On a hill on the edge of Charlotte sits a 5,000-square-foot building that once served as the office for the first five employees at Hendrick Motorsports. It overlooks a sprawling, 100-acre complex with 13 buildings that serve as the offices for the 550 employees who work for the team today.

|

| Hendrick Motorsports owner Rick Hendrick talks about the next generation of NASCAR owners, the future of teams and how the sport has weathered the recession. |

The difference in size between the initial and current operations at Hendrick Motorsports is indicative of how much NASCAR teams have evolved during the past 30 years. Rick Hendrick opened his first shop in 1983 with an initial investment of $250,000. To start a competitive, single-car team in the Sprint Cup Series today, he would spend a minimum of $40 million.

“The entry-level costs have skyrocketed,” Hendrick said. “I don’t think that’s much different from when I was an original investor in the [NBA’s Charlotte] Hornets. It’s just kind of a sign the times have changed.”

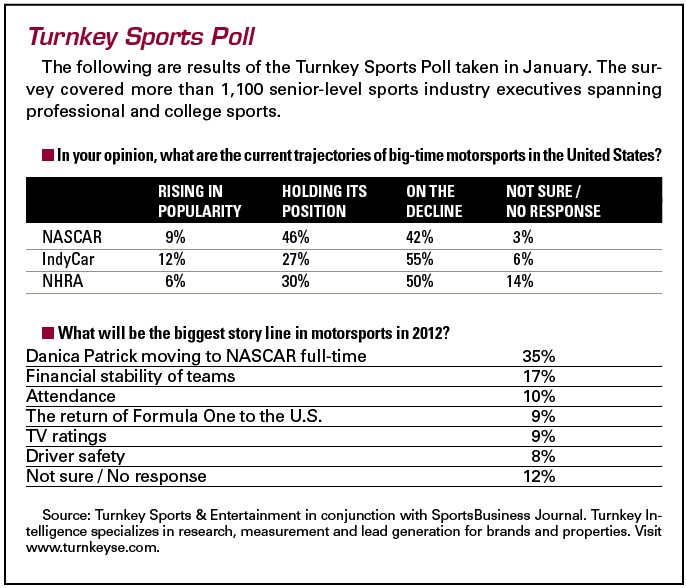

They certainly have. Consolidation, economic challenges and the evolution of multicar teams have condensed a robust group of 37 Cup teams that ran during the 1996 season to the 20 full-time teams that are scheduled to race this year.

The result is a very different ownership field than the one that sustained NASCAR through its first five decades.

Gone are the single-car, family operations. In their place are business enterprises funded by men of means.

The NASCAR industry, which doesn’t have franchises like big league sports operations but depends on independent contractors to develop teams, navigated that evolution without issue. The next transition, however, could prove more challenging.

The sport’s five most successful owners — Richard Childress, Joe Gibbs, Roger Penske, Jack Roush and Hendrick — are all over the age of 60 and acutely aware of the fact that no NASCAR team has successfully outlived its namesake. Four of the five have already developed plans to reverse that trend (Roger Penske was unavailable for this story). Their ability to do so, and the ability of the sport to attract other new owners, will be key to NASCAR’s future.

|

Car owner Jack Roush turned a $5 million investment into a multimillion-dollar operation.

Photo by: GETTY IMAGES

|

“NASCAR would do just fine without Rick, without me, without Joe, without Richard, without Tony [Stewart], without Michael [Waltrip],” Roush said. “They’d be fine without any one of us, but it would be a different landscape without all of us.”

To keep existing teams alive and attract new owners to the sport, current owners say that NASCAR may need to reconsider its business model. Some advocate a franchise model. Others believe the sanctioning body should consider giving teams a guaranteed slice of TV revenue or ticket sales. Either approach would help teams keep pace with rising costs at a time when sponsorships are increasingly difficult to cobble together.

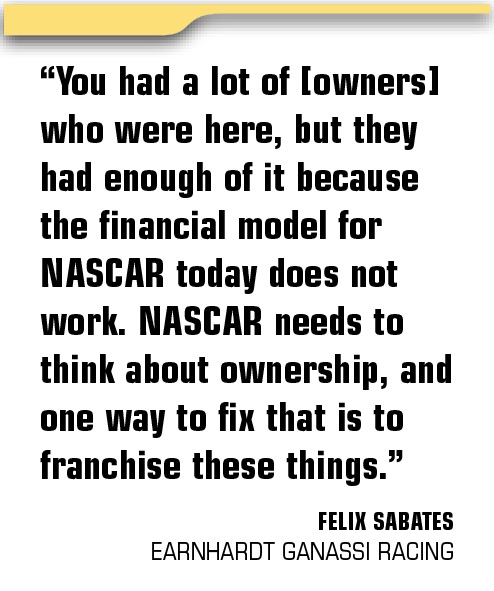

“You had a lot of [owners] who were here, but they had enough of it because the financial model for NASCAR today does not work,” said Felix Sabates, who once owned a team outright for more than a decade but now is a minority owner in Earnhardt Ganassi Racing. “NASCAR needs to think about ownership, and one way to fix that is to franchise these things.”

Rising cost of entry

Seated in a conference room on the second floor of his team’s 83,500-square-foot shop early this month, Roush sounded mystical as he described attending his first NASCAR drivers meeting before a 1987 race in Rockingham, N.C. It was there that former NASCAR head of operations Les Richter gave him an application for the Daytona 500.

“I felt I received something really precious,” Roush said. “They gave me one-forty-third of the … race. They just gave me that.”

Roush, 69, turned that application and his $5 million investment into a multimillion-dollar operation that today includes three Sprint Cup and two Nationwide teams, down from four Cup teams last year. He couldn’t fathom starting from scratch today because the cost is so much greater.

“If I want to have Jack Roush involved in racing for a while I should keep this thing alive,” he said.

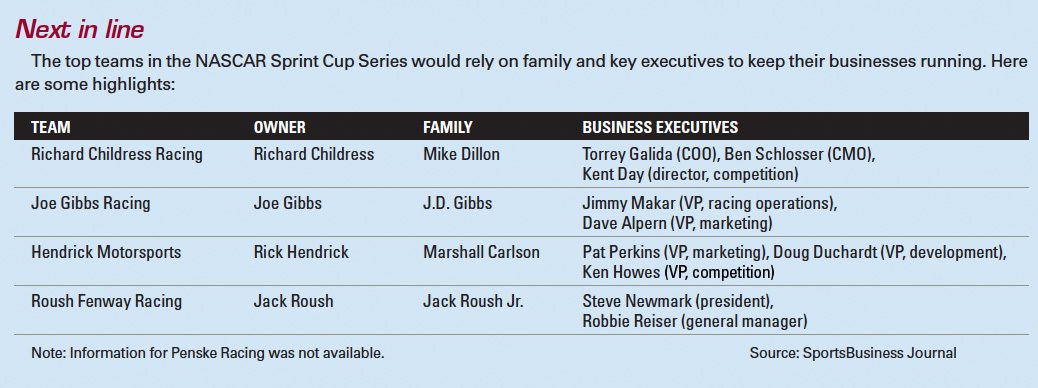

Roush, Hendrick, Childress and Gibbs all began taking steps years ago to make sure their teams would endure. Family is central to each owner’s vision for the future.

|

J.D. Gibbs (left) is waiting in the wings to take over the Joe Gibbs Racing team started by his father.

Photo by: GETTY IMAGES

|

Roush plans to bring his son, Jack Jr., from Michigan to North Carolina in the next three to five years to begin an apprenticeship on running the team. Hendrick, who lost his son Ricky in a plane crash in 2004, eventually plans to turn over operations to his son-in-law, Marshall Carlson. Childress’ son-in-law Mike Dillon and his grandsons, Ty and Austin Dillon, continue to take on expanded roles at Richard Childress Racing. And Gibbs’ son J.D. has worked for their team since its inception, in 1991.

In addition to family, each team has a mix of executives with business and competition expertise who will play a central role in maintaining its existing operations. Roush and Childress also brought on outside investors in Fenway Sports Group and Chartwell Investments, respectively, that can provide a financial safety net if necessary and lend their sports or business expertise to the teams.

“We ran a lot of this by the seat of our pants,” said Childress, 66. “You get a business the size of this business, and it has to be run different than we ran it. They gave us some financial advice and ability to grow the company.”

Since introducing the Chase for the Sprint Cup Championship in 2004, teams owned by Childress, Gibbs, Penske, Roush and Hendrick have accounted for 86 percent of the postseason field and seven of eight eventual champions. Going back even further, since 1990 those owners have accounted for 19 of 22 Cup championships. If one of their teams were to falter, it would reshape the sport.

But longtime sports marketer Max Muhleman, who played a role in bringing Hendrick into the sport, doesn’t believe that will happen. He believes the combination of clear succession plans and stable business operations at each team will allow them to survive long after their namesake is gone.

“These teams are by and large very profitable, as their scale of operation suggests,” Muhleman said. “Profitable businesses are usually going to stay in business through both ownership and management succession.”

Climbing the ladder

When NASCAR head of racing Steve O’Donnell gets asked about what the sport will do if it loses Childress, Gibbs, Penske, Roush and Hendrick, he thinks back to a day in the 1980s when the same questions were asked about Junior Johnson and Bud Moore and takes solace knowing that the sport survived after their teams left.

“It’s so much bigger than four or five owners,” O’Donnell said in a recent conversation about ownership.

But that question today is certainly understandable given the changing context. For most of the 1980s, former team owners Johnson and Moore entered only one full-time car a season, with Johnson having a two-car operation for a few of those years. That meant they accounted for roughly 5 percent, and never more than 10 percent, of any given race field at the time. In NASCAR’s modern era, multicar teams weren’t that common before the 1990s, and the first regular three-car operation was Hendrick’s, in 1987.

|

Rick Hendrick, shown with one of the drivers in his stable, Dale Earnhardt Jr., says he gets calls from all over the world asking about team ownership.

Photo by: GETTY IMAGES

|

Last year, Childress, Gibbs, Penske, Roush and Hendrick combined to field 17 full-season rides, accounting for roughly 40 percent of any given race field. And they won 26 out of 36 Sprint Cup races.

NASCAR, though, takes a different approach to ownership than traditional sports leagues.

Commissioners of most big league sports keep a list of potential owners and regularly meet with interested buyers in case one of their franchises goes on the market, but NASCAR prefers to bring owners into the sport’s lower divisions — the Camping World Truck and Nationwide series — and graduate them to its premiere Sprint Cup Series. It has 175 team owners across the three series.

“For people to migrate up is the best model because they understand the sport better,” O’Donnell said. He pointed to Gene Haas, the wealthy owner of Haas Automation, as an example.

Haas founded Haas Racing CNC in 1999 as a team in a NASCAR regional developmental series and later jumped to Sprint Cup in 2002. In six years, he was winless in 284 Cup races. But things changed for Haas when he was serving a prison sentence for tax fraud and gave driver Tony Stewart an equity stake in the team in 2008. Stewart went on to win the championship last year.

“That’s the goal with any ownership group,” O’Donnell said. “How do we bring you in? How do we create an opportunity to be successful?”

Haas also may have developed a new ownership model for the future of Sprint Cup. In their arrangement, Haas can provide Stewart with the financial wherewithal to underwrite the team, as he did by having his company buy unsold sponsorship on the team’s No. 39 car, and Stewart can provide Haas with a recognizable driver who can attract the sponsors, crew chiefs and employees necessary to build a winning organization.

Michael Waltrip found a similar situation when he sold a stake in his team to Fortress Investment Group director Robert Kauffman. Waltrip started the Cup team in 2007 after years of running a Nationwide Series operation. He blew through millions of dollars and was on the verge of bankruptcy when he found Kauffman. The team stabilized itself, increased its revenue and expanded last year by one car.

“He gave us the ability to invest in the future, to go outside of budget, to improve the cars or our personnel in certain areas,” Waltrip said. “We’ve got a shot now.”

Kauffman said, “People say, ‘Why didn’t you start it yourself?’ The first time I went through the pits with Michael, everyone wants his autograph, and the only person who wants mine is [our chief financial officer].”

But the competitive and financial challenges Haas and Waltrip ran into, respectively, are a testament to the challenges owners often run into as they try to climb NASCAR’s ownership ladder.

Driver-owners hit the wall

On a recent January morning, 22 parking spots outside Kevin Harvick Inc. sat empty. The adjacent two-story tan-colored building still had the KHI logo emblazoned on its door, but the lights were off inside and no one was seated at the reception desk. The place was empty.

During a conversation about the future of ownership nearly a year ago, Hendrick had predicted that former drivers would be the owners of the future. He specifically pointed to driver and Nationwide Series team owner Kevin Harvick as an example. But by the end of the year, Harvick had shuttered his operation.

Harvick, who closed his team in order to focus on winning a Cup championship and begin raising a family, said his team ran at a loss for a couple of years before breaking even. Eventually, though, it became too much effort to continue. “It got to be so big that it just became a lot of work,” he said.

The other driver Hendrick pointed to was Rusty Wallace, who also closed his team later in 2011 because he was struggling to keep up with rising costs. Also, his biggest sponsor, 5-hour Energy, moved up to the Sprint Cup Series this year with another team.

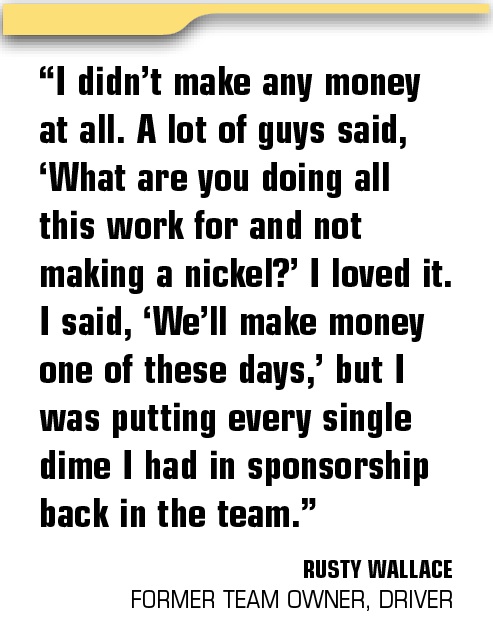

“I didn’t make any money at all,” said Wallace, who put the Nationwide team on hiatus and hopes to restart it soon. “A lot of guys said, ‘What are you doing all this work for and not making a nickel? I loved it. I said, ‘We’ll make money one of these days,’ but I was putting every single dime I had in sponsorship back in the team.”

Both Wallace and Harvick said that they once dreamed of owning a Sprint Cup team, but having owned their own Nationwide team, the only way they would do that is if they partnered with someone with deep pockets as Stewart and Waltrip did.

“I don’t think there’s a driver out there that’s rich enough to say, ‘I want to have a competitive Cup team,’” Harvick said. “You’re going to have to have a Gene Haas. Rick and Richard made a lot of money through the years building a race team, but it’s just not the mode that happens today.”

Hendrick chalked up the struggles of both Harvick and Wallace to the recent recession and said that he and other established owners still get inquiries from all over the world about NASCAR ownership.

“There will always be someone lined up behind us,” Hendrick said. “It’s just been hard to crank up a new team and compete with the large teams that have three or four cars. That maybe has stopped a few new people from coming in. When the economy picks up, I predict there will be new folks that will decide to take a shot at ownership.”

No franchise model

In the 1980s, Childress sat down with Bill France Jr. and Les Richter at Smith & Wollensky in New York. He wanted to sell them on the idea of turning NASCAR teams into franchises. It was a move he believed would make NASCAR stronger and the teams stronger.

Nearly 30 years later, Childress still thinks it would be a good move for the sport because it would give each owner a stake in building the sport, give a value to each of his teams, and maybe even attract new owners to the sport.

Right now, if a team falters, there’s little for them to sell other than used parts, equipment and points that the team earned the prior season. They don’t even own the number on their cars. Those belong to NASCAR.

“NASCAR made a lot of right choices to build the sport to where it is today,” Childress said. “It doesn’t have to be a franchise system. It could be a medallion system like the taxi cabs. Just something to help people that built the sport have a value in this.”

It’s a sentiment many other team owners share. NASCAR teams historically are tougher to sell than stick-and-ball sports teams. The last one that sold, Richard Petty Motorsports, was bought for $12 million, roughly 10 percent of the price George Gillett paid for it just three years earlier.

The RPM team is an example of how the NASCAR landscape is littered with former operations that have either merged with existing teams or closed in recent years. RPM is the result of a merger of three former full-time operations — Yates Racing, Gillett Evernham Motorsports and Petty Enterprises. The Yates team and Gillett Evernham are two of no fewer than 10 full-time Cup operations that have disappeared in the last decade.

Owners point to that as evidence of a need for some mechanism to establish set values for teams.

Because NASCAR teams aren’t franchised, their value doesn’t automatically appreciate over time and they have fewer revenue streams than NBA or NHL teams, which sell tickets, sponsorships and local TV rights. NASCAR teams’ primary revenue comes from sponsorships and purse winnings from races.

There was a time when that was enough for most NASCAR owners. When Steve Germain first sat down and penciled out the numbers for competing in NASCAR in the 1990s, the car dealership owner was surprised by what he saw. There was a chance to make money in the sport.

Nearly a decade later, he said that his family’s truck and Cup series teams still operate in the black but the margins are much slimmer than they were initially.

“It penciled better back then,” Germain said. “It would be nice to know that you own something of value, that when you own the No. 13 in the Sprint Cup Series that it was like having a Toyota franchise.”

O’Donnell said the sport won’t franchise teams any time soon. “We think our model works,” he said. “We’re happy with the structure.”

Bob Jenkins, who owns 127 fast-food restaurants and a Sprint Cup team he founded in 2004, agreed. He said he worries it would hurt the sport by making team ownership more of a business and less of a passion.

“I watch these guys,” Jenkins said, speaking of Hendrick, Penske, Roush and others. “They’re just like me. If I’m running 27th, I’m trying to figure out how to run 26th. I don’t know if you went to a franchise system and could buy a seat at the table you’d have that passion. I just wish there weren’t so many barriers to success.”

Kauffman said that when he first looked at investing in the sport, he was surprised by how difficult the business model was, but he bought into the sport anyway.

“The deal’s the deal,” Kauffman said. “No one forces you to buy or invest in NASCAR. If you don’t like it, just don’t do it.”

But existing owners said there are things the sport could do to make things more attractive to new owners, and easier for existing owners, such as offering a guaranteed share of television or ticket revenue.

NASCAR doesn’t appear intent on making any changes like that in the near future. Instead, O’Donnell said it would continue to try to find ways to encourage owners to reduce costs by doing things like banning testing at tracks.

“We’re not naïve,” O’Donnell said. “There are certainly challenges in the sport, but we’re making sure we put the tools in place for owners to come up through the system.”

Owners say they’re open to cutting costs, but they say when it comes to attracting new owners, that will only make it 50 percent more attractive. It would take guaranteeing revenue or creating franchises or some other creation of value to make the sport twice as appealing.

Until then, they say, NASCAR will be reserved for people who really love the sport and not focused only on the numbers.

“If you’re a purely financial person, I’m not sure you would do this,” Kauffman said. “If you’re doing it for that reason, I don’t think you’re in the right place.”