive explosion that sent water spraying everywhere as an announcer said, “Demolition Derby, $2. Kids under 12 free.”

“It was absolute, total mass destruction, and people just loved it,” Wheeler said. “That was one of the best ads I ever had. I was just selling wrecks, you know, because that’s what people wanted to see.”

Wheeler brought his enthusiasm for destruction to Charlotte Motor Speedway in 1975, when Smith hired him to run the speedway. He did anything he could to draw attention to the track.

In 1987, a Hollywood stuntman flew to Charlotte and showed him a painting of the stuntman jumping a school bus the length of a football field. Wheeler hired the daredevil on the spot to do the jump at the speedway before an upcoming race. He took out ads during kids’ programming touting the school bus spectacle and watched as kids and parents filled the track on the day of the race.

The school bus circled the track three or four times, building the audience’s anticipation, and then it rumbled toward a ramp at 75 miles per hour. The ramp catapulted it over a row of junk cars, and it landed on its nose, teetered as though it might flip over, and then slammed down on the cars behind it. After it settled, the driver stepped out of the bus and raised his arms.

“It was so stooopiddd,” Wheeler said, “but the kids went absolutely crazy.”

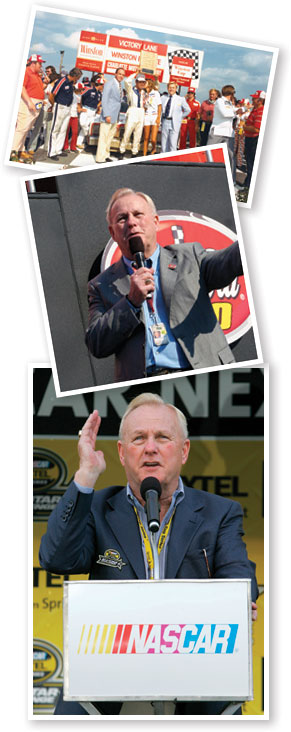

|

Making a circus of race promotion? Wheeler was the ringmaster.

Photos: COURTESY OF HUMPY WHEELER

|

Wheeler’s imagination for the absurd showed no limit during his years in Charlotte. In 1978, he traveled to New York to sell CBS the rights to the World 600 (today’s Coca-Cola 600). During the meeting, the CBS executives said they would only buy the 600 if they got another race, too.

Wheeler threw out the idea of a 300-mile stock car race. They said no. He threw out the idea of a motorcycle race. They said no again. He started trying to think of something that would appeal to them. He was in New York and had taken a cab to the meeting.

“What about the world’s greatest taxi cab race?” Wheeler said. “We’ll get top drivers from New York, Los Angeles, Boston, Chicago and so on, and we’ll bring 20 of them to Charlotte and run them on a special course.”

The CBS executives liked it and bought rights to both races. Wheeler walked out of the room thinking, “How am I going to put this on?”

The resulting race was held on a quarter-mile track that included a tollbooth and a fake hotel lobby where cabs had to stop. On the first lap, three cars ran right through the tollbooth, demolishing it. The hotel lobby didn’t last much longer.

|

Wheeler was the face of the race at Charlotte Motor Speedway, later Lowe’s Motor Speedway, from 1975 until 2008.

Photos: COURTESY OF HUMPY WHEELER (2) / GETTY IMAGES

|

Sports Illustrated called the race sports trash, but Wheeler didn’t care. To him, it helped the sport and raised the profile of the speedway, because the marquee 600 race was televised live for the first time that same year.

But no moment in his career highlighted his ability to dream up and pull off the unexpected more than his last-ditch effort to keep NASCAR’s all-star race in Charlotte.

In 1991, NASCAR’s biggest sponsor, R.J. Reynolds, wanted to relocate the race. The move would cost Charlotte Motor Speedway millions, so Wheeler called RJR’s top sports marketing executive, T. Wayne Robertson, and asked for a meeting. He came armed with a handful of ideas he hoped would convince RJR to keep the race in Charlotte, but none of them resonated with Robertson. Wheeler’s mind raced as the meeting came to a close.

“What if we light the speedway and run the race at night?” Wheeler asked.

Robertson stared at him expressionlessly and asked to be excused for a minute. He left the room and returned five minutes later.

“You’ve got a deal,” he said. “How are you going to light the place?”

“I don’t have a clue,” Wheeler said.

As he walked out of the meeting, he turned to his executive team and said, “Looks like the dog caught the car, boys.”

No superspeedway had lights at the time. No one had even tried to develop a system to make lighting a 2-mile track possible.

|

Top: Wheeler with CMS’s Dan Farrell and Hall of Fame driver Bobby Allison. Above: Wheeler was adept at telling his story to both the fans and the media.

Photo by: COURTESY OF HUMPY WHEELER (2)

|

Wheeler had less than eight months to find a solution. To make matters even more difficult, he insisted there would be no light poles alongside the track cluttering up the infield. He eventually found a company in Iowa that developed a system that used mirrors alongside the track to reflect lights perched high above.

Shortly before the race that May, Wheeler and his daughter, Patti, a TV producer for NASCAR races, were in New York and went to see “Phantom of the Opera.” He was struck by a line in the musical that preceded the score: “Perhaps we can scare away the ghost of so many years ago with a little illumination, gentleman!” He took the concept back with him to Charlotte and wove it into the race program. Shortly before the first lap, the track’s lights dimmed and the in-venue speakers blared, “A little illumination, please.” The lights brightened, and the TV crew showed an image of the track from high overhead.

“It was spectacular,” Patti Wheeler said. “All the ugly parts of the race track were gone. There was just a ribbon of light around the track.”

When Hill met Humpy

Risk-takers bonded over NASCAR and moonshine and have stayed friends

Fox Sports Media Group Chairman David Hill knew nothing about NASCAR in the 1990s, but he was impressed by the sport’s surging ratings and wanted to learn more about it. Everyone he spoke with told him he should go see Humpy Wheeler.

Hill eventually traveled to Charlotte and met Wheeler.

“He introduced me to NASCAR and moonshine in that order,” Hill said.

Hill compared the meeting to a visit to NASCAR’s Hall of Fame. Wheeler told Hill that the sport’s roots ran back to moonshine runners from the North Carolina mountains. Then he pulled a bottle of moonshine from a bar near his desk drawer and offered it to Hill. Wheeler always kept enough moonshine to “indoctrinate people from the far West and the Northeast.”

The two have been close friends ever since.

“We hit it right off because we both came from the same background,” Wheeler said. “He’s Scots-Irish and I’m half. I showed him the town where my mother was brought up, and he said, ‘This is exactly like the town I was brought up in in Australia.’”

Hill said, “He became my mentor in the world of NASCAR.”

At the time they met, Europeans belittled NASCAR because it was a closed circuit style of racing, where drivers only turned left. Hill, an Australian, also struggled to appreciate the sport.

“Humpy explained the difficulty,” Hill said. “There was a guy from Formula One [Alan Jones] who came over to race. He won the race but he came in white-faced and sweaty and said, ‘Oh my God, it was a black out.’ He couldn’t see a thing.”

Wheeler’s children, Patti and Trip, gave Hill his first tour of a race, and Wheeler eventually introduced Hill to NASCAR’s France family. That introduction and Wheeler’s insight into the sport led Fox to pay more than $2 billion in rights fees for NASCAR over the last decade. It’s an investment that Fox supplemented with the acquisition of the all-motorsports channel Speed in 2001.

“There’s almost a direct line for NASCAR on Fox and Speed going back to Humpy Wheeler,” Hill said.

Hill and Wheeler have remained close friends through the years. They share a passion for history, enjoy discussing books and have a mutual interest in the Scots-Irish.

Hill said he admires Wheeler for his “muscular curiosity.” Wheeler said he admires Hill for his creativity and willingness to “wander down the untouched path.”

“We’ve got distinctly different accents, but we’re pretty similar,” Wheeler said.

When Hill comes to Charlotte, he often has dinner at Wheeler’s home. They frequently pull pranks on each other. One time, Wheeler said he sent a police car to pick Hill up at his hotel and bring him to dinner. Hill rode to Wheeler’s house wearing full dress regalia from the Scots Highlands.

“Most friendship in sport is there but it’s pretty shallow, but I find him to be such an interesting person,” Wheeler said.

For Hill, the feeling is mutual.

— Tripp Mickle

Wheeler had an uncanny ability to take ideas to the edge of what was possible. One colleague said that if someone created a spectrum for ideas and put “bland” at one end and “outlandish” at the other, Wheeler would always be pushing employees to get as far from bland as possible.

In 1986, he convened staff to brainstorm the Great American Pep Rally — a prerace event to celebrate buying American products at a time when Japan’s economy was soaring. Staff suggested getting a marching band and the world’s largest American flag. Wheeler’s idea was to shoot a Honda Accord out of a cannon and let it crash and explode on the track. The group ultimately decided that would be in poor taste.

“He was always pushing the envelope,” said Tom Cotter, the speedway’s former director of communications.

Wheeler may have been long on imagination, but he was short on temper. He regularly snapped pencils and threw phones in the presence of employees, and he once threw his fist through NASCAR’s control room tower when the sanctioning body waved a late caution flag in a race. He even threatened to tow NBC’s satellite trucks when the network refused to call the speedway Lowe’s Motor Speedway on air unless the home improvement retailer bought advertising.

Wheeler’s last great promotion may have been his own retirement. He and Smith worked together for 33 years, building not only Charlotte Motor Speedway but also Speedway Motorsports Inc., which they took public in 1995. But their relationship deteriorated over the last decade.

The two disagreed over Smith’s vision for an NHRA drag strip at Charlotte Motor Speedway. Wheeler believed the facility would be a financial loser. Then Smith turned it into a civic headache by threatening to move the speedway if the county blocked construction of the drag strip.

The relationship was strained further when Wheeler came to work one day and saw a new office being constructed for Smith’s son Marcus at the speedway. Wheeler knew Marcus would be taking over soon, but he didn’t know about the construction plans in the facility he was supposedly still running.

Everything came to a head before the 2008 Coca-Cola 600. Wheeler told Smith that he wanted out. Smith asked Wheeler to announce his retirement after the race, but Wheeler, always impulsive and often stubborn, called a press conference the next day. He figured that knowing it was his last race might compel a few more fans to buy tickets.

Smith and Wheeler don’t speak any more, and Smith declined to comment.

“It’s kind of too bad,” Wheeler said. “It’s like Flatt and Scruggs. You know they broke up. There’s no relationship.”

|

When he isn’t promoting his autobiography, Wheeler enjoys spending his time outdoors. He’s learning to ride horses, and he shoots, fishes and flies radio-controlled planes.

Photos: COURTESY OF HUMPY WHEELER (2), TIFFIN WARNOCK / STAFF

|

Wheeler spends half his time today flying radio-controlled planes and learning how to ride horses. The other half is devoted to a consultancy he opened a few years ago, The Wheeler Co. He’s currently advising his son-in-law, Leo Hindery, on the Formula One race Hindery plans to bring to New York-New Jersey in 2014. His remaining promotional energy is channeled into pushing an autobiography he published in 2010.

Selling books is what brought Wheeler to the Montcross Chamber dinner in late January. After telling his joke about Archie and Edith Bunker, Wheeler talked to the business group about how he believed that creativity was the key to solving the country’s economic woes. Wheeler said he had a theory about creativity. He thinks the key is not just having the imagination to dream something up, but also having the ability to recognize someone else’s creative idea.

For that reason, he encouraged employees at the speedway to bring him ideas, and one day, a secretary came by his office carrying The National Enquirer. She laid it on his desk, opened it to the middle section, and said, “This would give kids a reason to come to our Saturday race.” Wheeler looked down and saw a 40-foot stainless steel monster with huge teeth that could eat cars. They called it Robosaurus, and it would grab a car with its hands, lift it to its mouth and chomp the car to bits, sending the wheels and fan belt and engine parts tumbling to the ground below. Then fire would shoot out of its mouth.

Wheeler’s nose for the absurd twitched and his eye for the unexpected bulged. He immediately called the man in California who built Robosaurus and offered him $25,000 to bring it to Charlotte. He held a press conference where Robosaurus split a Chevy Vega in three pieces and dropped them on pit road. Pure culture in America! And when it was over, the operator of the monster stepped out — and it was none other than Dale Earnhardt. The press ate it up.

Wheeler blanketed afternoon and Saturday morning television shows with ads featuring Robosuarus. There wasn’t a kid in the Carolinas who didn’t know that the beast would be eating cars and breathing fire at the next race. The speedway sold 16,000 more tickets than ever before for a Saturday race.

“That’s creativity in action,” Wheeler said.

Wheeler thanked everyone for coming and reminded them that he’d be in the back signing copies of his book afterward. He headed to a table near the front door, pulled out a bag full of Sharpies and planted his elbows in between two stacks of his book, “Growing Up NASCAR: Racing’s Most Outrageous Promoter Tells All.”

Promoter's recipe:

Music, stars, judicious use of explosives

Humpy Wheeler spent more than 33 years running Charlotte Motor Speedway, and his prerace shows became legendary. He hosted three-ring circuses, battle re-enactments, motorcycle stunts and school bus jumps. Over the years, he developed a list of things he believed were critical to a successful promotion. Here they are, in his own words.

1. Blow stuff up. People love to see things get blown up. It goes back to the kid in them. Every video game that sells has someone blown up within 90 seconds, and if that doesn’t happen, the game won’t last 60 seconds in the video business.

2. Pick the right music. Charlotte Motor Speedway held boxing matches before races and even had its own boxer. Every time the speedway’s boxer came out, the PA system blared George Thorogood’s “Bad to the Bone.” People went crazy because they knew he was mean.

3. Find the drama. That’s what I was trying to do with my Cale Yarborough and Darrell Waltrip promotion (in 1978). Yarborough called Waltrip “jaws” in a press conference because he talked so much, so I hung a shark upside down at the track and put a chicken in its mouth to symbolize Yarborough, who drove a car sponsored by a poultry company. A photo of the shark wound up on the AP national wire. I was just trying to piss everybody off and create drama. I did.

4. Bring in celebrities. I once convinced Liz Taylor to come to a race in Charlotte.

|

Wheeler got Elizabeth Taylor to come to the 1977 World 600.

Photos by: COURTESY OF HUMPY WHEELER

|

NASCAR drivers got so popular that you didn’t have to do that anymore, but I don’t care how famous the athletes become. There’s value in fans walking the concourse or sitting in their seats and seeing Jessica Alba or Tommy Lee Jones. It gives them something to tell people about after the race.

5. Embrace the strange. This comes from Bill Veeck. It’s the idea of bringing odd things to the race. I found a man in Arizona who builds three-quarter scale models of cars with a four-cylinder engine. I would give the man gas money to drive the cars to races. You talk about something that will sober a race fan up in a minute. A ’39 four-door Chevy that small driving by will make their chin drop.

— Tripp Mickle