Editor's note: This story is revised from the print edition.

“I need an integrator,” Dennis Mannion said. “A master integrator.”

On the other end of the phone, Len Perna’s mental Rolodex started spinning.

It was September 2011. Nine months after leaving his position as COO of the Los Angeles Dodgers, Mannion had been hired as president and CEO of the Detroit Pistons. He arrived at the Palace of Auburn Hills to find that, in many ways, time had stopped in 1990.

Sports franchises that win championships tend to keep doing things in the ways that made them successful. That explained why the Pistons’ arena looked much as it had when it opened in 1988, the team’s first championship season, with later titles following in the 1989-90 and 2003-04 seasons. The business side was still arranged in fiefdoms, a relic of an era when marketing and sales staffs didn’t need to talk to each other.

|

Turnkey Search executives meet to discuss candidates for the Pistons opening (clockwise from left): Morgan Lewis, Len Perna, Carolyne Savini, Diana Busino and Bryan Lick.

Photo by: TURNKEY SPORTS & ENTERTAINMENT

|

Mannion has been a creative force throughout a career that has spanned franchises in the four major sports. Before the Dodgers, he had worked for the Phillies, the Avalanche and the Ravens, climbing the ladder. He’d come to believe that integration was vital to generating creative energy — and, from there, the incremental revenue that creates economic success. He had a plan to reorganize the Pistons’ corporate structure, but he needed someone atop each discipline capable of uniting disparate skill sets into a coherent whole.

Someone out there, in professional sports or the world beyond, was just the integrator he sought. But Mannion didn’t have the time, nor the wherewithal, to find that person. And though the process of using a search firm isn’t foolproof, as the recent events at Rutgers have shown, he liked his odds of making the right hire by using one far better than trying to do it alone.

So he called Perna, whose Turnkey Sports & Entertainment is a player in the growing field of sports executive search and recruiting. Mannion had worked with other firms over the years, but none as often as Turnkey. “I like the way Len works,” he said. “I just feel very comfortable with his process.”

The fit between an executive commissioning a search and the recruiter doing it can be as important as the fit between the eventual candidates and the position they’re looking to fill. “If you don’t have the right fit on the front end,” Mannion stressed, “you won’t get it on the back end.”

■ ■ ■

The executive search industry started in the 1950s and came of age on Wall Street in the ’60s. “From there, it spread to the corporate world,” said Bob Beaudine of Eastman & Beaudine, whose father, Frank, was an industry pioneer. Bob Beaudine became one of the first to spin off sports searches.

Beaudine understood that franchise valuations had grown too high for a team executive to simply sift through the stack of résumés that had come in over the transom, or wander down the hall to find someone to promote. What had been a small business with enormous social impact had matured. “The biggest change over the past 20 years is that owners today are already CEOs,” he said. “They’re people who are very successful owning businesses.”

When successful businessmen and entrepreneurs become owners, often by buying out families that may have owned a team for several decades, the best practices of the corporate world usually come with them. That includes executive search. Since investment-banking billionaire Tom Ricketts bought the Chicago Cubs in late 2009, the team has used search firms to fill multiple positions — from a vice president of marketing to a head of human resources — after previously not using them at all under the Tribune Co.

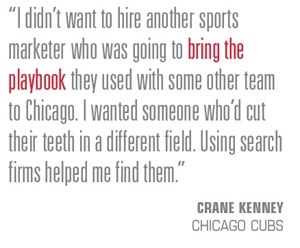

“We’re taking the business from a slow-moving, less-dynamic place under the old ownership to one where we want to innovate and create some new revenue opportunities,” said Crane Kenney, the president of business operations. “I didn’t want to hire another sports marketer who was going to bring the playbook they used with some other team to Chicago. I wanted someone who’d cut their teeth in a different field. Using search firms helped me find them.”

Once a Wall Street lawyer, Perna abandoned that lucrative profession to sell sponsorships for the Detroit Red Wings. Eventually, he started Turnkey with a boost from former Dallas Stars owner Tom Hicks, who wanted an outside firm to help with a renovation project for the University of Texas’ football stadium. “Start a company,” Hicks said to Perna, who was then a Stars employee, “and I’ll be your first client.”

Perna isn’t a former coach or executive. He doesn’t specialize in a sport or a region, though the vast majority of his work comes from pro teams and organizations. He makes some placements of executives responsible for teams and their administration, such as finding Lee Reed as athletic director for Georgetown in 2010. But he gets the bulk of his work by filling the hard-core business positions — from team presidents and CEOs on down.

His point of difference is using the flip side of Turnkey’s business: a market-research arm that works with lower-level employees at pro franchises doing information-gathering projects. In effect, Perna has his research staff working as bird dogs, returning to the office with reports of a marketing innovator here, someone who reimagined sponsorship packaging over there, compiling a talent pool that will be tapped during searches. “If you’re a global search firm that only does CEOs,” he said, “you don’t see the 25- and 30-year-old kids who are doing innovative stuff.”

Mannion had been one of them, staging promotions and fan-friendly exhibits on the Veterans Stadium concourse while working for the Phillies in the 1980s. Later, Perna recruited for him when Mannion was in Colorado and Baltimore. When Turnkey placed Mannion with the Dodgers, Perna did searches for him there. Then the Pistons asked Perna to find them a CEO, and Perna recommended Mannion.

Now, in Detroit, Mannion had hired Turnkey again. He knew he could have done the search on his own; in fact, he was engaged in hiring another executive without a search at the same time. But this job, uniting all information-dissemination under one roof in order to generate what he calls “the energy of mixing,” required a complicated skill set. A rigorous process would help identify candidates who might not be evident on first glance.

Perna had some candidates in mind while still on the phone. But before he could begin, he needed a job description for the new hire. Mannion knew the drill. The four-page document that resulted enumerated both the responsibilities that the new position (tentatively called senior vice president/chief marketing, creative and communications officer) would entail, and — crucially — the skills necessary to succeed at it:

“A creative and compelling story teller with a complete mastery of all messaging, production and distribution techniques … a nimble, forward-thinking executive with a keen sense of programming … an extremely well-prepared, organized, logical, precise, checklist-oriented approach to managing priorities, processes and people.”

The moment that he saw the document, Perna glimpsed success. “We rarely get as clear of a blueprint,” he said. “That’s the key to a successful search.”

Within days, Turnkey established an initial list of 125 candidates. Calls were made to the candidates by Turnkey staff — including a few by Perna himself to candidates he knew well — in an effort to gauge their interest in the position. Over two weeks, the list was reduced to 90, then 60, but then it swelled to 75 as names were added and new leads were explored. Mannion remained blissfully unaware. “He hired us to be a shock absorber,” Perna said.

Three weeks in, on Oct. 11, Turnkey sent a list of 85 potential candidates to the Pistons. Mannion had asked Perna to pay particular attention to candidates outside the NBA and even the major sports. “It’s the maturation of the industry,” Mannion says now. “Upper management brought in from outside sports, maybe with entertainment or the Internet as the connection.”

He trusted that a strong support staff could get an outside hire up to speed on basketball-specific nuances. In addition, revenue from concerts and other non-sports Palace events provides a hefty percentage of the company’s income. Perna listened. Of the 85 candidates on the list, nearly half came from outside sports.

Searches: How much they cost,

how many use them

Typical compensation for a search ranges from as low as $25,000 for some smaller coaching positions to the well-publicized $250,000 that Colorado State paid Jed Hughes and Spencer Stuart in 2011 to find a head football coach. Often, firms receive 20 percent to 25 percent of the annual salary of the position being offered, but that number can be capped or fixed in advance so the firms don’t have a vested interest in recommending more expensive candidates. Other firms are on retainer from franchises, schools or sports-related organizations to handle multiple hires.

After speaking with a range of recruiters and team executives, SportsBusiness Journal estimates that pro franchises hire about a quarter of their top executives using outside search firms, but only about 5 percent of coaches and general managers. College programs use search firms for about half their football and basketball coaching hires and as much as 75 percent of athletic directors, but less than 20 percent for executives below that.

— Bruce Schoenfeld

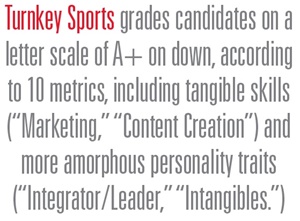

From there, interviews and background checks were conducted by Turnkey’s Carolyne Savini and Morgan Lewis. The candidate list was culled to 36. Those remaining were reinterviewed by Savini and Perna and graded — on a letter scale of A+ on down — according to 10 metrics, including tangible skills (“Marketing,” “Content Creation”) and more amorphous personality traits (“Integrator/Leader,” “Intangibles.”)

What Turnkey didn’t do, as some firms choose to do for high-profile positions, is to hire an outside company to investigate its finalists and identify potential hiring or legal problems. “We typically don’t because we know our candidates — from cradle to grave, so to speak — from when they began as interns on up,” Perna said. “If there had been issues, we’ll know them and disclose them to our clients.”

After interviews and reviews, the highest-scoring 16 candidates were submitted to Mannion as recommended options. On Nov. 11, in a two-hour call, Mannion, Perna and Savini talked through the list. “We gave the color commentary,” Perna said.

The finalists worked in wildly divergent areas. One was a personal publicist. One was an advertising executive. One worked for Disney. One worked for IMG. One had founded a sports service company. Others had spent time with various teams. Their existing compensation levels formed a broad range, too, from $165,000 to $750,000. Though saving $100,000 wouldn’t be the determining factor, salary range did eliminate a potential candidate or two on the top end.

With the information at hand, Mannion decided to interview eight candidates.

Even before his interviews, one candidate stood out. Charlie Metzger had served as the executive vice president for McCann Worldgroup’s Detroit-area office, from which he was running the U.S. Army account. Before that, he’d worked for Allied Domecq as a vice president/group marketing director. He’d also spent eight years as the Miller Lite brand manager, overseeing a $110 million budget that included massive sports buys. Of the outsiders, he was the one closest to the inside. And he was already in Detroit, which meant he didn’t need to be sold on it.

The bad news was that Metzger was up for a significant promotion to run McCann’s Detroit-area office. It was the position he’d been working toward for a decade, the culmination of all his efforts in advertising. He couldn’t imagine turning it down.

Just as Mannion was deciding that he wanted Charlie Metzger, Metzger had come to the decision that he didn’t want the Pistons job.

■ ■ ■

Search firms do more than identify, vet and rank the top candidates for a position. They do more than provide cover for hires, or validate in-house assumptions. Their compensation is often tied to not only finding the top candidate, but actually delivering that person.

Often that’s easy enough. A candidate wouldn’t ask to be considered if he or she didn’t have at least a glimmer of interest, wouldn’t have taken part if most of the parameters weren’t right. “And then you’re gently selling all the way through the process,” said Joe Becher, of London-based Odgers Berndtson, a major international search firm with a thriving sports arm (see related story). “You’re continuing to reinforce why it’s a good career move, why the organization is one you’d want to work for.”

But others participate because they like the ego boost of getting an offer, or to use outside interest to get better pay and benefits from a current employer, or because they’re too polite or humble to decline. That doesn’t always mean they’re ready to make a career change, or move across the country. “We work in an industry where people do have egos and like to be flattered and have their egos stoked,” Becher said. “You have to convince them it’s a meeting worth taking and a job worth looking at.”

That’s when an executive recruiter has to actually recruit. “I love that,” Beaudine said. “The people I try to recommend are the guys who someone says, ‘He’d be great, but you’ll never get him.’ In every search that I do, when you talk to one of those ‘bests,’ those guys you’ll never get, one of them is always willing to listen. It’s the good-looking-girl syndrome: Everyone thinks you could never get him.”

|

Beaudine is a second-generation search specialist.

Photo by: EASTMAN & BEAUDINE

|

Beaudine delivered John Calipari to Kentucky when everyone figured he was anchored in Memphis. He convinced Mike Montgomery to take a job at Cal after he’d had a career across the bay at Stanford. He got June Jones to leave Hawaii and a 12-0 team to come to Dallas and 1-11 SMU. The secret, he said, is selling them on a vision that transcends “more money, more power, more fame.”

“People think that those are the reasons that people change jobs,” he said. “Often, they aren’t.”

Sometimes it’s moving where your family will thrive, or taking a job with better tools — a larger budget, a bigger stadium, a more imaginative boss — that will make success more likely. Jones had been at Hawaii for years; his family was ready to return to the mainland. Dallas is a major market, and SMU hadn’t been to a bowl game since the Pony Express days. “June loves that kind of challenge,” Beaudine said. “That’s the vision that got him.”

Charlie Metzger wasn’t living in Hawaii, but he was making mid-six figures as an advertising executive. He’d been tapped for the leadership position he’d been coveting. He’d let his name be floated by Turnkey because he liked the idea of working in sports. “I was intrigued as a fan,” he said. But once the process became serious, he called Perna and said that the timing wasn’t right. He asked that his name be removed from the list of candidates.

In order to get him to reconsider, Perna knew he’d have to figure out what was missing in Metzger’s life. In Beaudine’s terminology, he needed to find a vision. “He was going to be president of McCann Erickson,” Perna said. “What could I offer him? He knew the area, he knew the Pistons, he understood what the position meant. There was nothing I could tell him about any of that. But there was one aspect of this that he didn’t know.”

Metzger didn’t know Mannion.

Perna believed that any of the finalists would thrive in the position. The difference with Metzger, he realized as the process developed, was that he and Mannion would be wonderfully complementary. They were both unconventional thinkers who looked, sounded and felt like conventional executives. Perna could see them developing a close relationship.

Perna urged Metzger to come to Auburn Hills for an interview. He was local, so there would be no travel involved. “Even if you don’t end up wanting the job, you guys could end up being soulmates,” Perna told him. He was serious. Metzger did his own due diligence and found that Mannion evoked raves from everyone he called. On Nov. 22, Metzger and Mannion met for four hours. “He lit up every room he was in,” Mannion later told Perna. Metzger left feeling excited. For the first time, he could see himself taking the job.

Still, Perna’s work wasn’t done. Recruiters are typically involved until a contract is signed, helping to negotiate salary and benefits. Many don’t get the final piece of their payment until a new hire is in place. Finding the right candidate doesn’t help if the two sides can’t agree on salary, benefits or job description.

Perna had that role here, relaying demands and responses like an international diplomat. The negotiations came down to a signing bonus that Metzger wanted in order to rationalize taking the leap into the unknown. Perna explained that in sports, such bonuses were rare, save for jump shooters, home-run hitters and quarterbacks. “Shift that bonus to the back end, when you’ve proven yourself and they don’t want to let you go,” Perna said, “and I think we’ve got a deal.”

■ ■ ■

More than a year later, Metzger has overseen the evolution of the Pistons’ marketing, communication and informational content. The department-head structure Mannion wanted is working as well as he had fantasized. “It feels like we’re playing in a band,” he said.

For his part, Metzger couldn’t be happier. “The goal isn’t just to get back to the good numbers we had in 2004; it’s a total rethink of sports and entertainment,” he said. “I love it.”

|

Welcome aboard: Dennis Mannion (left), president of the Pistons and Palace Sports & Entertainment, introduces new CMO Charlie Metzger.

Photo by: TURNKEY SPORTS & ENTERTAINMENT

|

Mannion has since hired Turnkey again to fill another executive position. He considered the Metzger hire a home run, but while in the midst of the process, he’d hired a head of revenue without using a search firm. “I didn’t think I needed one,” he said. “It didn’t work. I won’t do that again.”

The practice of paying outside firms to find executives is still far from ubiquitous. Asked about using recruiters, the HR department of MLB’s Los Angeles Angels — a cutting-edge franchise in many ways — responded with an email saying that “finding strong talent isn’t really a challenge for us.” Instead, the team prefers to use internal recommendations and referrals. “Everyone here seems pretty connected,” the email added.

Yet Perna recently received a call that made him sanguine about the future of his profession. The Pittsburgh Steelers, family-owned and traditionally run, wanted him to help find them an executive. “That’s one of the strongest brands in sports, with thousands of résumés of people who would like to work there,” Perna said. “But for the first time, they want a process. More than anything else, that goes to show how times are changing.”

Bruce Schoenfeld is a writer in Colorado.