|

Photo by: TERRY LEFTON / STAFF

|

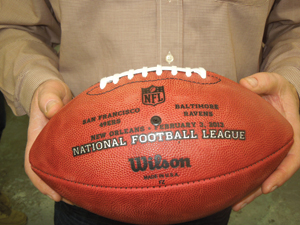

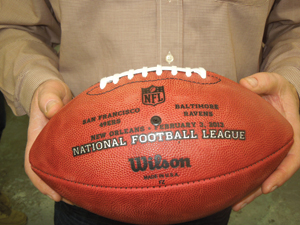

In Ada, Ohio, population 5,947, a small group of fans joined roughly 47 million other people in the U.S. who combined dinner with watching the AFC Championship Game between the Baltimore Ravens and New England Patriots. Ribs, chicken and pizza from Ben Roethlisberger’s nearby hometown of Findlay were served. There was Browns, Packers and Patriots regalia scattered amongst the assembled viewers, but these aren’t just NFL fans, they are fans of the actual footballs on the field.

Welcome to the annual dinner with the most tenured employees at the Wilson Sporting Goods factory in the small town of Ada, where they have made each ball used in every NFL game, including Sunday’s Super Bowl, since 1955.

Since the Super Bowl game balls must have the names of the participating teams on them, the top football artisans in Wilson’s factory, the only remaining domestic manufacturing site for a uniquely American product, gather annually on this night to watch the final championship game before swinging into production. They needed to move quickly, because the Ravens and San Francisco 49ers were scheduled to receive 54 balls each last Tuesday to practice with before the game. Another 54 were shipped the following day. After more than a week of breaking them in, they will turn over half of that lot to the league for use in the game.

Meanwhile, a dozen “K Balls,” for kickoffs and extra points, will be shipped directly to the game’s officiating crew. Then there is the considerable matter of the roughly 10,000 additional Super Bowl

“game balls” with the team names that will be manufactured here over the next few weeks for retail sales and giveaways to Super Bowl VIPs.

“We have competitors who claim they do all the same things, but they don’t have what we have here,” said Kevin Murphy, Wilson’s general manager of football, gesturing toward a factory floor full of equipment manufactured by Wilson for its own use and manned by manufacturers in America’s heartland with an average tenure of more than 20

years. So while New Orleans has the spotlight this week as it hosts its 10th Super Bowl, once Baltimore was through beating New England at roughly 9:45 p.m. on Jan. 20, Ada was the center of the NFL universe, at least for a short while.

“We all get to be part of the biggest sporting event of the year, every year,” said factory manager Dan Riegle, a Wilson employee for 31 years. “That doesn’t get old.”

|

Wilson employees select materials and assemble footballs by hand.

Photos: TERRY LEFTON / STAFF

|

Wilson’s league roots are ancient, at least by NFL standards. Thanks to the lobbying efforts of Bears patriarch George Halas for the fellow Chicago-based company, Wilson has been the league’s official ball since 1941, easily making it the longest-standing licensee. In fact, only eight current NFL franchises predate Wilson’s relationship with the NFL, and while it is difficult to be definitive, many consider the ball manufacturer to be the NFL’s longest-standing business partner.

“It’s all about consistency,” said Riegle, a long-suffering Cleveland Browns fan. “If a guy kicks a record field goal, we want it to be with the same ball as the one that set the [original] record.”

Jane Helser lives three blocks from the factory in Ada and has been sewing here for 47 years. She came to Wilson for a job just after high school because her sister and brother-in-law worked here and she needed more money to support her car payments than her bakery job was providing. After nearly five decades of sewing Wilson footballs, her fingers are slightly twisted and some are bandaged, bringing to mind the gnarled and taped hands of an NFL lineman. When she’s doing her piecework, those hands respond with the precision of a concert pianist, especially when completing the last stitches that close the football. They aren’t all NFL game-quality, but this is a factory that produces more than 700,000 footballs annually and most of them pass through her hands.

|

“There are other jobs in the factory that would be easier, but to me, they would be boring,” said Helser, who had occasion to discuss her craft with NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell, “and it’s still quite an honor to be part of all this.”

■■■

The air is choking with the scent of leather as Riegle leans over around 20 square feet of

hide from cattle in Iowa, Nebraska and Kansas to show where the product starts. “Basically, this is the side of one cow,” he explains. Under ideal circumstances, that “cowside” will yield around 10 Super Bowl game footballs with the suggested retail price of $130 each. The underside of the leather is “shaved,” cut into panels and stamped with, among other things, the names of the competing teams and the commissioner’s signature. A football is composed of four of these panels — two have holes cut in them for the laces. Like most

clothing, football seams need to be on the inside, so the balls are sewn inside out, with the white underbelly of the panels showing until late in the process.

After the panels are sewn together, the embryonic footballs are placed in a “steam box” to soften them. Then, a “turner” performs the delicate and complex procedure of wrestling the football “carcass” right side out onto a metal pole. Now it looks like a football for the first time. A “bladder” — the inside part that is inflated with air — is added and the ball is stitched closed by Helser. Laces are energetically stitched on, and then the balls are put into molds and subjected to 100 pounds of air pressure to assure the proper contour.

The footballs are weighed and inspected for quality control. Employees have developed their instincts enough that they usually can tell

|

At Wilson’s Ada, Ohio, factory, experienced workers such as Jane Helser (second from top) produce more than 700,000 footballs a year. A few of them are shipped out to become Super Bowl game balls.

Photos: TERRY LEFTON / STAFF

|

even without weighing them whether a ball will fit the most exacting standards of a game ball, which must weigh between 14 and 15 ounces. All balls get inspected and weighed. Those with bad seams or ones that are off-weight are thrown in the retail sales bin. Footballs aren’t made one at a time, so it’s tough to say exactly how long it takes to make one, but the best guess within the factory is that a single ball takes between 30 and 40 minutes to complete.

■■■

Wilson’s football business is less than 10 percent of overall revenue for the broad-based sports equipment marketer, but in terms of branding and image, the NFL’s value is incalculable. “The NFL is the most visible and important [property] relationship we have,” Murphy said.

Again this year, Wilson will replicate the production line as part of its presence at the NFL Experience. Even in a digital age, sports fans are inevitably drawn to the authentic, so the sight of Ada’s transported football factory making the ultimate endemic football product usually attracts crowds larger than anything else at the NFL Experience.

|

Wilson will re-create the factory production line as part of its presence at the NFL Experience again this year. It attracts some of the largest crowds at the fan festival.

Photo by: AP IMAGES

|

“Wilson footballs are handmade, and by contract, they have to be made in America,” said NFL consumer products chief Leo Kane. “Those are two things you don’t see much of anymore. And obviously, it’s something at the center of our game from our oldest licensee, so it’s become a real attraction, something fathers show their sons.”

At 11 p.m., less than 90 minutes after the Ravens’ victory, the first football with the names of the competing teams is completed. It’s held aloft with the joy of a newborn being shown off to its family. The Sunday crew cleared out around 12:30 a.m., and the 5 a.m. shift on Monday had the factory going full-bore. Boxes began to fill with footballs for the Ravens and 49ers, which were shipped overnight to the teams.

“Everybody knows the Super Bowl all over the world, and it’s all about the players,” said Helser, wearing a Wilson “More Super Bowl” T-shirt. “We know that, but we also know that if they didn’t have our footballs, they couldn’t play.”