Less than a month after the Chicago Cubs completed their epic march to the 2016 World Series title, lines of worry already mark the face of Crane Kenney, the club’s president of business operations.

Like all World Series participants, the Cubs are already several weeks behind most of their competition planning for next season. But even more concerning, Kenney knows his ability to build and nurture his staff and sustain a championship culture just took a huge hit. For more than six years, the Cubs’ recruitment pitch was easy — come to Chicago and become part of making history. Now history has been made.

“This is what keeps me up at night now,” Kenney said. “How do we keep motivated? What’s our sales pitch now?”

The victory parade drawing millions to downtown Chicago is barely over. It’ll still be months before the Cubs get their World Series rings. But the moves that Cubs owner Tom Ricketts, Kenney, and the rest of the franchise make to keep that motivation and extend the club’s success will be the next major test in what already has been one of the most remarkable transformations of any major sports franchise in modern history.

|

“To completely rebuild your core product and your entire physical plant at the same time, do it without discounting the price of your product, and go about it without city help, I mean who does that?”

— Crane Kenney

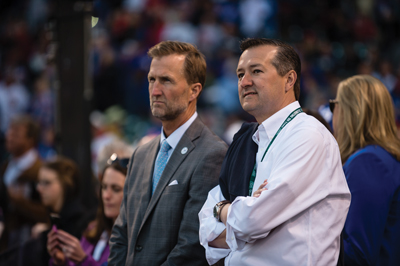

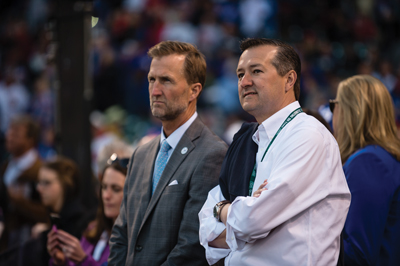

Cubs president of business operations (left) with owner Tom Ricketts

Photo by: GETTY IMAGES

|

It’s easy to focus on last month’s dramatic Game 7 World Series victory over Cleveland, which captivated the country, ended the club’s infamous 108-year championship drought, and drew baseball’s largest TV audience in more than a generation. Or the club’s roster chock-full of young stars, built under the steady hand of Theo Epstein, president of baseball operations.

But the Cubs’ on-field success followed an overhaul in virtually every department and function of the club’s business operations. A patient Ricketts-led plan started with three unyielding goals — winning a World Series, restoring Wrigley Field, and being a strong neighbor and community presence — and then rebuilt nearly everything the club has and does, and in several cases rebuilt it again.

“There was a lot of stuff that had to be fixed. But they rolled up their sleeves, got to work, put a lot of money into this, secured free agents when they felt they were close, and got it done,” said Sal Galatioto, president of Galatioto Sports Partners, which worked with the Ricketts family on the original Cubs purchase from The Tribune Co. in late 2009, and numerous times since then. “This has really become a model for how you rebuild and sustain a competitive franchise across the board.”

Kenney is on the second floor of the club’s temporary Clark Street offices across from Wrigley Field. All around him, even in the relative quiet of baseball’s offseason as another tough Chicago winter approaches, the Wrigleyville neighborhood is alive with noise and construction. The 1060 Project, an ambitious $750 million, privately funded effort involving a hotel, restaurant, new team offices, and other amenities in and around the ballpark, is well underway. Another set of components, including new stadium seating areas, bullpens and a partial remaking of the Wrigley Field exterior facade, is due for completion by the spring.

One of a handful of holdovers from the Cubs’ Tribune Co. era, Kenney is outlining what, all put together, is an almost absurd series of steps Ricketts and the Cubs have taken over the last seven years. Ricketts and his family started by paying $845 million for the club, at the time the highest price ever paid for an MLB franchise, and one that involved a bankruptcy by the Tribune Co. The Cubs moved to not only rehabilitate Wrigley Field, now approaching its 103rd birthday, but also build a new spring training facility in Arizona and a youth academy in the Dominican Republic. And the Epstein-led reconstruction of the roster paralleled a series of often very public and nasty battles the Cubs engaged with the city of Chicago over funding and approvals for the Wrigley Field work, and with local rooftop owners overlooking the ballpark.

“If that was considered for a Harvard Business School case study, it’d probably be rejected,” Kenney said. “They’d see it and think it was too ridiculous. To completely rebuild your core product and your entire physical plant at the same time, do it without discounting the price of your product, and go about it without city help, I mean who does that?”

Lessons learned

The full scope of the Cubs’ rebuild, one Kenney likened to “ripping the franchise all the way down to the studs,” is without a true comparison, but the club still looked all around the sports industry for guidance and ideas. Ricketts, Kenney and other Cubs executives personally toured or studied a variety of facility projects in and frequently out of baseball, including L.A. Live and the Green Bay Packers’ much-celebrated renovation of Lambeau Field, looking at all sort of elements including revenue-generation, use outside of game days, and new ways to showcase franchise history.

The closest thing to a model that the Cubs worked from was in Boston, where John Henry, Tom Werner and their partners led a similar rebuilding of the Red Sox after buying the franchise in early 2002. Henry and Werner inherited a more talented team and their rise to champions just two years later was much quicker, but like the Cubs, the Red Sox needed to breathe new life into a century-old facility, modernize nearly every facet of team operations, and shake off a title drought that had become core to the team’s identity. Both franchises thought of themselves as virtual startups or expansion franchises rather than simply two of baseball’s oldest brands.

|

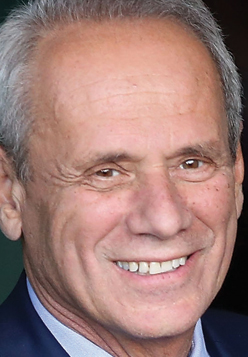

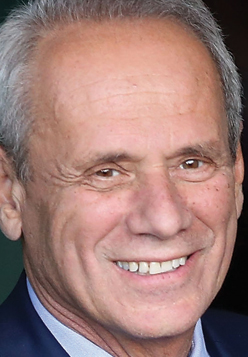

LUCCHINO

|

|

KENNEDY

|

After Ricketts bought the Cubs, he and Kenney spent time with former Red Sox President Larry Lucchino, who played a key role in the Fenway Park rehabilitation. More recently, the interplay has involved owners from both clubs as well as Kenney, Red Sox President Sam Kennedy and Jonathan Gilula, Red Sox executive vice president for business affairs. Many of the conversations of late have focused on incorporating new technology into the ballparks without sacrificing their historical charm, and booking additional non-baseball events.

The Cubs’ 2011 hires of Epstein and general manager Jed Hoyer, who bothworked in Boston under Lucchino, only furthered the ties between the two clubs.

“The Cubs are so analogous to us,” said Kennedy, who toured the 1060 Project work with Gilula while in Chicago last month for MLB owners meetings. “There are a lot of obvious parallels we’ve talked about.”

Personnel matters

The 2009 staff list for the Cubs, the last before the Ricketts purchase, contains a small collection of key names that are still with the club now. In addition to Kenney, Carl Rice is vice president of the Wrigley Field restoration and expansion, and Mike Lufrano is now executive vice president for government and community affairs and the club’s chief legal officer.

|

RICE

|

|

SUGARMAN

|

There was never a mass firing after the Ricketts purchase. Instead, steadily over the course of several years, Kenney rebuilt, enlarged and updated what under the Tribune Co. ownership had been one of MLB’s smallest and most outmoded front offices. To do that, personnel searches frequently veered far outside of baseball, and even beyond sports. Jon Greifenkamp, an early Ricketts-era hire who is now the chief financial officer and senior vice president, came from Thomson Reuters and Price Waterhouse. Alex Sugarman, the Cubs’ senior vice president of strategy and ballpark operations, has an MBA from Columbia and arrived in 2010 after stints with Galatioto Sports Partners and the NHL. Allison Miller, the Cubs’ vice president of marketing, joined in 2012 after holding a series of senior-level roles with General Mills and earning an MBA at Harvard. On and on the list goes.

“I want rock stars working here, and we’ve been fortunate to get them,” Kenney said. “It hasn’t necessarily mattered whether they were in baseball before.”

The new hires, which between 2010 and 2016 more than doubled the business side headcount to 176 employees, arrived with a deep commitment to analytics. It also came with the deliberate creation of a culture in which Ricketts and senior management provided long operational leashes.

“We’re very blessed to have an owner with a very long-term vision,” said Colin Faulkner, Cubs senior vice president of sales and marketing, who arrived in 2010 after working for the Dallas Stars. “[Ricketts] has done a great job giving us the resources we need to do our jobs, and not getting involved in every single decision like you see some other owners do.”

Wally Hayward, who was another key early Ricketts hire as executive vice president and chief sales and marketing officer, said Ricketts’ vision built around team, ballpark and community presence served as a rallying point both internally and externally.

“From their very first press conference, Tom and the Ricketts family had these three very clear goals,” said Hayward, who is now partnered with Ricketts on the W Partners joint venture. “It really worked to get everybody within the organization on the same page right away, and then it was up to all us of us to help bring that dream to life.”

Obstacles

As Kenney is recounting how the Cubs rebuilt the organization under Ricketts and reached their October glory, the emotional scar tissue quickly comes to the surface.

The Ricketts era began with two losing seasons, followed by three more on Epstein’s watch. Off the field, one setback seemed to follow another. An initial effort to secure $200 million in public funding for the Wrigley Field renovations ran into firm opposition from Mayor Rahm Emanuel, leading at one point to a suggestion by Ricketts of moving the club to suburban Rosemont, Ill. The club ultimately funded the renovations privately. But it would still take years for Ricketts to learn the intricacies of Chicago politics, rebuild the relationship with Emanuel, rework the redevelopment plan that would ultimately become the 1060 Project, and secure all the needed public-sector permissions for the effort, complicated in part by the ballpark’s status as a protected local landmark.

|

Theo Epstein handled the on-field aspects of Ricketts’ revival plan.

Photo by: GETTY IMAGES

|

The Cubs and Ricketts, working much of the time out of makeshift offices and trailers, similarly engaged in a years-long battle with rooftop owners, with the issue occasionally reaching local courts. The rooftops issue long rankled Ricketts and Kenney, who believed it amounted to property owners improperly benefiting from the Cubs’ on-field product without making a commensurate investment, even with revenue-sharing agreements dating to the Tribune Co. ownership. The dispute produced plenty of bad local press, which sometimes framed the issue in David vs. Goliath terms and portrayed Ricketts and the Cubs as callous overlords.

Over time, the Ricketts family methodically secured control of the situation by buying up the majority of the rooftops. But Kenney recalls being personally cast as a villain on many occasions. Other initiatives, such as the introduction of Wrigley Field’s first video replay boards last year and Clark the mascot in 2014, similarly generated howls of initial protest. But Ricketts sought to set a tone in which the franchise stayed focused on the long game as opposed to getting caught up in day-to-day dramas.

“For a long while, my Q score locally was really, really bad,” he said. “But that came with the territory. This was a big thing we were trying to do.”

Also helping the Cubs smooth over the bumps was an almost brutal level of candor by Ricketts and senior management. An “Honesty Plan” saw Ricketts, Kenney and other club executives appearing at one town hall after another, filming YouTube videos, and speaking at length each year at the perennially popular Cubs Convention. At each stop, Ricketts repeatedly implored fans, sponsors and anybody else connected with the club to trust the process, even as it took years to materialize in often-painful fashion.

By 2014, Ricketts said of his initial Cubs years, “we didn’t buy the party, we bought the hangover.”

Similarly, team marketing slogans along the way — “Committed,” “Baseball Is Better,” and “When It Happens,” for example — were mere promises of glory to come, and had no illusions of immediate greatness.

“When you can’t sell the baseball on the field, the wins and losses, you have to sell the journey,” Kenney said.

But selling the journey had its issues initially, too. Wrigley Field attendance fell for the first four years of the Ricketts era, and the Cubs were among the first MLB clubs to begin purging their season-ticket rolls of outside broker accounts, shedding more than 1,000 full-season equivalents. The move in the short term cut into ticket revenue, but helped protect the Cubs’ brand on resale markets.

“We asked our fans and our partners to be extraordinarily patient along with us, and thankfully they were,” Faulkner said.

Turning points

There were several key turning points in the Cubs’ franchise rebuild, on and off the field, including the Houston Astros’ decision to pass on third baseman and this year’s National League MVP Kris Bryant with the first pick in the 2013 MLB draft. Or the little-known contractual clause that allowed manager Joe Maddon to opt out of his deal in Tampa Bay and move to Chicago after the 2014 season. Or breaking ground on pieces of the 1060 Project. Or the yearlong 100th anniversary celebration of Wrigley Field in 2014 that served to deepen many fans’ love of the ballpark.

Dan Migala, partner with the Chicago-based Property Consulting Group, recalls a four-game series in August 2015 against the defending champion San Francisco Giants. The Cubs swept the set at Wrigley Field, helping set off a 20-4 run that would catapult the Cubs back into the playoffs for the first time in seven years.

“That to me was sort of the moment of truth where all the promises of the team, and the reality of the business opportunity of the Cubs that had been there all along really began to align, and it’s not really been the same around here since,” said Migala, who has consulted with the club for nearly a year.

|

Ricketts embarked in 2014 on the 1060 Project, which not only expanded and improved Wrigley Field but will also develop land around the ballpark into additions like an office building (under construction above) and a hotel (in rendering below).

Photo by: GETTY IMAGES

|

|

| Rendering: HOTELZACHARY.COM |

Indeed, the reconstruction of the Cubs has generated a marked upswing in the club’s business metrics. There’s of course the current pop for Cubs championship gear in what has become the hottest market in the history of hot merchandise markets, with many licensees struggling to meet demand. Attendance has reversed course, and grown each of the last three seasons, reaching 3.2 million in 2016, and the waiting list for season tickets has surpassed 100,000 names. Season-ticket prices for 2017 are rising by nearly 20 percent after StubHub resale data showed far greater demand for Cubs tickets. Local TV ratings on CSN Chicago grew 41 percent this year, MLB’s second-largest increase.

But others didn’t need to wait until this year, or even last year, to buy into the Cubs’ promise. Since 2013, 10 companies, including Wintrust, Starwood Hotels and Resorts, Anheuser-Busch, Under Armour and the Sloan Valve Co. have signed large-scale sponsorships to become top-tier “legacy partners” of the Cubs.

“The Cubs, from Tom Ricketts on down, took the time to walk us through every piece of their plan, long before we talked about any deal terms,” said Matt Doubleday, Wintrust senior vice president of marketing. The Illinois-based bank two years ago signed a legacy partnership with the Cubs that gives the company branding on top of one of the video boards and naming rights for a Wrigley Field gate, dramatically increasing their relationship with the club. “We knew everything about what they intended with their player development, their property development, and so on. We knew exactly what this could be, and to their credit, they’ve stuck to it and executed.”

The club declined to disclose its annual revenue, but it is believed to be surging toward $400 million, and is up by roughly 80 percent since 2010.

In the meantime, there’s been little time for fun or relaxation in the Cubs’ front offices. In addition to catching up on 2017 business planning, with the title has come a series of new, championship-oriented demands, including developing commemorative books and movies on the World Series run, and creating appearances and tours for the World Series trophy. Kenney fears losing some of his “rock star” team of employees as they seek out new challenges. But in terms of pace, there’s been no slowdown whatsoever.

“It’s just been heads down, full steam ahead around here,” Kenney said. “This is something we’ve already talked to people like the Red Sox and Giants about, all the additional responsibilities that come with a World Series title. It’s obviously great stuff. But since the parade, there’s been maybe two days off around here, including Thanksgiving.”

Soon enough, the calendar will flip to 2017, and next year already means something else in Chicago as the Cubs’ age-old refrain of “wait till next year” takes on a new context.

“It now means something totally different,” Hayward said. “As a lifelong Cubs fan, I can’t wait until next year and getting back there again.”