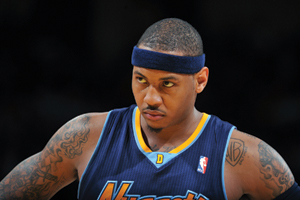

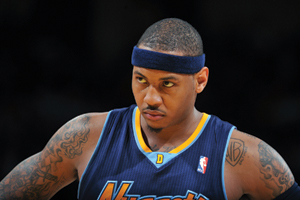

Thursday is the NBA’s trading deadline, and fan websites, blogs and sports radio shows have been abuzz with rumors that superstar Carmelo Anthony of the Denver Nuggets will sign a deal for next season with the New York Knicks. Such a deal would heed Anthony’s professed desire to team with Knicks superstar Amar’e Stoudemire and would revive the offseason chatter about creating a second “dream team” to rival the Miami Heat.

As even those who do not follow basketball know, last summer, superstars LeBron James and Chris Bosh, amid much hoopla, signed with the Heat to join Dwyane Wade in hopes of creating a juggernaut destined for the NBA championship. In the public debate about why the NBA’s top stars are so eager to join forces, however, one factor has been widely overlooked: the impact of the U.S. antitrust and labor laws on the maximum salaries players can earn.

Players in the NBA are subject to a maximum limiting how much they can be paid in any given year (which is distinct from the salary cap limiting each team’s aggregate payroll). Essentially, under the terms of the collective-bargaining agreement between the players union and the owners, each player can earn no more than a fixed sum.

In general, antitrust laws prohibit employers from entering into agreements with one another that place a ceiling on

how much any one of them can pay a key employee, just as they bar businesses from agreeing to fix the price of their products. Such agreements would violate the touchstone antitrust statute, the Sherman Act, which makes “[e]very contract … in restraint of trade or commerce … illegal.” At first glance, it might therefore appear that the ceiling on player salaries is illegal.

|

GETTY IMAGES (2)

Will Carmelo Anthony and Amar’e Stoudemire (top) team up to form the NBA’s next dream team? |

Dating to the Clayton Act of 1914, however, U.S. antitrust law has exempted labor unions from the restrictions on collective action that would otherwise apply. In 1965, invoking a “nonstatutory labor exemption” for the first time, the Supreme Court upheld a rule that prevented any meat seller from operating after 6 p.m., even if no union labor was used, because the rule was the fruit of collective bargaining between the union and the meat sellers’ trade association. In 1987 and again in 1995, relying on the labor exemption, a federal appeals court similarly upheld the team salary cap and other arguably anticompetitive elements of the collective-bargaining agreement between players and owners in the NBA.

The NBA cases did not explicitly address the issue of maximum salaries, but the court’s 1987 opinion specifically stipulated that the college player that brought the suit, who rejected an offer from the team that drafted him, would have been offered a higher salary if not for the team salary cap and the other terms of the CBA. Nevertheless, the court said, if it were to rule in favor of the player (who, ironically, is now an NBA referee), “federal labor policy would essentially collapse.” The court, in short, made clear that the shield guarding collective bargaining from antitrust scrutiny is thick and wide.

Protected by this shield, team owners have continued to negotiate for and obtain caps on both individual salaries and team payroll. For superstars capable of commanding maximum salaries like Anthony and Stoudemire, the effect of these caps is to prevent them from auctioning their services to the highest bidder. Because any team wanting to sign these players will have to pay the maximum, the caps effectively remove salary as a consideration in determining where these superstars will play. Even though the media coverage last summer played up James and Bosh’s desire to join Wade in Miami and to win a championship, the odds are good that, but for the courts’ expansive interpretation of the labor exemption to the antitrust rules, these players would be playing for the teams that paid them the most money.

A comparison to baseball allows us to speculate on the effect that the maximum salary has on the compensation of athletes like these. In baseball, which has no salary cap or maximum salary, players earn whatever they can command in an open and relatively unrestricted market. Alex Rodriguez, baseball’s most highly paid athlete, earns an average of $27.5 million per year based on his latest contract with the New York Yankees. That is approximately 50 percent more than what NBA athletes receive if they are paid the maximum salary.

The situation is full of irony. The labor exemption, originally intended to protect the bargaining position of labor unions and their members, now limits the opportunity of some employee-athletes to get paid what they could command in a fully competitive market. Meanwhile, the salary restrictions, originally promoted as a means to preserve competitive balance, make it possible for superstars to join forces on powerhouse dream teams.

Setting aside their slow start in the first month or so of the season, the Heat has a better record than any team this year other than the San Antonio Spurs. With the existing CBA expiring at the end of this season, it will be interesting to see whether the Heat’s success, combined with the possibility of another dream team anchored by Anthony and Stoudemire, will lead to modifications in the existing salary restrictions when a new CBA is negotiated.�0;8;

Jerome S. Fortinsky (jfortinsky@shearman.com) is a litigation partner and David Hambrick (david.hambrick@shearman.com) is a litigation associate at Shearman & Sterling LLP in New York.